Sort by Category

Know The Member - Cindy Ruskin

Get to know our members!

Cindy Ruskin - Oil painter and mixed media artist

Get To Know The New Shul Member: Cindy Ruskin, Oil painter and mixed media artist

New York City artist Cindy Ruskin works in a variety of forms including oil painting, gold leaf, encaustics, animation, book arts, and collage. In 2006 she had a solo exhibition at the Matthew Marks Gallery in Chelsea, NYC, to benefit the Duk Lost Boys Clinic in Sudan. Her works have been included in New York City exhibits at Lincoln Center, the Center for Book Arts, Umbrella Arts Gallery, the Pen and Brush Gallery, and at the California Museum in Santa Rosa.

After growing up in South Africa, Cindy moved to the U.S. where she received a BA in art history from Harvard, specializing in historic materials and methods -- while also working on stage sets and animated films. Later, Cindy took art classes at the San Francisco Art Institute, California College of Arts and Crafts, the S.F. Art Academy, New York's Center for Book Arts, and the Art Students League.

With the goal of using art to teach and build community, Cindy has worked on several projects with the low-income children in New York City. She created a mosaic for the the women's room on the first floor of the Lower Eastside Girls Club. She was the art director of Lower East Side Bike Parade where she ran workshops, helping neighborhood kids decorate their bicycles. Since 1999, she has run the art program at Avenues for Justice, an alternative to prison program for juvenile offenders. She also taught art at the Lower Eastside Girls Club and volunteered in New York public schools, teaching art history and giving museum tours.

Cindy wrote the 1998 book, The Quilt: Stories from the Names Project, which was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize, and she co-wrote the Academy-Award-winning HBO documentary, COMMON THREADS: Stories from the Quilt.

To find out about Cindy's latest works, follow her on Instagram: @cindyruskin_fineart OR on her website: www.cindyruskin.com

Hanukkah Preschool Program

Yonatan Gutfeld’s preschool program at the Y.

Some magical moments of our Music Director, Yonatan Gutfeld’s preschool Hanukkah program at the 14th street Y last December.

The Great Crocodile

by Rabbi Misha

Kabbalistic wisdom on God, good and evil for the week of January 6th.

Dear friends,

Imagine yourself being invited into the unknown by some gentle voice. Imagine that what you hear in that voice is the voice of your beloved, or maybe your mother, someone you trust beyond everyone else. They take your hand and walk you into one room, then another, each room going deeper and deeper into some beautiful, majestic home. After many wonderous rooms you enter the largest one yet. A few stairways spiral upward, all leading to the same place, the seat of The Great Crocodile.

This is the Zohar’s depiction of the first verse of this week’s Parasha, Bo:

God said to Moses: Come to Pharaoh.

When Moses, with the Holy One’s gentle guidance, arrives at these stairways, he understands a few things: The creature at the top is an expression of Pharaoh. The crocodile is divine, a feature of God. Moses can see that Pharaoh and everything he represents is מִשְׁתָּרִשׁ בְּשָׁרָשִׁין עִלָּאִין, rooted in the high realms. He also knows that he is supposed to walk up those stairs and confront this crocodile. But he won’t. He is too scared, paralyzed by the ramifications of what he has seen.

The Zohar is neither scared nor paralyzed. It isn’t interested in a comfortable notion of divinity, or a neat and pleasant idea of good and evil. It isn’t looking for the Torah to be clear-cut and self-affirming. It is actively seeking out the challenge to its own ideas of right and wrong. It’s not only Pharaoh and the Egyptians who thinks he is a god, but Moses and the Jews can see the truth in that too. Moses enters into God and finds Pharaoh there.

God, like us, is not only good. I’ll repeat that. God is not only good. Godliness is inclusive of every aspect of existence, every possibility of our imagination, every dark wish. Every lie exists therein. Every selfish act, every expression of chaos, every tweet and every feeling of despair; everything is included in God. How could it not be, in a system in which God is understood to be the creator of everything, the life-source and death-source in whose image we live?

What you hate is part of you.

Who you blame is inside of you.

Your oppressor is not absent in your oppressed self, nor even in your liberated self.

Acceptance of reality is important. Without it we are shooting in the dark, or groundlessly dreaming. The Great Crocodile can be a beautiful teacher.

“The mystery of the wisdom of ‘The Great Crocodile hanging out in his river’ has been demonstrated to those seekers who know the mysteries of their God,” says Rabbi Shimon in the Zohar.

And yet, this does not mean that we are supposed to accept reality quietly. The lesson may well be about when to confront the earthly expressions of the crocodile, and how to beat and subdue it.

When Moses is standing there frozen in fear of the reality he has just learned, God steps in.

“When the blessed Holy One saw that Moses was afraid, He said to (the crocodile) ‘I am against you, Pharaoh king of Egypt, the Great Crocodile hanging out in his river…’ The blessed Holy one, and no one else, had to wage war against him…”

God must wage war against pieces of God’s-self, and so must we. This is true on a personal level, a societal level and a global level.

This evening we will have a special Shabbat, in which Rabbi Jim Ponet and New Shul co-founder Ellen Gould will help us think and sing through what we have to learn from, and how we can confront and subdue The Great Crocodile, on the week of the anniversary of the insurrection.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Moments

by Rabbi Misha

A year is made up lots of little moments.

Dear friends,

As the year comes to close I find myself thinking back to the smaller moments that have constituted the vast majority of 2021. These were of course in certain ways colored by the bigger events. Biden came into office, the vaccine rollout, waves of the pandemic, the constant knowledge that people are sick and that many are dying. 100 shades of confusion as to how to act and when to act differently and what each different stage and new bit of information means or doesn’t mean. There were big changes in peoples personal lives as well. Changing work situations, adapting to new stages of life, health issues that have come and gone, happy occasions and trying occasions and sad occasions.

Between each of those there was a lot of living. A lot of doing the things of the every day, surrounded by the people who we are used to seeing. There were meals, and movies, and walks, And doing nothings. There were moments of thinking, talking and reading. So much of the time we spent was good. Even when overall many of us experienced difficult times.

In this weeks Parasha Moses asks god a question:

למה הרעות לעם הזה?

Why did you make things so bad for the people?

The people are in a tough spot. They’ve been slaves for a long time. Pharaoh’s been tightening the grip, and when Moses shows up and convinces them it’s time to stand up and get free, pharaoh responds with even more hardship. It seemed as though redemption was at hand, but instead it’s taken them backwards. That’s when Moses asks his question.

Why did you make things so bad for the people?

God gives a strange answer.

”I appeared to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob as El Shaddai, but I did not make Myself known to them by My name יהוה.”

Until now, says God, I’ve appeared as the god Shaddai. Now I am making my first appearance to you and the rest of the people for the first time as YHVH, or Adonai. Shaddai derives from the Hebrew word for a woman’s breast, Shad, and therefore carries with it a strong maternal connotation. It’s as if until now God was mothering the people, caring for them like one does for a baby, protecting them, feeding them. Now, as the nation grows up God manifests as the strange, past-present-future of the verb To be. The story of redemption, of moving to the next stage in life, is composed of infinite moments of being. Some large moments, some incredible moments, some terrifying moments, and mostly lots and lots of little moments in which to be.

The Hebrew word for moment, rega, is where the root for the word for calm, ragua comes from. To be calm is to embody the moment, to be “momented.” I wish us all a year filled with countless moments of calm that come together like a puzzle to form the next step on our path out of the narrows to ever expanding freedom. May we manage to enjoy the moments as they come, to think back to the sweet moments that we experienced this last year, and to create a time of healing and freedom for all.

Happy 2022!

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Practicing Lightness

by Rabbi Misha

Days like these demand a light state of being if we do not want to fall into despair, anger and depression.

