Sort by Category

Ready to Begin

by Rabbi Misha

When you go to the theater there is one moment you can always count on to be beautiful, and that’s when the house lights go down on the crowd and the play is about to begin.

Shehecheyanu in Carroll Gardens

Dear friends,

When you go to the theater there is one moment you can always count on to be beautiful, and that’s when the house lights go down on the crowd and the play is about to begin. It’s a moment of quiet anticipation, where it’s easy to feel present, where the excitement for what is coming is real. In the Jewish calendar, believe it or not, that’s the moment we’re in.

What might this year bring?

I admit, that’s a scary question. But this rather magical week that passed reminded me that it’s also an incredibly exciting one.

What made this week magical is that, along with the frightful political events, I had the great fortune to experience three beautiful beginnings. On Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday we opened each of the three Brooklyn branches of our Hebrew school, the School for Creative Judaism (with this Tuesday coming up in the Village!). Each opening was a sweet, happy gathering, overflowing with young wisdom, wonder and joy. It’s so easy to forget how centering hanging out with kids can be.

“Where does light come from,” Arnan, our Senior Educator asked the kids in Windsor Terrace. Our annual theme at the School is the Year of the Artists, so one of our focuses will be light.

“The sun!”

“Only the sun?” Arnan was expecting this answer.

The follow-up question opened the gates. Estella talked about the heart. Otto offered Shabbat candles. Jack spoke about encouraging one another. Suddenly we were all in a space of wonder. Where does light actually come from?

In Clinton Hill when we sat down in our ma’agal (circle), we sang Sim Shalom, one of the daily prayers for peace, in which we ask:

ברכנו אבינו כולנו כאחד באור פניך

“bless us, one and all with the light emanating from Your face.”

Reflecting on the lack of peace in Israel and Palestine, among other places, Laila asked a simple question: "Why can’t they just share?" What was amazing about what ensued is that nobody answered with “it’s complicated.” Instead, kids, pre-teens, and adults thought together about the question. One suggested it’s the leadership’s fault. Another talked about fear. A third spoke about history. This is beginning. A true engagement with a real question in search of the light of understanding.

In Carroll Gardens things got physical. Instead of the Torah’s story of creation I shared with the group a Kabbalistic one, known as Shvirat Hakelim, The Breaking of the Vessels. When God wanted to create the world, She knew it has to be done with light. So, as a first step, God prepared ten vessels to hold the primordial light. When God poured the light into them, it didn’t go so well. Out of the ten vessels, only three survived. The other seven exploded into millions of pieces. Our job, according to the Kabbalists, is to collect the infinite shards of the vessels, so that we can hold the light.

I never quite understood this story, so I asked the kids to physicalize it into a moving statue. After each group performed their mini-plays, I asked them what they thought the story means. Alex said it’s how the stars are created. Misha Y. said it means God makes mistakes. “The world is ours to fix,” he announced.

When we sang the Shehecheyanu with each branch, we all started jumping and clapping our hands. How lucky are we! We’re alive. We’re here. We’re ready to begin.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

What's Time Well Spent?

by Rabbi Misha

After ten days of probing, difficult questions, this morning’s Soul Math challenge quite literally cut to the chase. Excellent Jew that he was, Ibn Paquda offers an answer to the question of our purpose - in the form of another question: How much time are you wasting?

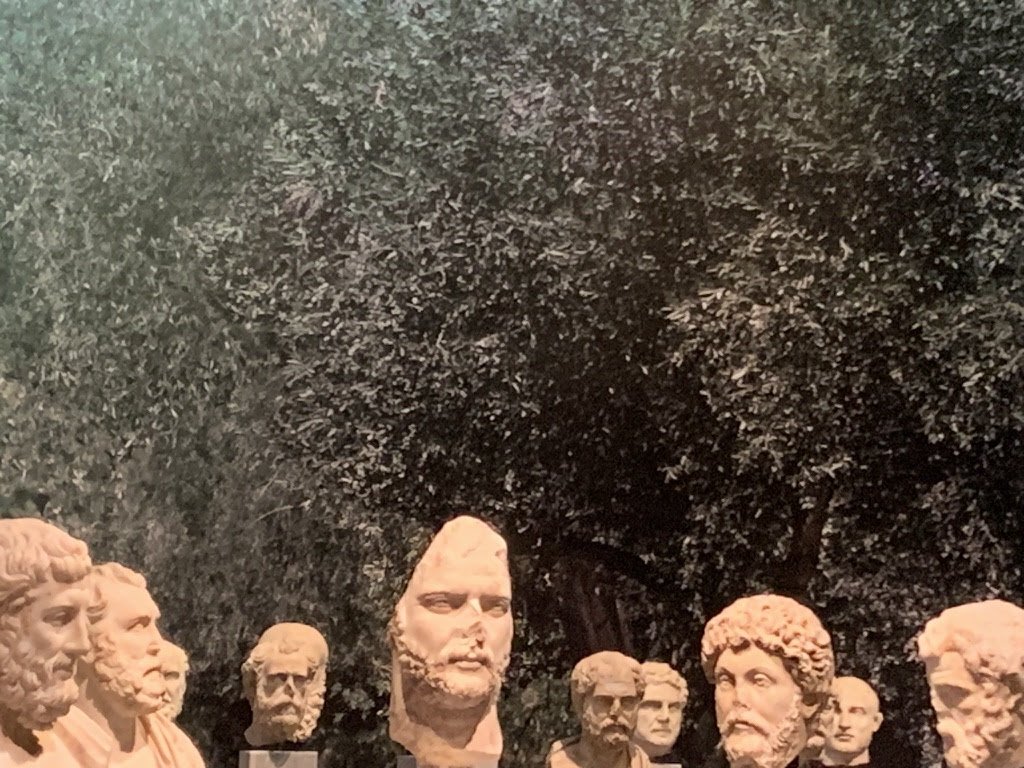

Immersed in the kishkes of existence at the National Archaelogical Museum in Athens.

Dear friends,

After ten days of probing, difficult questions, this morning’s Soul Math challenge quite literally cut to the chase. Excellent Jew that he was, Ibn Paquda offers an answer to the question of our purpose - in the form of another question: How much time are you wasting?

Naturally, this brings up the question – what is wasted time, versus time well spent?

Let’s start by negation:

Last night I got home after a busy day around 11pm. I opened my laptop and sought to wind down by... checking the latest election polls. Yesterday’s Soul Math question was what we are doing that we think no one sees, which we are embarrassed about. Well, now you all know one way in which I completely throw into the garbage my precious time. How embarrassing for me.

Why do I do it? I’m seeking confirmation of my biases. I’m seeking material for my mind to chew. I’m seeking to worry less. But am I? Looking at polls, if one is concerned about the state of the world, is a classic example of feeding one’s anxiety. It pulls me away from the nighttime all around me, the calming cycle of the moon and the stars and the trees outside my window, which offer the promise of continued peace, and into the meaningless noise of the present moment.

A better hour was spent this morning talking to a member of the Shul’s Rabbinic Chavurah, cantor and teacher Yoni Kretzmer. I asked him what defines good use of time?

YK: There’s a Talmudic argument between two rabbis about whether making a living is a proper use of time, which might help us dig into this. The Torah says: “Vehagita bo yomam valayla,” “Think about it (the Torah) day and night.” Rabbi Yishmael says that this proves that making a living is a great use of time, because we can easily think and study in the morning and the evening, so obviously we are being encouraged to work the rest of the day in between the two.

Rabban Yochanan Ben Zakai says that’s silly, and what we are clearly being told by “day and night” is ALL the time!

MS: So...Work on creating a life in which you can study while other people work. Oh, the patriarchy. The ultra-orthodox. White nationalism.

YK: Not necessarily. Your friend Ibn Paquda offers a reading on Ben Zakai that focuses less on whether you work, but on your state of mind while you work. We have to work, he says, on bringing ourselves to a state in which even when we are working, we are doing it with the consciousness of our deeper purpose.

MS: I see, so It’s not necessarily about how you use the time, but about the attitude you carry as you do whatever you’re doing. That reminds me of the way the mindfulness teachers talk about washing the dishes.

YK: If your attitude toward the fact that you have to wash the dishes, go to work, take out the garbage, treat people fairly, is indignant, betraying a sense that it has nothing to do with what you’re supposed to be doing with your time, then all of those will feel like a burden. Take for example the following Mishnah from Pirkei Avot:

“Whoever takes upon himself the yoke of the Torah, they remove from him the yoke of government and the yoke of worldly concerns, and whoever breaks off from himself the yoke of the Torah, they place upon him the yoke of government and the yoke of worldly concerns.”

Ibn Paquda teaches that the yoke of Torah ceases to feel like a burden when you accept it. Likewise, it is only when you do not accept your work as part of your purpose in this world that it feels burdensome.

MS: So, in order to spend our time well we have to let go of the resistance to whatever we’re engaged in.

YK: It’s possible the Ibn Paquda might accept that formulation. For me it’s one step deeper though. I don’t think we’re meant to completely resolve our resistance. We have to accept that we’re human beings, and we’re designed to have different forces pulling us in different directions.

MS: Work-study-pleasure-depth-Spanish soap operas.

YK: The instinct to resolve the tension between what you want to do and what you should do, what is impossible and what is possible, only makes that existential tension unbearable – and then time is wasted.

MS: When we fight against our portion in this life – including our very humanness - we suffer, and then we end up in front of the screen feeding our anxieties.

YK: When you are immersed in the kishkes of existence, the internal battles of what to do, right and wrong, worthwhile and not, you’re okay. When you try and untangle that innate part of our lives, you’re not.

MS: So an hour immersed in the kishkes of existence is one well spent.

YK: Like this conversation.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

The Jewish People?

by Rabbi Misha

In a famous exchange between Gershom Scholem and Hannah Arendt following the publication of The Banality of Evil, Scholem accused Arendt of having no love for the Jewish people.

Protesters in downtown Jerusalem, including my brother, this week. "A job in the government that costs the hostages' lives" and "Your conscience is dark"

Dear friends,

In a famous exchange between Gershom Scholem and Hannah Arendt following the publication of The Banality of Evil, Scholem accused Arendt of having no love for the Jewish people. “I have never in my life ‘loved’ some nation or collective,” Arendt answered. "The fact is that I love only my friends and am quite incapable of any other sort of love.”

Arendt’s appealing response touches on a bigger and more difficult question, which my rabbi, Jim Ponet has been asking me and many others for years: what is the Jewish people, and does it really exist? In a political landscape in which different entities claim to speak for “the Jewish people,” and others say “not in my name,” Rabbi Ponet’s question comes to life.