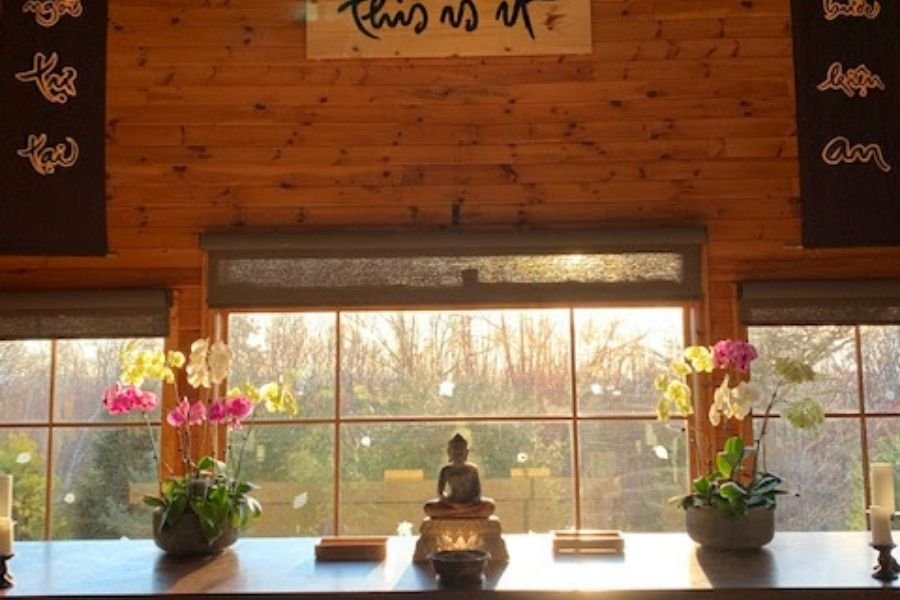

Blue Cliff Monastery

Dear friends,

Lightness is not a state of being that the Jewish tradition tends to espouse. Ours leans towards the weighty, the digging into concepts complicated and deep, toward responsibilities placed on our shoulders for the sake of preserving our tradition, healing the world and doing what we were placed on this planet to do. The Hebrew word for light (the opposite of heavy), Kal, appears a whopping zero times in the Torah. The few times in which the verb using the three-letter root of Kal appears in Torah are anything but light. Sarah feels like she has “become light” in the eyes of Hagar, meaning she doesn’t respect her enough. Children who “mekalel” their parents, understood as curse but literarily lighten, are to be put to death. Moses offers us “the blessing or the curse,” the brachah or the klalah, the latter also deriving from the same root, ק-ל-ל.

But days like we are experiencing lately demand a light state of being if we do not want to fall into despair, anger and depression.

I was reminded this week of the deep sense of gratitude I had toward Quentin Tarantino after I watched Inglorious Bastards. This Holocaust revenge movie could have never been made by a Jew. We needed a friend to come and make it for us. Another friend showed up for me to help me lighten my attitude.

“We need to cultivate a spiritual dimension of our life if we want to be light, free and truly at ease,” writes the Vietnamese Buddhist teacher Thich Nhat Hanh. “We need to practice in order to restore spaciousness.”

I had the wonderful opportunity to spend a couple days at one his followers’ monasteries last week, Blue Cliff Monastery in the Catskills. It gave me an opportunity to practice this light spaciousness, as well as find some tools to retain a degree of lightness after I came back. Since returning several things have happened that would normally leave me feeling heavy and miserable: Omicron exploded, my son got sick, all my kids stayed home from school for a week and we had to cancel our family holiday plans. Throughout this time, my mind and heart have fared far better than usual thanks to Thich Nhat Hanh’s teaching on the practice of lightness.

What has this practice consisted of?

A few minutes of meditation in the morning, a few minutes of washing the dishes (especially pots and pans, which I usually hate washing) in the afternoon, and a few minutes of playing with my kids in the evening. During each of these events, in place of my habitual attempt to finish these tasks so I can get to the real thing I want (AKA “need”) to do, I make an effort to simply breathe, relax, and enjoy what I’m doing. Breathing, I’m finding, can be an enjoyable activity.

It’s not always simple, of course. But the experience of carrying the world on your shoulders, of weight and noise and mayhem, of the disaster inherent in not accomplishing this or that task, is often just an experience. We can work on disassociating ourselves from that weight.

The truth is that our tradition does teach these lessons as well. The psalmist wrote:

שויתי יהוה לנגדי תמיד

I see YHVH in front of me always.

YHVH, of course simply means being.

In whatever we do, we can try to keep the present moment in front of our eyes, rather than everything that isn’t there. We can ask ourselves: where in our lives are we being unnecessarily heavy? What are we experiencing as weight, which in our moment-by-moment reality has no actual existence?

In our Saturday morning prayers we find the Hebrew word for light denoting a desirable state of mind, which opens up the door to gratitude. I will leave you with the words of Ilu Finu, and wish you a Shabbat of lightness, spaciousness and ease, and a sweet birthday of our friend Jesus Christ:

Were our mouths as full of song as the sea,

and our tongues as full of melodies

as its multitude of waves,

and our lips as full of praise

as the breadth of the heavens,

and our eyes as brilliant as the sun and the moon, and our hands as outspread as the eagles in the sky ---

and our feet as light as gazelles’

Even then we would be able to thank you only for one millionth of a millionth of the blessings we live with every day.

אִלּוּ פִינוּ מָלֵא שִׁירָה

כַּיָּם וּלְשׁוֹנֵנוּ רִנָּה כַּהֲמוֹן גַּלָּיו

וְשִׂפְתוֹתֵינוּ שֶׁבַח כְּמֶרְחֲבֵי רָקִיעַ

וְעֵינֵינוּ מְאִירוֹת כַּשֶּׁמֶשׁ וְכַיָּרֵחַ

וְיָדֵינוּ פְרוּשׂוֹת כְּנִשְׂרֵי שָׁמַיִם

וְרַגְלֵינוּ קַלּוֹת כָּאַיָּלוֹת:

אֵין אָנוּ מַסְפִּיקִים לְהוֹדוֹת לְךָ

יְהֹוָה אֱלֹהֵינוּ וֵאלֹהֵי אֲבוֹתֵינוּ

וּלְבָרֵךְ אֶת־שְׁמֶךָ עַל־אַחַת

מֵאֶלֶף אַלְפֵי אֲלָפִים

וְרִבֵּי רְבָבוֹת פְּעָמִים

הַטּוֹבוֹת נִסִּים וְנִפְלָאוֹת

שֶׁעָשִׂיתָ עִמָּנוּ וְעִם־אֲבוֹתֵינוּ מִלְּפָנִים:

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

No Rewards Please

by Rabbi Misha

One of the most helpful concepts Jews have come up with, and one of the hardest to accomplish is called “Lishma”

Dear friends,

During the 7+ years I was studying toward ordination people would often ask me “what are you going to do once you’re ordained?” I consistently had no answer. I didn’t know what I wanted to do as a rabbi. I barely understood why I was doing it in the first place, other than some internal pull met with some external encouragement. I knew I was in it, and doing it and that it was important to me to complete it and to do it right. It was one of the few things in my life thus far that I managed to do without giving too much thought to what I will get out of it or what purpose it will serve. That kept the process both fresh and edgy and allowed me to reach the ordination ceremony open to what might come. A few months later I was rewarded with the wonderful opportunity to jump on this sweet, curious looking boat called The New Shul.

One of the most helpful concepts Jews have come up with, and one of the hardest to accomplish is called “Lishma,” or “for its own sake.”

Maimonides wrote in Mishneh Torah:

Let no man say: "Behold, I perform the commandments of the Torah, and engage myself in its wisdom so that I will receive all the blessings described therein, or so that I will merit the life in the World to Come; and I will separate myself from the transgressions against which the Torah gave warning so that I will escape the curses described therein, or so that I will suffer excision from the life in the World to Come". It is improper to serve the Lord in such way, for whosoever serves the Lord in such way, is a worshiper because of fear, which is neither the degree of the prophets nor the degree of the sages. And the Lord should not be worshiped that way.

Torah, to Maimonides was far larger than just the commandments. To the rabbis in Talmudic times Everything we do is Torah, from the loftiest study to the way they used the restroom. Maimonides may be focusing on Torah, but his words apply to almost everything we do. If there is too strong a utilitarian aspect in most things we do, if we are too often trying to extract things out of our actions we may, from this vantage point, have a problem. Any action that is performed in an attempt to squeeze something out of it for your benefit is not an action done “lishma.” The capitalist system, and the American reality both lead us toward utilization rather than to a quieter type of “being with” what we are doing.

Personally, I find myself constantly trying to accomplish tasks. Be they work or house or family related, so much of what I do is an attempt to complete the things that I believe need to be done. Even in the category of gaining knowledge, or creativity, or experience, I can fall into the habit of “accomplishing things,”rather than doing them for the sake of doing them. I might read a book for the sake of completing all of a certain writer’s work. I might study Talmud for the purpose of finding a particular piece of information, or read the Parasha in order to have what to write to you on Friday. I might practice my musical instruments so that I can bring in a song to Shabbat. Even the articles I choose to read in the publications I choose to follow are often chosen simply for the sake of re-enforcing my opinions. Confirmation bias is a good example of not “lishma.”

In a way there’s nothing wrong with any of those examples. Certainly judging ourselves isn’t helpful. Sometimes, as was coined in the Talmud: מתוך שלא לשמה בא לשמה

“Out of not lishma comes lishma,” or: out of doing something not for its own sake one learns to do it for its own sake. True though that may be, our countless actions done not “Lishma” often feel deeply misguided.

We need to work on releasing the utilitarian aspect of as many of our actions as we can, and simply doing them for the sake of doing them. When we manage to do that, often rewards come of their own accord. When you manage to be there with another person without an agenda, often the depth of communication is deeply enhanced. In study I often find that the deeper realms reveal themselves as soon as I manage to let go of my pre-conceived ideas of what will happen in the study session.

In the Mishna we find the following description:

Rabbi Meir said: Whoever occupies himself with the Torah for its own sake, merits many things; not only that but he is worth the whole world. He is called beloved friend; one that loves God; one that loves humankind; one that gladdens God; one that gladdens humankind. And the Torah clothes him in humility and reverence, and equips him to be righteous, pious, upright and trustworthy; it keeps him far from sin, and brings him near to merit. To him are revealed the secrets of the Torah, and he is made as an ever-flowing spring, and like a stream that never ceases. And he becomes modest, long-suffering and forgiving of insult. And it magnifies him and exalts him over everything.

Seeking rewards, says Rabbi Meir, prevents you from reaping them. Not seeking them showers you with countless rewards.

Singing is one of the hardest things to do not “lishma.” It is often a moment of freedom from our capitalist way of life. Music can help us treat our actions with more presence, intention and softness; To open us up to the unexpected. That’s why we will be devoting our Kabbalat Shabbat this evening to music and song as we look to welcome Shabbat “lishma.”

I hope to sing with you this evening at 6:30pm at the 14th Street Y, or on Zoom with our musical guests cantor and singer Raechel Rosen, and percussionist Yuval Lion.

Shabbat's Zoom Link here.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Choreography of Nearness

by Rabbi Misha

One of my closest childhood friends became very religious when we were 16. Over the course of a year or two he transitioned from being the kid that introduces cheeseburgers to his slightly more traditional Jewish friends, to a bearded aspiring rabbi.

Dear friends,

One of my closest childhood friends became very religious when we were 16. Over the course of a year or two he transitioned from being the kid that introduces cheeseburgers to his slightly more traditional Jewish friends, to a bearded aspiring rabbi. A year ago I asked Reb Leibush, now the head of a yeshiva in Jerusalem what sparked that transition. He answered like he answered me decades ago. He took three steps back before praying the Amidah, then three steps forward. During the time of that not very long prayer, before he concluded with three more steps back, bowing all around and two steps forward, something happened to him that he couldn’t ignore, nor define, but he knew that his life had changed.

The Amidah, our central prayer of request, our longest moment of silence, our standing time when our feet are fixed in place, this is our most intimate moment with God (or ourselves) in our prayers. There are physical preparations for this prayer as well as mental ones prescribed. Mental prep includes prayers of praise and gratitude, assertions of our world view and the limits of our knowledge, songs, devotional poems. Then come the physical actions: we turn our bodies toward Jerusalem, we take three steps back and three steps forward, and begin.

The strange magic of these dance moves, choreographed by rabbis for us thousands of years ago is illuminated in this week’s Parasha, Vayigash.

We find ourselves in the climax of the Joseph saga. He’s already been sold to slavery by his brothers, taken to Egypt, imprisoned unjustly, and used his understanding of dreams to become Pharaoh’s right hand man. He has saved Egypt from a terrible famine, and has already given food to his brothers, who have come from Canaan looking to stave off starvation. He hasn’t revealed himself to them though he certainly recognizes them. The second time the brothers come back after the food Joseph gave them has run out he devises a trick that puts his one full blood brother, Benjamin in prison. The defacto leader of the brothers, Yehudah now must respond.

וַיִּגַּ֨שׁ אֵלָ֜יו יְהוּדָ֗ה

And Judah approached him

This approach, the title of the parasha, is one of the three sources that inspired our pre-Amidah choreography:

The reason (for taking three steps before the Amidah) is because there are three “approaches” in prayer (found in Tanach): “And Avraham approached,” “And Yehudah approached,” “and Eliyahu approached.”

(Rabbi Avraham Eliezer bar Isaac)

The three instances where the word “Vayigash”, “and he approached” appear in the bible are followed by deep, honest expressions of a major need.

Rabbi Moshe Iserles writes:

“When a person is about to pray [the Amidah], he should take three steps forward, like someone approaching and drawing near to something that must be done.”

Yehudah had no choice. He had to get his brother out of prison or his father would have died of sorrow. And he will express this in clear language to this Egyptian ruler who he does not know is his brother. But before any words are said, he must first move his body nearer to him.

It is the silent physical movement that first grabs Joseph’s attention, signaling to him that something is about to happen. When we speak to our loved ones often a similar takes place. A physical movement away from them can signal fear, lack of clarity or care or love or importance. A movement toward them can signal a desire to engage, your need of your loved one and clarity of intention. It cries out: “I want to be close to you,” which can often be more effective than words.

In order to draw near, to come close, we must approach. This is the first lesson the rabbis learn from this moment of high drama and tension. Then come his words, ending with a selfless act of sacrifice:

Please let your servant remain as a slave to my lord instead of the boy (Benjamin), and let the boy go back with his brothers. For how can I go back to my father unless the boy is with me? Let me not be witness to the woe that would overtake my father!”

When we approach God or anyone else in this way, drawing near with selfless love of others, even if we have harmed them or done wrong, the response suggested in this story is a breaking down of barriers, inhibitions and anger into total and complete forgiveness:

Joseph could no longer control himself before all his attendants, and he cried out, “Have everyone withdraw from me!” So there was no one else about when Joseph made himself known to his brothers.

His sobs were so loud that the Egyptians could hear, and so the news reached Pharaoh’s palace.

Joseph said to his brothers “I am your brother Joseph, he whom you sold into Egypt.

Now, do not be distressed or reproach yourselves because you sold me hither; it was to save life that God sent me ahead of you... it was not you who sent me here, but God;

Wouldn’t it be nice if we could approach one another, and notice when we are being approached. Those quiet steps forward could be the beginning of knowing one and another more deeply, and the forgiveness that ensues from that knowledge.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

The Awareness Exercise

NEW MEDITATION EXERCISE: The Awareness Exercise will help you wake up to the world around you and find peace. Find a quiet spot and meditate for 13 minutes to Michael Posnick soothing guidance.