My friend and study partner, Yoni Kretzmer has at times suggested a radically different idea of what this people is, which follows a certain elitist strand of Medieval Jewish thinkers. Jews are those who truly follow the Torah. This would exclude vast numbers of so-called Jews, beginning with the ultra-nationalist thugs who blatantly profane every biblical law of decency to fellow human beings, even as they tout their religious garb. Jews, according to this strand of thought, are those who love others as themselves, and are committed to the constant self-examination and self-improvement that the Torah demands. According to this logic, the Jewish people, for example, could have nothing to do with a morally flawed institution such as a state, beyond perhaps being citizens of it if they happened to live in one.

However attractive this view may seem at times, there is no doubt of its vanity. The Jewish people cannot be sanitized into some ideal. Like any person, it includes beauty and filth, wisdom and ignorance, peace and war. If I have an answer to Arendt, it is that a nation is very much like an individual person. What makes a friend a friend begins with the fact that you know them well. Like it or not, we, as Jews, know the Jews. We know the loud Jews and the quiet ones, the hateful ones and the incredible ones. We know which Jews we’re like, and which we’re not like, and which Jews we like and which we don’t. Some of us end up falling on the side of friendship with the Jewish people, and others on the side of discomfort and enmity. Most of us find a way to combine the two.

I write this in the context of our preparation for the High Holidays, and my inescapable feeling that the Jewish people, more than ever before, need to make Teshuvah. We – whoever that means – are in dire need of the elements of the Days of Awe: probing self-examination. A settling of confusion through the return to the fundamental value of care. Remembering that we will die and that could happen any time. A real attempt to see how deaf, dumb and blind we have been, and the consequences this wrought upon us.

I cannot shake the thought that this Jewish people that we are a part of is in need of something new and different. A continuation feels insufficient. Even renewal feels like too soft a word. We need to begin again in some fundamental way, and we need to think deeply about what that means.

On Tuesday I began posting the daily offerings of Soul-Math, or self-examination that Rabbi Bahyah Ibn Paquda wrote in the 11th century. So far he's asked us:

How often are you in touch with the miracle of the fact of your being alive – and of your still being alive?

What is the state of your relationship with your body?

What is the state of your relationship with your mind?

What is the state of your relationship with being Jewish?

These are great questions for each of us to ponder individually. Perhaps we should think about them on a national level as well. To paraphrase his questions to a national level:

Maybe our national relationship with continued survival is all wrong?

Is something sick in our collective body?

Maybe we are feeding our collective mind garbage instead of nourishment?

Maybe we are misunderstanding what we mean when use the term “the Jewish people?”

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Soul Math

by Rabbi Misha

If you don't follow us already, HERE's how you can do it!

Tashlich on the East River last year.

Dear friends,

In the final chapter of the 11th century masterpiece, Duties of the Heart, Rabbi Bahya Ibn Paquda writes something surprising. The chapter is called The Gate of Love and is the climax of the journey through the previous nine gates, or chapters that preceded it. Love of God, as Ibn Paquda calls it, is the purpose toward which Observation, Trust, Detachment and all the other gates are set. Love is “the top of the staircase,” as he calls it. But, he warns, “whoever tries to reach it on its own will fail.” Love, he suggests, necessitates preparation.

We called our High Holidays’ theme this year Begin Again, by which we mean that we will try to bring ourselves again to a place of love. Beginnings are love. They are intrinsically hopeful. But as Ibn Paquda points out, you can’t just say you’re going to be loving and do it. It takes time, patience and hard work to allow for the presence of love to be experienced, so that a new beginning can take place.

In the Jewish tradition this work is called Teshuvah, a word which combines the two English words repentance and return. The self-examination embodied by the heavier word of the two, repentance, is the gate through which one need walk in order to experience the sweetness of the second word, return. We are welcome home, to the part of us that is all goodness and peace, only once we have looked seriously at our actions along the road – both collective and individual.

In the eighth chapter of his book, שער חשבון הנפש, the Gate of Soul Math (or Accounting of the Soul), Ibn Paquda lays out 30 types of self-examination that can lead you to seeing the truth of your existence in such a way that allows a person to proceed in their actions in the world with total ease: “Then her soul will quiet, and her thoughts will rest from the worries of the world.” Each of these 30 types, or faces as he called them, offers a question to contemplate about where you’re at, where you’ve been and where you’re going. They range from simple questions about things you might take for granted, to probing asks about the reasons you act like you do. Some deal with your conscience, others with your priorities, some with your relationship with your body, others with how you treat your mind. Here he asks about your relationship with death, there about your attitude towards money. Throughout, Ibn Paquda gently implores you to seek a more harmonious and loving relationship with that elusive essence of yourself that he calls your Neshamah, or soul.

This Wednesday the Hebrew month of Elul begins. Elul is a month-long preparation for the new year, an opportunity to self-examine on the path toward truth and love. This Elul I will follow Ibn Paquda’s 30 Faces of Soul-Math, offering a short video on Instagram each day with one of his wonderful questions. I’ll actually start on Tuesday, considered the first day of Elul even though it’s the last day of Av, since Elul only has 29 days. There’s some spiritual Jewish math for y’all to work out!

If you don't follow us already, HERE's how you can do it!

I hope you’ll join me for this soul math journey.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Ithaka

by Rabbi Misha

a timeless poem

Delphi, Greece

Dear friends,

Ithaka

By Constantine Cavafy

As you set out for Ithaka

hope your road is a long one,

full of adventure, full of discovery.