"Stillness is a fence around wisdom." - Jewish Proverb

NEW MEDITATION EXERCISE: The Awareness Exercise will help you wake up to the world around you and find peace. Find a quiet spot and meditate for 13 minutes to Michael Posnick soothing guidance.

This exercise will wait for you right here, so make it a habit and put it on to start your days in a calming way or when you need a moment to relax.

Meditation opens the way to greater awareness, to living in the present with clarity and unfettered perception. Seeing things as they are enables us to accept what is and to act according to need.

Join Michael's weekly Meditation Chevrutah on Wednesday's @ 7 PM :

Through a series of experiential exercises, study and discussion, our chevrutah will provide an introduction to this ancient, universal practice and provide direction for those who would like to continue. Meditation is a means of self-discovery and whole-hearted participation in the divine play of creation. All forms of Jewish meditation lead to devekut, union with the divine.

Maoz Tsur

by Rabbi Misha

Before I share some thoughts on Hanukkah in advance of our celebration tomorrow, I’d like to acknowledge the anxiety and fear that the discussion in the Supreme Court on Wednesday may have provoked in many of you, especially women.

Dear friends,

Before I share some thoughts on Hanukkah in advance of our celebration tomorrow, I’d like to acknowledge the anxiety and fear that the discussion in the Supreme Court on Wednesday may have provoked in many of you, especially women. I find myself seriously impacted by the prospect of this decision, and have spent much of the last weeks thinking about the deeper meanings of this debate, and these two words “choice” and “life.” I will share some thoughts about all of this in the weeks ahead, and we are planning to address it in some of our gatherings as well, but for now I will just re-iterate that in the Jewish tradition the needs of the woman clearly supersede those of the fetus growing in her womb. If any of you would like to talk with me about this, or to organize around this issue please reach out.

We sing this song after candle lighting every night:

Ma'oz tsur yeshu'ati

lecha na'eh leshabeakh.

Tikon beit tefilati

vesham todah nezaveakh.

Le'et tachin matbeakh

mitsar hamnabeakh,

'az 'egmor beshir mizmor

khanukat hamizbeakh.

Poetry is hard to translate, which is why the translations out there are so terrible. Here’s one:

Rock of ages

Crown this praise

Light and songs to you we raise

Our will you strengthen

To fight for our redemption

It’s amazing how what people call a translation can offer nothing at all of the intention of the poet. I don’t know that I can do much better in poetic form, but I’ll try and give a sense of it in prose.

Maoz is a fortress, the place of condensed strength that cannot be broken.

Tsur is a foundational rock, the rock within a mountain that will never in our lifetime move. It is the one stable, constant and true piece of reality.

So Maoz tsur is the strongest inner core of the foundational rock.

Yeshuati means my redemption or salvation. My chance for improvement, for rising above, for becoming one with truth and goodness despite everything else going wrong in my world.

So Maoz tsur yeshuati is the strongest inner core of the foundational rock of my redemption. Fortress of the never changing rock of my best self.

Then we say – lecha na'eh leshabeach: to you, oh fortress, is it proper to give praise.

Tikon beit tefilati – literally the house of my prayer will be established. Here we clearly reference the Hanukkah story, and the return to the temple. But we can read this as any temple, the temple of our bodies, the place where we find peace, the home of our silence. This place will be established. And when it is, as we succeed occasionally in doing, then:

vesham todah nezaveakh: We will make an offering of gratitude there. When we manage to find this place of peace, we are able to see what we have, and to feel and express our gratitude with a zevach, a sacrificial gift that we offer out of love. Tomorrow at the party we will be making care packages for seniors with mental and financial problems. That will be our zevach todah, our gratitude offering.

We end the verse with these words:

'az 'egmor beshir mizmor

khanukat hamizbeakh.

Then I will conclude with a song. And what will that song accomplish? It will Hanukkah the alter; it will dedicate that alter of offering, the temple of our silence, and the work that is ahead of us to that fortress of truth, justice and goodness.

This medieval poem continues with several more verses, each one detailing a different dark time in our history. It is a poetic map of Antisemitic moments and sentiments which we somehow overcame. In each of these times of fear and oppression we managed to return to Maoz Tzur, this unshakeable truth at our core, this home, this quiet self. We managed, we could say, to return to YHVH.

Tomorrow we will acknowledge the ongoing problem of antisemitism, and look for our Maoz Tzur today. Our musical offering will be plentiful, with a special collection of incredible musicians including Frank London, Meg Okura, Trip Dudley and Yonatan Gutfeld. We will hear stories from elders, take part in an immersive play, fill our bellies with fancy latkes and ring the bells that still can ring.

Chag sameach and see you tomorrow at 3:30 at Judson.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

MUSIC: Shalom Aleichem

Shalom Aleichem (Hebrew: שָׁלוֹם עֲלֵיכֶם, 'Peace be upon you') is a traditional song sung by Jews every Friday night upon returning home from synagogue prayer.

This week's Music Video - Shalom Aleichem

Shalom Aleichem (Hebrew: שָׁלוֹם עֲלֵיכֶם, 'Peace be upon you') is a traditional song sung by Jews every Friday night upon returning home from synagogue prayer. It signals the arrival of the Shabbat, welcoming the angels who accompany a person home on the eve of the Shabbat. The custom of singing "Shalom Aleichem" on Friday night before Eshes Chayiland Kiddush is now nearly universal among religious Jews.

Tripp Dudley : Tabla

Marandi Hostetter : Violin

John Murchison : Bass

Yonatan Gutfeld : Guitar and singing

Rabbi Misha Shulman : singing

Thank you

by Rabbi Misha

A prayer of gratitude from the daily prayers.

Dear friends,

A prayer of gratitude from the daily prayers:

We thank you

Our fountain

And fountain of our mothers and fathers

Slow painter of our lives,

Watchful keeper of our hope

In every generation, that's You.

We continue to thank you

By telling your tales of love:

Our lives in your hands

Our spirits in your care

Your miracles accompanying us day by day

Your evening wonders

Your morning silence

Your afternoon delights.

Goodness; whose compassion will not end.

Compassion; who won't stop acting like a lover.

Whatever’s left of us turns to face You

Now

For all of it

Be blessed

Be praised

Be carried on our lips

And hearts and minds

Always

מוֹדִים אֲנַֽחְנוּ לָךְ שָׁאַתָּה הוּא יְהֹוָה אֱלֹהֵֽינוּ וֵאלֹהֵי אֲבוֹתֵֽינוּ לְעוֹלָם וָעֶד צוּר חַיֵּֽינוּ מָגֵן יִשְׁעֵֽנוּ אַתָּה הוּא לְדוֹר וָדוֹר נֽוֹדֶה לְּךָ וּנְסַפֵּר תְּהִלָּתֶֽךָ עַל־חַיֵּֽינוּ הַמְּ֒סוּרִים בְּיָדֶֽךָ וְעַל נִשְׁמוֹתֵֽינוּ הַפְּ֒קוּדוֹת לָךְ וְעַל נִסֶּֽיךָ שֶׁבְּכָל יוֹם עִמָּֽנוּ וְעַל נִפְלְ֒אוֹתֶֽיךָ וְטוֹבוֹתֶֽיךָ שֶׁבְּ֒כָל עֵת עֶֽרֶב וָבֹֽקֶר וְצָהֳרָֽיִם הַטּוֹב כִּי לֹא כָלוּ רַחֲמֶֽיךָ וְהַמְ֒רַחֵם כִּי לֹא תַֽמּוּ חֲסָדֶֽיךָ מֵעוֹלָם קִוִּֽינוּ לָךְ:

וְעַל־כֻּלָּם יִתְבָּרַךְ וְיִתְרוֹמַם שִׁמְךָ מַלְכֵּֽנוּ תָּמִיד לְעוֹלָם וָעֶד:

Wishing you all a happy Thanksgiving weekend!

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

MUSIC: Warrior of the Light

Warriors of the Light is this week's music video.

Warriors of the Light is this week's music video.

בָּאנוּ חֹשֶךְ לְגָרֵשׁ.

בְּיָדֵינוּ אוֹר וָאֵשׁ.

כָּל אֶחָד הוּא אוֹר קָטָן,

וְכֻלָּנוּ - אוֹר אֵיתָן.

סוּרָה חֹשֶךְ! הָלְאָה שְׁחוֹר!

סוּרָה מִפְּנֵי הָאוֹר!

We’re the warriors of the light

Come to bust away the night

Each of us is one small flame

And together we exclaim:

Get away darkness

Onward night

We will turn you into light

Get away darkness

Onward night

We will turn you into light

Tripp Dudley : Tabla

Marandi Hostetter : Violin

John Murchison : Bass

Yonatan Gutfeld : Guitar and singing

Rabbi Misha Shulman : singing

Us and the Stars

by Rabbi Misha

Imagine you knew the constellations as well as you knew your neighborhood. Like you knew how to get from the subway stop to your apartment, you knew the way from the Big Dipper to Orion.

Ben Shahn

Dear friends,

Imagine you knew the constellations as well as you knew your neighborhood. Like you knew how to get from the subway stop to your apartment, you knew the way from the Big Dipper to Orion. Like you could make your way from Lincoln Center to Grand Central you could follow the stars from Aquarius to Gemini. This used to be a much more common human ability but it was always rare. In the Talmud we find one true expert of the heavens. “Shmuel said: the paths of the skies are as clear to me as the paths of Nehardea (the town he lived in).” An intimacy with the night skies is something we city dwellers seem to have largely lost.

A couple weeks ago the stars entered my living room. My cousin shipped me a painting that belonged to my grandmother, with text from the Book of Job under an abstract depiction of the night sky. Painted by Ben Shahn, a Jew who traversed the paths from the old world to the US, from Cheder (parochial school) to the world of political art, the painting has brought with it soft questions of our place in the universe, gentle queries about the ways we walk the earth, and new readings of the Book of Job.

The stars serve a few different purposes according to our creation story.

והיו לאתת ולמועדים ולימים ושנים

They will serve as signs, and holidays and days and years.

Signs that suggest where we might go. Holidays that we can stop and mark special times. Days that we might stay connected with the slow movement of the everyday. Years that we can feel the flow of our lives, its circularity as well as its changing nature.

Life here on the ground beneath the stars is not always easy. We struggle to see those signs up there.

The text in the painting is part of God’s speech to the ultimate sufferer, Job toward the end of the book. You’ll recall that Job was a rich, happy man, who had his entire life implode, losing his children, his wealth and health, and his trust in the goodness of God. After thirty some chapters of theological poetry about the question of bad things happening to good people, God finally speaks. God’s speech is most easily understood as a scolding. General sentiment: Who are you to complain at me, you little speck of dust?! But staring at these verses sitting under Shahn’s constellations has softened God’s words from angry rhetorical questions, to just plain questions:

הַֽ֭תְקַשֵּׁר מַעֲדַנּ֣וֹת כִּימָ֑ה אֽוֹ־מֹשְׁכ֖וֹת כְּסִ֣יל תְּפַתֵּֽחַ׃

הֲתֹצִ֣יא מַזָּר֣וֹת בְּעִתּ֑וֹ וְ֝עַ֗יִשׁ עַל־בָּנֶ֥יהָ תַנְחֵֽם׃

הֲ֭יָדַעְתָּ חֻקּ֣וֹת שָׁמָ֑יִם אִם־תָּשִׂ֖ים מִשְׁטָר֣וֹ בָאָֽרֶץ׃

Can you tie sweet cords to Pleiades

Or undo the reins of Orion?

Can you lay out the constellations each month,

Or keep the North Star in her mothering spot?

Do you know the laws of the sky

Or the way they govern the earth?

There are answers to these questions beyond the simple “No” that most people have seen in them. Instead of a slap on the wrist or a trodding upon I have begun to see them as an invitation to participate in the heavenly play. Sitting under the loving painted sky I can’t help but notice how Shahn has tied sweet cords to Plaides, connected me to them and them to the other constellations. Or how Shmuel, like many star gazers learned the laws of the sky, and how some part of me understands the way they are connected to my life. Even though we rarely see the vast majority of the stars, many of us still know the way they were aligned on the day, the hour and the minute we came out from the dark to the place where they can be seen. There is hidden love and protection in this universe that we can look for, imagine, discover, take part in and know, even in - especially in - our darkest moments.

Wishing you a shabbat filled with stars.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

MUSIC: Tehila - Psalm 5

Watch and listen to another Tehila, a musical improvisation inspired by Psalm 5.

Played on qanun by John Murchison and introduced by rabbi Misha Shulman.

This week’s video is another Tehila, a musical improvisation inspired by Psalm 5.

Played on qanun by John Murchison and introduced by rabbi Misha Shulman.

לַמְנַצֵּ֥חַ אֶֽל־הַנְּחִיל֗וֹת מִזְמ֥וֹר לְדָוִֽד׃

For the leader; on neḥiloth. A psalm of David.

אֲמָרַ֖י הַאֲזִ֥ינָה ׀ יְהוָ֗ה בִּ֣ינָה הֲגִֽיגִי׃

Give ear to my speech, O LORD; consider my utterance.

הַקְשִׁ֤יבָה ׀ לְק֬וֹל שַׁוְעִ֗י מַלְכִּ֥י וֵאלֹהָ֑י כִּֽי־אֵ֝לֶ֗יךָ אֶתְפַּלָּֽל׃

Heed the sound of my cry, my king and God, for I pray to You.

יְֽהוָ֗ה בֹּ֭קֶר תִּשְׁמַ֣ע קוֹלִ֑י בֹּ֥קֶר אֶֽעֱרָךְ־לְ֝ךָ֗ וַאֲצַפֶּֽה׃

Hear my voice, O LORD, at daybreak; at daybreak I plead before You, and wait.

כִּ֤י ׀ לֹ֤א אֵֽל־חָפֵ֘ץ רֶ֥שַׁע ׀ אָ֑תָּה לֹ֖א יְגֻרְךָ֣ רָֽע׃

For You are not a God who desires wickedness; evil cannot abide with You;

לֹֽא־יִתְיַצְּב֣וּ הֽ֭וֹלְלִים לְנֶ֣גֶד עֵינֶ֑יךָ שָׂ֝נֵ֗אתָ כָּל־פֹּ֥עֲלֵי אָֽוֶן׃

wanton men cannot endure in Your sight. You detest all evildoers;

תְּאַבֵּד֮ דֹּבְרֵ֪י כָ֫זָ֥ב אִישׁ־דָּמִ֥ים וּמִרְמָ֗ה יְתָ֘עֵ֥ב ׀ יְהוָֽה׃

You doom those who speak lies; murderous, deceitful men the LORD abhors.

וַאֲנִ֗י בְּרֹ֣ב חַ֭סְדְּךָ אָב֣וֹא בֵיתֶ֑ךָ אֶשְׁתַּחֲוֶ֥ה אֶל־הֵֽיכַל־קָ֝דְשְׁךָ֗ בְּיִרְאָתֶֽךָ׃

But I, through Your abundant love, enter Your house; I bow down in awe at Your holy temple.

יְהוָ֤ה ׀ נְחֵ֬נִי בְצִדְקָתֶ֗ךָ לְמַ֥עַן שׁוֹרְרָ֑י הושר [הַיְשַׁ֖ר] לְפָנַ֣י דַּרְכֶּֽךָ׃

O LORD, lead me along Your righteous [path] because of my watchful foes; make Your way straight before me.