Laistrygonians, Cyclops,

angry Poseidon—don’t be afraid of them:

you’ll never find things like that on your way

as long as you keep your thoughts raised high,

as long as a rare excitement

stirs your spirit and your body.

Laistrygonians, Cyclops,

wild Poseidon—you won’t encounter them

unless you bring them along inside your soul,

unless your soul sets them up in front of you.

Hope your road is a long one.

May there be many summer mornings when,

with what pleasure, what joy,

you enter harbors you’re seeing for the first time;

may you stop at Phoenician trading stations

to buy fine things,

mother of pearl and coral, amber and ebony,

sensual perfume of every kind—

as many sensual perfumes as you can;

and may you visit many Egyptian cities

to learn and go on learning from their scholars.

Keep Ithaka always in your mind.

Arriving there is what you’re destined for.

But don’t hurry the journey at all.

Better if it lasts for years,

so you’re old by the time you reach the island,

wealthy with all you’ve gained on the way,

not expecting Ithaka to make you rich.

Ithaka gave you the marvelous journey.

Without her you wouldn't have set out.

She has nothing left to give you now.

And if you find her poor, Ithaka won’t have fooled you.

Wise as you will have become, so full of experience,

you’ll have understood by then what these Ithakas mean.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Why Did She Descend?

by Rabbi Misha

For a couple of weeks I couldn’t get this one Hasidic niggun out of my head...

Mipney Ma, a Hassidic niggun by Frank London

Dear friends,

For a couple of weeks I couldn’t get this one Hasidic niggun out of my head:

מפני מה ירדה הנשמה?

Why did the neshamah fall so low?

מאיגרא רמא לבירא עמיקתא

From a high roof to the bottom of a deep well.

I listened to Frank London’s beautiful version of the niggun, sang it and played it on my saxophone. I wondered why things have sunk so low. I’d think of the endless horror in Gaza, of the never-ending tribulations of my Israeli family and friends, of the horrors of this world we live in and the terrible state of affairs between people of different opinions in the US. Why? Mipney ma?

Then the niggun would come to its concluding C part, from the ancient wisdom:

ירידה לצורך עליה היא

It’s a descent for the purpose of going up!

The universe is not static. Everything is in motion. Oftentimes things go down and then up, up and then down. Why would we expect our experience to be any different? I would pray that this descent is part of a rising. That Frank’s cancer for which he’s being treated will be part of a rising up that will help him heal and grow. That from global warming we will learn simplicity, contentment with what we have. That out of this war will grow peace.

Yesterday a miracle happened. Despite terrible odds, flight cancellations, threats of an even worse war, despicable war-mongering provocations by the Israeli government and its morally bankrupt leader, my family managed to meet for a few days in Greece to celebrate my father’s 75th birthday. Thanks to the grace of god, ours and the many that populate this divine land, my parents, brothers and their families from in and around Jerusalem managed to get here. The long odds have certainly created a deep sense of gratitude in us. We are in a little moment of עליה, going high up.

May the current talks in Doha bring us further up, to a ceasefire. It is not lost on any of us that families in Gaza could never imagine such a reunion. For so many families it is no longer possible. Prayers can sometimes alter reality. Let us pray that a breakthrough is reached, and that this latest escalation was a descent for the purpose of going up. Hostages home, leadership change, reconstruction begin - not one more bomb. Let families reunite all over the land.

And may we see all of the descents of our souls turn into miraculous rising ups.

Why? Mipney ma? So we can experience the great gift.

Shabbat shalom with prayers of gratitude,

Rabbi Misha

Sunrise over Athens

Transforming Hate

by Rabbi Misha

For a couple of weeks I couldn’t get this one Hasidic niggun out of my head...

Dear friends,

a Meditation for Tisha B’Av.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

A Prayer for Safety

by Rabbi Misha

Pray for the peace of Jerusalem:

Nachlaot, Jerusalem

Dear friends,

Pray for the peace of Jerusalem:

“May those who love you enjoy tranquility.

And let there be peace within your walls.”

For my family, for my friends

I say, “Peace be within you.”

For our home, for our hearts

I ask, "Goodness direct you."

Psalms 122

שַׁאֲלוּ, שְׁלוֹם יְרוּשָׁלִָם; יִשְׁלָיוּ, אֹהֲבָיִךְ.

יְהִי-שָׁלוֹם בְּחֵילֵךְ; שַׁלְוָה, בְּאַרְמְנוֹתָיִך

לְמַעַן, אַחַי וְרֵעָי-- אֲדַבְּרָה-נָּא שָׁלוֹם בָּךְ.

לְמַעַן, בֵּית-יְהוָה אֱלֹהֵינוּ-- אֲבַקְשָׁה טוֹב לָךְ.

May Israelis be safe this Shabbat, as they wonder when the attack will begin. May Palestinians be safe this Jum'ah, as they try to avoid the next bombing. May they all be disentangled from the web their leaders have caught them in. And may all who love the holy city find rest.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Soul Ancestor

by Rabbi Misha

As the world jumps up and down, throwing my heart around, grabbing at my attention with all its sparkling might...