כִּ֤י אֵ֪ין בְּפִ֡יהוּ נְכוֹנָה֮ קִרְבָּ֪ם הַ֫וּ֥וֹת קֶֽבֶר־פָּת֥וּחַ גְּרוֹנָ֑ם לְ֝שׁוֹנָ֗ם יַחֲלִֽיקוּן׃

For there is no sincerity on their lips;their heart is [filled with] malice; their throat is an open grave; their tongue slippery.

הַֽאֲשִׁימֵ֨ם ׀ אֱֽלֹהִ֗ים יִפְּלוּ֮ מִֽמֹּעֲצ֪וֹתֵ֫יהֶ֥ם בְּרֹ֣ב פִּ֭שְׁעֵיהֶם הַדִּיחֵ֑מוֹ כִּי־מָ֥רוּ בָֽךְ׃

Condemn them, O God; let them fall by their own devices; cast them out for their many crimes, for they defy You.

וְיִשְׂמְח֨וּ כָל־ח֪וֹסֵי בָ֡ךְ לְעוֹלָ֣ם יְ֭רַנֵּנוּ וְתָסֵ֣ךְ עָלֵ֑ימוֹ וְֽיַעְלְצ֥וּ בְ֝ךָ֗ אֹהֲבֵ֥י שְׁמֶֽךָ׃

But let all who take refuge in You rejoice, ever jubilant as You shelter them; and let those who love Your name exult in You.

כִּֽי־אַתָּה֮ תְּבָרֵ֪ךְ צַ֫דִּ֥יק יְהוָ֑ה כַּ֝צִּנָּ֗ה רָצ֥וֹן תַּעְטְרֶֽנּוּ׃

For You surely bless the righteous man, O LORD, encompassing him with favor like a shield.

Strong Women

by Rabbi Misha

Divine though it may be, the Torah was written by and about men.

Judy Chicago, The Creation from the Birth Project, 1982

Dear friends,

Divine though it may be, the Torah was written by and about men. We can see direct lines between the Tanach and the abortion law in Texas, the backwards attitude toward parental leave in this country and the war on women around the world. All of this provides one of the most exciting opportunities religion has to offer: the chance to participate in reshaping it through new practices and re-interpretation of the ancient texts. I feel empowered when I can see the direct line not between the Torah and the current expressions of the patriarchy but between the Torah and the work of feminist artists like Judy Chicago, or even singers like Cardi B.

I get especially excited when a young person clues me in to the subversive feminine voice in the Torah. These past weeks I’ve been learning from a 13 year old young woman named Willow, a member of the Shul who will be rising to the Torah at her Bat Mitzvah tomorrow. She looks at this week’s parashah and doesn’t see the story of Jacob leaving Canaan to Mesopotamia to find a wife, but of Rachel, who sets her eyes on a young man that turns up at the well, and decides to create a family with him.

When Rachel’s father, Laban tricks Jacob into having sex with her older sister, Leah (and in that act solidifying their marriage), the Torah points our attention to Jacob. But in Willow’s narrative we are looking at how this impacts Rachel, as well as Leah. When a decision to leave and head back to Canaan after 20 years happens, Willow sees the two women as the initiators of that move.

The amazing thing is that once you make that switch in your mind it’s hard to see the text of Genesis as anything but that way.

In God, Sex and The Women of the Bible, Rabbi Shoni Labowitz z”l wrote: “When you change the story, you can change the whole culture. This is what the patriarchal era did in history, and women have the power now to correct it.” Labowitz, who knew well how the (male) rabbis over the centuries diverted the story toward an even more male-centered approach, seems to be suggesting that the Torah may be more gender-neutral than we are used to thinking about it, and can therefore be reclaimed by women through interpretation.

The contemporary practice of Midrashey Nashim, stories and commentaries on the Torah written by women is an important piece of this work. Women like Tamar Biala and Chana Thompson, who take the traditional form of Midrash, stories that flesh out the stories in the bible, but do it with a woman’s viewpoint are hard at work. Yael Kanarek, whose Re-gendered Bible flips all the genders in the Torah to create a new impression on the reader, is a downtown artist deeply engaged in Torah and its reboot.

And just like in any of the struggles for women’s liberation, we shouldn’t forget that men can play an important role as well as allies. The struggle for a just Torah is the struggle for a just society for all of us. Perhaps we could all start with hearing the women in the stories of this week’s parashah, as Willow has helped me do.

If you’d like to give that a try, a wonderful place to start is in the Shul’s Women of the Bible Chevrutah, led by Elana Ponet. For more info click HERE.

I hope you can join us this evening for Kabbalat shabbat at the 14th Street Y (or on Zoom), where we will have a conversation about one of Rachel’s strongest and strangest moments in Torah, and the echoes we might see of her actions today. We will be joined by Yacine Boulares, a wonderful French-Tunisian saxophone player and composer.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

MUSIC: Tehila - Psalm 69

Watch and listen to a Tehila, a musical improvisation inspired by Psalm 69.

Played on the Violin by Marandi Hostetter and introduced by rabbi Misha Shulman.

This week’s video is a Tehila, a musical improvisation inspired by Psalm 69.

Played on the Violin by Marandi Hostetter and introduced by rabbi Misha Shulman.

לַמְנַצֵּ֬חַ עַֽל־שׁוֹשַׁנִּ֬ים לְדָוִֽד׃

For the leader. On shoshannim.Of David.

הוֹשִׁיעֵ֥נִי אֱלֹהִ֑ים כִּ֤י בָ֖אוּ מַ֣יִם עַד־נָֽפֶשׁ׃

Deliver me, O God, for the waters have reached my neck;

טָבַ֤עְתִּי ׀ בִּיוֵ֣ן מְ֭צוּלָה וְאֵ֣ין מָעֳמָ֑ד בָּ֥אתִי בְמַעֲמַקֵּי־מַ֝֗יִם וְשִׁבֹּ֥לֶת שְׁטָפָֽתְנִי׃

I am sinking into the slimy deep and find no foothold; I have come into the watery depths; the flood sweeps me away.

יָגַ֣עְתִּי בְקָרְאִי֮ נִחַ֪ר גְּר֫וֹנִ֥י כָּל֥וּ עֵינַ֑י מְ֝יַחֵ֗ל לֵאלֹהָֽי׃

I am weary with calling; my throat is dry; my eyes fail while I wait for God.

רַבּ֤וּ ׀ מִשַּׂעֲר֣וֹת רֹאשִׁי֮ שֹׂנְאַ֪י חִ֫נָּ֥ם עָצְמ֣וּ מַ֭צְמִיתַי אֹיְבַ֣י שֶׁ֑קֶר אֲשֶׁ֥ר לֹא־גָ֝זַ֗לְתִּי אָ֣ז אָשִֽׁיב׃

More numerous than the hairs of my head are those who hate me without reason; many are those who would destroy me, my treacherous enemies. Must I restore what I have not stolen?

אֱֽלֹהִ֗ים אַתָּ֣ה יָ֭דַעְתָּ לְאִוַּלְתִּ֑י וְ֝אַשְׁמוֹתַ֗י מִמְּךָ֥ לֹא־נִכְחָֽדוּ׃

God, You know my folly; my guilty deeds are not hidden from You.

אַל־יֵ֘בֹ֤שׁוּ בִ֨י ׀ קֹוֶיךָ֮ אֲדֹנָ֥י יְהוִ֗ה צְבָ֫א֥וֹת אַל־יִכָּ֣לְמוּ בִ֣י מְבַקְשֶׁ֑יךָ אֱ֝לֹהֵ֗י יִשְׂרָאֵֽל׃

Let those who look to You, O Lord, God of hosts, not be disappointed on my account; let those who seek You, O God of Israel, not be shamed because of me.