The Tree and the Rock

Dear friends,

As the world jumps up and down, throwing my heart around, grabbing at my attention with all its sparkling might, I have been finding great comfort in returning to the unchanging, steady truth found in a 1000-year-old book. It was written in Arabic in the south of Spain by a person we know very little about. We’re not even sure how to pronounce his name, בחיי, which could be read Bahyey, Bahya, Behayai to name a few options. We know his family name was Ibn Paquda, the son of Paquda, and from an acrostic poem he left we know also that his father’s name was Yosef. We know he was a rabbi, and a Dayan, a judge in courts of Jewish law. And then we have his book, The Duties of the Heart, which is beloved canonical book that reveals to us more about his true self than any external details could reveal. It opens for us the gates to this beautiful man’s mind, heart and soul.

The central premise of the book is that our precious time on earth should be divided between two types of duties: those of the limbs, which we complete with our bodies, and the duties of the heart. Yes, he says, there are 613 commandments in the Torah, which have been expounded and expanded in the Talmud into thousands of Jewish laws. But the constant calls of our conscience and heart, which remain unseen and hidden to others, the revealed laws of the tradition are just a small fraction of our purpose.

The period in Jewish history when Ibn Paquda lived, when for a few hundred years in the Middle Ages the Jews were living in relative peace in Spain, was arguably the greatest time to be a Jew. The most important Jewish books of philosophy, theology, mysticism and poetry all come from there. You can feel in the writing the influences of the great Muslim thinkers, as well as the centrality of Plato and other Greek thinkers, of Andalusian music and spirit.

Ibn Paquda’s book is an overflow of his time period. It is a socio-theological treatise of philosophical inquiry, whose surprising poetry combines mystical leanings with scientific knowledge. It offers the reader ten gates to walk through, in order to connect with and bring harmony to your soul; a guide to the neshamah to make good use of its time in life.

Occasionally Ibn Paquda address the reader: אחי, he calls us, “my brother.” He offers us - his soul-siblings - loving encouragement on the path through the ten gates. The presence of the true self, this part of us that transcends time and place, is what gives you the sense that you know, really and truly, this generous ancestor whose heart stopped beating 904 years ago.

After he completes his journey through the ten gates, (some of which I hope to write about in the coming weeks) ending, naturally, with love, he leaves us with several pages of Hebrew poetry. Two of these final pages are addressed directly to the soul. Here a few lines, hastily translated from the rhyming poem he addresses to his soul:

נפשי. עוז תדרכי. וצורך ברכי. וחין לפניו תערכי. ושיחה לנגדו שפכי. והתעוררי משנתכי. והתבונני מקומכי. אי מזה באת ואנה תלכי:

My soul,

Find the courage to be strong, and bless your Rock.

Direct yourself toward grace, and

Pour your heart out.

Wake up from your slumber

and look around,

Notice: you are here!

Where have you come from?

Where will you go?

והחיים והמות אחים. שבתם יחד איש באחיו ידבקו. יתלכדו ולא יתפרדו. אחוזים בשתי קצות גשר רעוע. וכל ברואי תבל עוברים עליו. החיים מובאו והמות מוצאו. החיים בונה והמות סותר. החיים זורע והמות קוצר. החיים נוטע והמות עוקר. החיים מחביר והמות מפריד. החיים מחריז והמות מפזר.

Life and death are brothers.

They sit together, clinging to one another.

Each of them holds an end of

that rickety bridge

which all creations walk over: its origin, life, its end, death.

Life builds; death undoes.

Life sows; death reaps.

Life plants; death uproots.

Life connects; death separates.

Life rhymes; death scatters.

בקשי צדק בקשי ענוה. אולי תסתרי ביום אף יי. וביום חרון אפו. ותזהירי כזהר הרקיע וכצאת השמש בגבורתו. ותזריח עליך שמש צדקה ומרפא בכנפיה. ועתה קומי לכי והתחנני לאדוניך. ושאי זמרה לאלהיך.

Seek justice, seek humility,

So you have a chance of surviving those days of wrath,

So the gentle sun will shine its healing rays upon you.

Now

Stand up,

Start walking.

Make yourself a vessel of graciousness,

and lift a song up

Toward your god.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

The Cultivation of Beauty

by Rabbi Misha

“Would you kill a baby chicken for a billion dollars?” This was the question Manu posed to me as part of our morning prayers today. My heavy-handed response that followed was a reflection of the troubling effect this week’s events had on my soul. “Do you know what a sin is,” I recall myself asking. “No,” said my seven-year-old.

Dear friends,

“Would you kill a baby chicken for a billion dollars?” This was the question Manu posed to me as part of our morning prayers today. My heavy-handed response that followed was a reflection of the troubling effect this week’s events had on my soul. “Do you know what a sin is,” I recall myself asking. “No,” said my seven-year-old. “Killing for the sake of killing is a good example of it.”

We still don’t know why Thomas Matthew Crooks pulled the trigger. But that fact is one of the most chilling pieces of this last week. At this point it appears as though there was no ideological drive. Evidence from his phone suggests that he may have been considering shooting Biden or Trump. Either one would do. If you haven’t read Michelle Goldberg’s piece in the Times this week, it’s worth it. She describes an online world where young men encourage one another to commit acts of violence for the sake of violence. This sad vacuousness of meaning and purpose, out of which this thinking emerges, is our greatest enemy.

We see this despairing, dark attitude all over the world. It shouldn’t surprise you that this is the meaning of the biblical word Hamas, one of the world’s greatest examples of violence for the sake of violence. In the bible, a person of חמס (Hamas) is one whose worldview is violence. In this lawless world, this person thinks, violence is the only appropriate, even the holy way to act. It’s sad to witness many of my fellow Israelis fall down this same path. The rifle used to mean something very different to Jews than it does today. That’s true about Americans too, and many others. It has become in large part a symbol of the incurable, lonely emptiness of life.