כִּֽי־עָ֭לֶיךָ נָשָׂ֣אתִי חֶרְפָּ֑ה כִּסְּתָ֖ה כְלִמָּ֣ה פָנָֽי׃

It is for Your sake that I have been reviled, that shame covers my face;

מ֭וּזָר הָיִ֣יתִי לְאֶחָ֑י וְ֝נָכְרִ֗י לִבְנֵ֥י אִמִּֽי׃

I am a stranger to my brothers, an alien to my kin.

כִּֽי־קִנְאַ֣ת בֵּיתְךָ֣ אֲכָלָ֑תְנִי וְחֶרְפּ֥וֹת ח֝וֹרְפֶ֗יךָ נָפְל֥וּ עָלָֽי׃

My zeal for Your house has been my undoing; the reproaches of those who revile You have fallen upon me.

וָאֶבְכֶּ֣ה בַצּ֣וֹם נַפְשִׁ֑י וַתְּהִ֖י לַחֲרָפ֣וֹת לִֽי׃

When I wept and fasted, I was reviled for it.

וָאֶתְּנָ֣ה לְבוּשִׁ֣י שָׂ֑ק וָאֱהִ֖י לָהֶ֣ם לְמָשָֽׁל׃

I made sackcloth my garment; I became a byword among them.

יָשִׂ֣יחוּ בִ֭י יֹ֣שְׁבֵי שָׁ֑עַר וּ֝נְגִינ֗וֹת שׁוֹתֵ֥י שֵׁכָֽר׃

Those who sit in the gate talk about me; I am the taunt of drunkards.

וַאֲנִ֤י תְפִלָּתִֽי־לְךָ֨ ׀ יְהוָ֡ה עֵ֤ת רָצ֗וֹן אֱלֹהִ֥ים בְּרָב־חַסְדֶּ֑ךָ עֲ֝נֵ֗נִי בֶּאֱמֶ֥ת יִשְׁעֶֽךָ׃

As for me, may my prayer come to You, O LORD, at a favorable moment; O God, in Your abundant faithfulness, answer me with Your sure deliverance.

הַצִּילֵ֣נִי מִ֭טִּיט וְאַל־אֶטְבָּ֑עָה אִנָּצְלָ֥ה מִ֝שֹּֽׂנְאַ֗י וּמִמַּֽעֲמַקֵּי־מָֽיִם׃

Rescue me from the mire; let me not sink; let me be rescued from my enemies, and from the watery depths.

אַל־תִּשְׁטְפֵ֤נִי ׀ שִׁבֹּ֣לֶת מַ֭יִם וְאַל־תִּבְלָעֵ֣נִי מְצוּלָ֑ה וְאַל־תֶּאְטַר־עָלַ֖י בְּאֵ֣ר פִּֽיהָ׃

Let the floodwaters not sweep me away; let the deep not swallow me; let the mouth of the Pit not close over me.

עֲנֵ֣נִי יְ֭הוָה כִּי־ט֣וֹב חַסְדֶּ֑ךָ כְּרֹ֥ב רַ֝חֲמֶ֗יךָ פְּנֵ֣ה אֵלָֽי׃

Answer me, O LORD, according to Your great steadfastness; in accordance with Your abundant mercy turn to me;

וְאַל־תַּסְתֵּ֣ר פָּ֭נֶיךָ מֵֽעַבְדֶּ֑ךָ כִּֽי־צַר־לִ֝֗י מַהֵ֥ר עֲנֵֽנִי׃

do not hide Your face from Your servant, for I am in distress; answer me quickly.

קָרְבָ֣ה אֶל־נַפְשִׁ֣י גְאָלָ֑הּ לְמַ֖עַן אֹיְבַ֣י פְּדֵֽנִי׃

Come near to me and redeem me; free me from my enemies.

אַתָּ֤ה יָדַ֗עְתָּ חֶרְפָּתִ֣י וּ֭בָשְׁתִּי וּכְלִמָּתִ֑י נֶ֝גְדְּךָ֗ כָּל־צוֹרְרָֽי׃

You know my reproach, my shame, my disgrace; You are aware of all my foes.

חֶרְפָּ֤ה ׀ שָֽׁבְרָ֥ה לִבִּ֗י וָֽאָ֫נ֥וּשָׁה וָאֲקַוֶּ֣ה לָנ֣וּד וָאַ֑יִן וְ֝לַמְנַחֲמִ֗ים וְלֹ֣א מָצָֽאתִי׃

Reproach breaks my heart, I am in despair;I hope for consolation, but there is none, for comforters, but find none.

וַיִּתְּנ֣וּ בְּבָרוּתִ֣י רֹ֑אשׁ וְ֝לִצְמָאִ֗י יַשְׁק֥וּנִי חֹֽמֶץ׃

They give me gall for food, vinegar to quench my thirst.

יְהִֽי־שֻׁלְחָנָ֣ם לִפְנֵיהֶ֣ם לְפָ֑ח וְלִשְׁלוֹמִ֥ים לְמוֹקֵֽשׁ׃

May their table be a trap for them, a snare for their allies.

תֶּחְשַׁ֣כְנָה עֵ֭ינֵיהֶם מֵרְא֑וֹת וּ֝מָתְנֵ֗יהֶם תָּמִ֥יד הַמְעַֽד׃

May their eyes grow dim so that they cannot see; may their loins collapse continually.

שְׁפָךְ־עֲלֵיהֶ֥ם זַעְמֶ֑ךָ וַחֲר֥וֹן אַ֝פְּךָ֗ יַשִּׂיגֵֽם׃

Pour out Your wrath on them; may Your blazing anger overtake them;

תְּהִי־טִֽירָתָ֥ם נְשַׁמָּ֑ה בְּ֝אָהֳלֵיהֶ֗ם אַל־יְהִ֥י יֹשֵֽׁב׃

may their encampments be desolate; may their tents stand empty.

כִּֽי־אַתָּ֣ה אֲשֶׁר־הִכִּ֣יתָ רָדָ֑פוּ וְאֶל־מַכְא֖וֹב חֲלָלֶ֣יךָ יְסַפֵּֽרוּ׃

For they persecute those You have struck; they talk about the pain of those You have felled.

תְּֽנָה־עָ֭וֺן עַל־עֲוֺנָ֑ם וְאַל־יָ֝בֹ֗אוּ בְּצִדְקָתֶֽךָ׃

Add that to their guilt; let them have no share of Your beneficence;

יִ֭מָּחֽוּ מִסֵּ֣פֶר חַיִּ֑ים וְעִ֥ם צַ֝דִּיקִ֗ים אַל־יִכָּתֵֽבוּ׃

may they be erased from the book of life, and not be inscribed with the righteous.

וַ֭אֲנִי עָנִ֣י וְכוֹאֵ֑ב יְשׁוּעָתְךָ֖ אֱלֹהִ֣ים תְּשַׂגְּבֵֽנִי׃

But I am lowly and in pain; Your help, O God, keeps me safe.

אֲהַֽלְלָ֣ה שֵׁם־אֱלֹהִ֣ים בְּשִׁ֑יר וַאֲגַדְּלֶ֥נּוּ בְתוֹדָֽה׃

I will extol God’s name with song, and exalt Him with praise.

וְתִיטַ֣ב לַֽ֭יהוָה מִשּׁ֥וֹר פָּ֗ר מַקְרִ֥ן מַפְרִֽיס׃

That will please the LORD more than oxen, than bulls with horns and hooves.

רָא֣וּ עֲנָוִ֣ים יִשְׂמָ֑חוּ דֹּרְשֵׁ֥י אֱ֝לֹהִ֗ים וִיחִ֥י לְבַבְכֶֽם׃

The lowly will see and rejoice; you who are mindful of God, take heart!

כִּֽי־שֹׁמֵ֣עַ אֶל־אֶבְיוֹנִ֣ים יְהוָ֑ה וְאֶת־אֲ֝סִירָ֗יו לֹ֣א בָזָֽה׃

For the LORD listens to the needy, and does not spurn His captives.