Isaiah’s prophetic sense could see that clearly when he said:

“and they shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruninghooks.”

My prayerful conversation with Manu took place in my parents in law’s gorgeous garden in Montreal. My father-in-law, Roby is a master gardener who spends much of the warm months (which now get very hot!) creating and tending his garden. Every year the flower arrangements are different. Perennials mix with annuals to create a dazzling corner of Eden.

When Manu and I discussed what we’d like to say wow about this morning (our version of what the traditional prayers call praise), several different specific flowers nearby were mentioned, as well as the Apple tree over a bed of day lillies. When we were done, I told Roby that I’m thinking of writing about his garden as the antidote to the world’s ills. “That’s true,” he said, “but not looking at it – working in it.”

It’s not enough just to see the ephemeral beauty. If we want to feel the beauty, we have to work on our garden. Thankfully, Shabbat is almost here, so for now we can just take it in with our eyes. But we better get our gardening gloves ready for Monday morning.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

The Value of Surrender

by Rabbi Misha

In the upside down ways of the world, people want to win. “Total victory,” says one leader, "I didn’t lose, I won big,” says another.

Dear friends,

In the upside down ways of the world, people want to win. “Total victory,” says one leader, "I didn’t lose, I won big,” says another. These are reflections of us and our battles with reality. An attitude that might be more attuned to the deeper truth of our existence is that the desire to win is a mis-formulation of the mind. Instead, we might consider the value of surrender.

“The Gate of Surrender” is the title of the sixth chapter of Rabbi Bahyeh Ibn Pekuda’s eleventh century masterpiece, Duties of the Heart. Reading it is a balm to the ridiculous vanity of our times.

Pekuda describes a person who acts with the value of surrender: “a soft tongue, a low voice, humility at a time of anger, not exacting revenge when one has the power to do so.”

How different would our world be if we all acted with humility at times of anger? How different would our family lives be, our friendships, our relationships with our national and personal neighbors?

Today, one of the worst sources of pride-infused certainty is religion. I guess things weren’t so different a thousand years ago, since the God-touting person’s destructive pride is what led Pakuda to write this chapter:

“...arrogance in the acts devoted to G-d was found to seize the person more swiftly than any other potential damager. Its damage to these acts is so great that I deemed it pressing to discuss that which will distance arrogance from man, namely, surrender.”

Of course, people spouting their righteous anger are not exclusively religious. As a matter of fact, when secular people speak passionately about the horrors they see in the world, and about the justice they fight for, they most often do it with the same religious fervor that people of faith do. Almost everyone these days seems to need to work hard against arrogance:

“...to distance a person from the grandiose, from presumption, pride, haughtiness, thinking highly of oneself, desire for dominion over others, lust to control everything, coveting what is above one, and similar outgrowths of arrogance.”

Surrendering to the deeper reality of our humanness helps.

“One of the wise men would say on this matter: "I am amazed at how one who has passed through the pathway of urine and blood two times (once as semen, the other as a newborn) can be proud and haughty?"

We could continue fighting death for as long as we want. We won’t win. We could continue fighting what is for as long as we want. We won’t win. Accepting this can make the work of improving the lives we live and the world we live in not only more pleasant, but also more effective.

“...for one whom arrogance and pride have entered in him, the entire world and everything in it is not enough for his needs due to his inflated heart and due to his looking down with contempt on the portion allotted to him. But if he is humble, he does not consider himself as having any special merit, and so whatever he attains of the world's goods, he is satisfied with it for his sustenance and other needs. This will bring him peace of mind and minimize his anxiety. But for the arrogant - the entire world will not satisfy his lacking, due to the pride of his heart and arrogance, as the wise man said (Proverbs 13): "A righteous man eats and is full, but the stomach of the wicked never feels full."

צַדִּיק אֹכֵל לְשֹׂבַע נַפְשׁוֹ וּבֶטֶן רְשָׁעִים תֶּחְסָר.

If anything will lead us to victory it is surrender. I pray for acceptance, for gentleness, for the ability to move forward toward goodness with simplicity and truth.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Clear and Present Danger

by Rabbi Misha

Please forgive me in advance for stepping out this week of my rabbinic frame of mind and inhabiting my position as a concerned Israeli living in the US. I won’t be invoking the tradition today, which means I won’t be talking about morality, humanity, responsibility and love.

Israeli-Palestinian peace conference in the Menora Arena calling for an end to the war and a solution to the conflict, Tel Aviv, July 1, 2024. (Photo, Oren Ziv)

Dear friends,

Please forgive me in advance for stepping out this week of my rabbinic frame of mind and inhabiting my position as a concerned Israeli living in the US. I won’t be invoking the tradition today, which means I won’t be talking about morality, humanity, responsibility and love. I won’t be writing about the horrific realities of this war on Palestinians, which we all need to name and face. I won’t be talking about Hamas. I won’t be writing about America. Today, I will simply be writing about the Jews of Israel and the very real danger they are in.

“Hamas’ new response to the offer of the mediators in the negotiations sparked deep disagreements between the PM, Benjamin Netanyahu and all the heads of the security forces.” This line, published yesterday by Amos Harel, one of Israel’s leading military analysts, captures much about the current state of affairs in Israel. Netanyahu is one of the few people still in favor of continuing the war. He seems to be working to scuttle the agreement to release the hostages, while all of the leaders of security forces want this deal. All of them. These are not soft people. They are not dreamers. They are hardened generals and heads of intelligence operations who are meant to protect the country. This is because they see a real and immediate danger to the country if this war continues.

Alarm bells have been ringing for many months. More and more voices in Israel have been calling for de-escalation. Op-eds came out in the last month by two former Israeli Prime Ministers with titles like “We Are in a True Emergency Situation. We Must Lay Siege to the Knesset and Bring Down this Government.” This from a former Ehud Barak, the former IDF Chief of Staff, Minister of Defense and Prime Minister. Ehud Olmert, another former Prime Minister, who spent most of his career in Netanyahu’s Likud party, recently wrote: “Netanyahu wants Israel’s destruction. No Less.”

What is that clear and present danger? There are many dangers, but the leading one is a second war in Lebanon. Yesterday, over 2000 rockets were fired at Israel from Hizballah. 2000 rockets! If they start using their longer-range missiles, they could destroy Tel Aviv. Hizballah is likely to use those missiles if and when Israel launches a ground offensive. Netanyahu seems intent on doing that despite clear signs from Hizballah that it will stop attacking if a truce is reached in Gaza.

This week I heard Amira Hass speak. Amira has been writing for Haaretz for decades and is a unique voice among Israeli and Palestinian journalists. The daughter of two Holocaust survivors, she lived in Gaza for several years, and today she lives in Ramallah. She knows the Palestinian viewpoint from the inside, as well as the Israeli one. Her message this week: You should be deeply concerned about the possibility of huge numbers of Jews being killed in Israel, that will make October 7th seem minor, because the leaders of the Jewish community of Israel are creating conditions that can easily lead to another catastrophe. To prevent this, we need to apply very real pressure on Israel’s government to make a deal and end this war.

I don’t know who still supports this war. It has brought back seven hostages (all the others came back through a negotiated deal) and killed dozens of them, if not more.

In the first four days of July, it has claimed the lives of the following Israeli soldiers:

20 year old Eyal Mimran, killed in Sheja’iya

21 year old Roy Miller, killed in Northern Gaza.

21 year old Elay Elisha Lugassi, killed in Northern Gaza.

38 year old Itai Galea, killed in the Golan Heights.

19 year old Alexander Yekiminsky, killed in a stabbing in the Galilean city of Karmiel.

25 year old Eyal Avniyon, killed in Central Gaza.

30 year old Nadav Elchanan Noler, killed in Central Gaza.

22 year old Yehudah Getto, killed in Tul Karem in the West Bank.

21 year old Uri Yitzhak Hadad, killed in Southern Gaza.

These are Netanyahu’s dead. Yehi Zichram Baruch.

And if you’re asking yourself, what does Misha want from me? What can I do over here? First and foremost, tell your representatives that Netanyahu’s visit to congress is an abomination. Next, remove your support from any organization that blindly supports the Israeli government. I believe these organizations put Israelis in grave danger. Instead, support one of the dozens of organizations that miraculously managed to bring about the largest gathering in Israel for peace in decades, like NIF or Standing Together. My friends and family back home suffer from a far deeper despair and agony than us here. And yet, despite unreal police violence, threats from fanatics, mockery by much of the country and a history of physical assault and even murder of anti-war activists, they continue to go out into the streets to demand change. A rising up is taking place there. Let’s take our cue from the six thousand pro-peace Israelis who came together in Tel Aviv to say End This War.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

But who told me to try to understand?

by Rabbi Misha

In honor of the arrival of summer, two Iberian poems to drive us out of the never-fading anxiousness about the state of the world and into the plain reality of this beautiful season:

Kaitz Niggun (Summer Melody) by Yonatan Gutfeld

Dear friends,

In honor of the arrival of summer, two Iberian poems to drive us out of the never-fading anxiousness about the state of the world and into the plain reality of this beautiful season:

From The Keeper of Sheep by Alberto Caiera (One of the pseudonyms of Portuguase poet Fernando Pesoa)

XXII

As when a man opens his front door on a summer day

And gazes with full face upon the heat of the fields,

Sometimes Nature suddenly hits me smack

In the face of my five senses,

And I get confused, mixed up, trying to understand

I don't know quite what, or how.....

But who told me to try to understand?

Who said there's something to be understood?

When summer passes the soft warm hand

Of its breeze across my face,

I need only feel the pleasure of it being a breeze

Or feel the displeasure because it's warm,

And however I may feel it,

Because that's how I feel it, is what it means to feels it.

The Silence, by Federico Garcia Lorca

Listen, my son: the silence.

It's a rolling silence,

a silence

where valleys and echoes slip,

and it bends foreheads

down towards the ground.

(or in the original Spanish)

El Silencio

Oye, hijo mio, el silencio.