יְֽ֭הַלְלוּהוּ שָׁמַ֣יִם וָאָ֑רֶץ יַ֝מִּ֗ים וְֽכָל־רֹמֵ֥שׂ בָּֽם׃

Heaven and earth shall extol Him, the seas, and all that moves in them.

כִּ֤י אֱלֹהִ֨ים ׀ י֘וֹשִׁ֤יעַ צִיּ֗וֹן וְ֭יִבְנֶה עָרֵ֣י יְהוּדָ֑ה וְיָ֥שְׁבוּ שָׁ֝֗ם וִירֵשֽׁוּהָ׃

For God will deliver Zion and rebuild the cities of Judah; they shall live there and inherit it;

וְזֶ֣רַע עֲ֭בָדָיו יִנְחָל֑וּהָ וְאֹהֲבֵ֥י שְׁ֝מ֗וֹ יִשְׁכְּנוּ־בָֽהּ׃

the offspring of His servants shall possess it; those who cherish His name shall dwell there.

Wine, Cheese and Ben and Jerry's Ice Cream

by Rabbi Misha

This week I posted a note on the Shul’s Instagram about State Comptroller Tom DiNapoli’s decision to divest New York state’s pension fund from Unilever, the parent company of Ben and Jerry’s.

Dear friends,

This week I posted a note on the Shul’s Instagram about State Comptroller Tom DiNapoli’s decision to divest New York state’s pension fund from Unilever, the parent company of Ben and Jerry’s. DiNapoli based his decision on Cuomo’s 2016 executive order forbidding the state to do business with supporters of the Boycott Divestment and Sanctions movement (BDS). I wanted to take the time to lay out some of my thinking on this issue that is close to my heart, which led me to post about it, and, I’m sorry to say, upset some of you.

Before that, however I’d like to explain that I see my role as rabbi as one entangled with ethics and morality rather than “the news”. When I read the newspaper as Misha I have all kinds of thoughts and opinions about whatever I read. When I take action on an issue as Rabbi Misha it is because I see ethical implications which transcend the current moment and speak to the moral bedrock of our tradition and our people’s history. That was the case this week.

Let me also clarify that what I posted this week had little to do with BDS. That was actually one of the points I was trying to make: that DiNapoli was using an anti-BDS law to penalize a company for an action that has nothing to do with BDS. You see, BDS is a movement to boycott, divest and sanction the State of Israel as a whole. They make no distinction between Israel proper, the land inside the internationally recognized 1967 borders, and the Occupied Palestinian Territories. To the BDS movement as a whole, the Israeli settlers of Chavat Maon - who have beaten my father and terrorized and assaulted countless Palestinians - and the residents of the Jewish-Arab village Neve Shalom, are the same.

Ben and Jerry’s takes a different stance. Their action did not comment on the legitimacy or lack thereof of the State of Israel. They self-define as “Jewish supporters of the State of Israel.” The boycott they announced is limited solely to the Jewish settlements in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. They wrote in the NY Times that what they did is not a rejection of Israel but “of Israeli policy, which perpetuates an illegal occupation that is a barrier to peace and violates the basic human rights of the Palestinian people who live under the occupation.”

Throwing this kind of boycott into the same basket as BDS amounts to silencing criticism of the state. It’s the same as telling critics of Egypt or China or India--or any of the other countries around the world doing horrific things--to keep quiet. There is a reason why so many American Jews I meet are afraid to speak their minds, or even to hold an opinion on Israel/Palestine, and it has to do with messaging like this.

Ben and Jerry’s is not questioning the legitimacy of Israel. They are questioning the legitimacy of a brutal 54 year-long occupation, and the actions of the State of Israel to fill the territory with Jews and create a system of segregation and oppression.

Ben and Jerry’s is not saying that Israel is the worst country in the world. They know like we do that China is holding a million people in concentration camps and forcing them to pick the cotton that ends up on your clothes and mine. They know like we do that half of the population of Afghanistan and many other countries is under attack daily by the men who run it. They know that LGBTQ people are killed by the state in many countries in the world. They know that this country is still chasing black people at the border on horseback and keeps close to two million mostly black and brown people in prison.

The reason they singled out one government is because of what I began with. It has to do with who we are. They clearly identify with Israel. They care about what goes on there. They feel a stake in it. And they were moved to take a stand on the one country that claims to speak for them as Jews.

They’ve come to the same conclusion that many of the Israelis I know have arrived at: there’s something wrong with buying wine made in Jewish owned vineyards near Nablus, or cheese made in Jewish-owned farms outside of Hebron, both of which sit on lands confiscated from Palestinian farmers. It’s somehow different than wine or cheese from Binyamina, south of Haifa.

We could agree with them or we could disagree. But to try to silence them in this uninformed way, which doesn’t even rise to the standards of the executive order that DiNapoli claims as his reason (and the rest of the politicians in the state have been mum on), is wrong.

מבשרך לא תתעלם, implored Isaiah, Do not ignore your own flesh.

Ben and Jerry’s refused to ignore the pain they feel over their ancestral homeland. They are choosing to engage, rather than to step back and say: “Oh it’s just so crazy over there.” They’re choosing to step in, despite the serious financial damages they stand to lose, rather than to hide.

In this week’s Parashah we are introduced to our ancestor, Jacob, whose name will be changed next week. “You will no longer be called Jacob” the angel says to him. Jacob, the little brother of, the one who comes in the heel of (the literal meaning of his name), the follower who did what Mommy told him and ruined his relationship with his brother. No more of that. From now on, the angel tells him, you will have your own name, the name of one who doesn’t shy away, but struggles, leads and takes risks. “Your name will be Israel, because you have struggled with God and with humans and were not beaten.”

Israel means to wrestle. Whether or not we agree or disagree with what they’ve done, Ben and Jerry’s is wrestling with Zion. Let’s not divest from wrestling. I hope you write me back some wrestling notes with whatever you may be thinking or feeling about this flawed communication.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

MUSIC: Kuma Elohim

Watch and listen to Kuma Elohim. This is rabbi Misha’s melody for Psalms 86 verse 8.

This is rabbi Misha’s melody for Psalms 86 verse 8:

קוּמָ֣ה אֱ֭לֹהִים שָׁפְטָ֣ה הָאָ֑רֶץ כִּֽי־אַתָּ֥ה תִ֝נְחַ֗ל בְּכָל־הַגּוֹיִֽם׃

Arise, O God, judge the earth, for all the nations are Your possession.

Tripp Dudley : Tabla

Marandi Hostetter : Violin

John Murchison : Bass

Yonatan Gutfeld : Guitar and singing

Rabbi Misha Shulman : singing

MUSIC: Lecha Dodi

Watch and listen to ‘Come my friend’. Lecha Dodi is the hymn sung during the synagogue service on Friday night to welcome the Sabbath. It was composed by Solomon Alkabetz, a Kabbalist (mystic).

Lecha Dodi

‘Come my friend’ is the hymn sung during the synagogue service on Friday night to welcome the Sabbath. It was composed by Solomon Alkabetz, a Kabbalist (mystic).

Come beloved to meet the bride, to welcome the face of Shabbat.

Keep and remember spoken at once, we heard the one divinity.

She is One, and her name is One, in name, beauty, and song.

To greet her we go, for she is the source of blessing.

Poured from the ancient beginning, last in creation, first in mind.

Palace of the Queen, secret city, rise, shake off the dust.

Long have you sat in the valley of tears! Her compassion flows over you.

Wake up wake up! For your light has come, rise and shine.

Woken awoken speak a song, the glory of spirit shines over you.

Come in peace, crown of the beloved, in joy and radiance

From the faith of those who are a treasure, come bride, come.

Tripp Dudley : Darbuka

Marandi Hostetter : Violin

John Murchison : Qanun

Yonatan Gutfeld : Guitar and singing

Rabbi Misha Shulman : singing