Es un silencio ondulado.

un silencio,

donde resbalan valles y ecos

y que inclina las frentes

hacia el suelo.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

We Must Imagine Job Happy

by Rabbi Misha

As somehow always happens when you study the Book of Job, we ended up chewing on Job’s final words. We were already in hour three or four of our wonderful Tikkun Leil Shavuot this week, which focused on Job, when the words were spoken:

Sam's Point, Minnewaska State Park

Dear friends,

As somehow always happens when you study the Book of Job, we ended up chewing on Job’s final words. We were already in hour three or four of our wonderful Tikkun Leil Shavuot this week, which focused on Job, when the words were spoken:

"לְשֵׁמַע אֹזֶן שְׁמַעְתִּיךָ, וְעַתָּה - עֵינִי רָאָתְךָ, עַל כֵּן אֶמְאַס וְנִחַמְתִּי עַל עָפָר וָאֵפֶר"

Job has lost everything he had, sat silently in his devastation for a week, offered lament after lament. He has heard four of his friends try and talk some good religious sense into him, and then heard God’s voice unleash sweet poetry, that reminds Job of the exquisite beauty of the world. And then we reach this line. I’ve read it hundreds of times in Hebrew, read many different translations of it, translated in myself a few times, heard other translations, argued over it, studied it - but its meaning remains elusive.

The first half of the verse is easier - “I had heard about you with my ears; but now my eyes have seen you.” Stephen Mitchell’s translation stays true to the Hebrew in this case. And all the translators and commentators agree that Job is saying something like that. It’s the second half of the verse that’s harder to grasp. Even when you go word by word and understand each piece of the sentence, somehow by the time you’ve reached the end of it you still aren’t sure what he’s saying.

על כן means “therefore.”

אמאס means something like “I’m sick of it” in modern Hebrew, or “I’ve grown to detest” in some biblical passages, a type of abandoning of an idea or a person or God in others. It is the hardest word to translate in the sentence.

וְנִחַמְתִּי means “I am comforted.”

ּ עַל עָפָר וָאֵפֶר means “over dust and ashes.”

All together it would be something like: “therefore I’m sick of it, and I am comforted over dust and ashes.” Which doesn’t make much sense. Mitchell offers: “Therefore I will be quiet, comforted that I am dust.” Raymond Scheindlin suggests: “I retract. I even take comfort for dust and ashes.” As you see, that word אמאס can really be interpreted very differently. Edward Greenstein translates the first half of the sentence “that is why I’m fed up.” King James goes: “Wherefore I abhor myself.”

My rabbi, Jim Ponet used to make a classic rabbinical exegetical move and say that the written word אמאס should actually be understood like another Hebrew word that sounds almost identical, אמס, which means “I melt.” The suggestion is that Job’s final words are a total softening, a renunciation of anything and everything he previously believed and argued, a type of acknowledgement of the emptiness, in the Buddhist vein. His acceptance of what has happened to him comes in the form of losing his mind’s previous form. But in recent years Rabbi Jim’s seemed to have moved on from that understanding.

It was his son, David who in our Tikkun opened up a new vista on the verse for me. David, the School for Creative Judaism’s Philosopher in Residence, brought in some text from Camus’ The Myth of Sisyphus. Sisyphus is another mythological Job-like character, punished pretty severely: he has to push that huge rock up the mountain over and over again for eternity, watch it roll down and start again. Camus opens his book by asking all of us Sisyphi: how come we don’t kill ourselves, much like Job’s wife asks him in the second chapter of Job. But by the end of his book, he’s managed to embrace the absurdity of the human situation and even find freedom in it. Sisyphus pushes that rock up the mountain. It falls down to the bottom. Sisyphus turns to walk down the mountain again.

“It is during that return, that pause, that Sisyphus interests me,” Camus writes. “That hour, like a breathing space that returns as surely as his suffering, that is the hour of consciousness.” He imagines him walking down the hill. “If the descent is sometimes performed in sorrow, it can also take place in joy.” In other words, while Sisyphus walks down the mountain to begin pushing that huge rock up again, he might be HAPPY. Is he overstating it? “This word is not too much,” he tells us.

Camus’ final lines are some of his most famous, and probably his most ecstatic:

“This universe henceforth without a master seems to him neither sterile nor futile. Each atom of that stone, each mineral flake of that night-filled mountain, in itself, forms a world. The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man's heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy."

And so I ask myself – might one imagine Job happy as well?

I don’t think that’s possible for most of the book. Even Sisyphus' imagined happiness is focused more on the empty pause when he's walking down the hill than on the painful pushing of the rock uphill. Job's arguments with his friends and God are the equivalent of pushing the rock up the mountain. The question is whether at the end, in the 42nd chapter, when he speaks his last lines, we can imagine him happy. Remember, this is before God announces that he was right all along, and before he gets everything he had at the beginning back twofold. For Job “the hour of consciousness” must be that moment during which says:

“I had heard about you with my ears; but now my eyes have seen you."

We must imagine Job happy when he says these words. His “comfort over dust and ashes” must be a warm and beautiful sentiment. He has made peace with death, and in so doing he has made peace with life. That elusive word, אמאס, must be part of that process of finding joy. At the Tikkun I thought maybe it means: “I give up. I raise the white flag. I surrender. No more war. No more fighting. No more demanding that reality conform to my needs. I am now ready to experience comfort, to sit in what is.”

So for today, this Shabbat, I raise the white flag. I give up on trying to understand the best translation of this verse. I give up on understanding, on insisting that this world be different than it is. Instead, I imagine myself happy, surrounded by the sweet-scented summer air, resting in the gift of Shabbat.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

The Cuckoo's Punishment

by Rabbi Misha

Amazingly in synch with the times, this Shabbat’s parashah deals with reward and punishment.

Dear friends,

Amazingly in synch with the times, this Shabbat’s parashah deals with reward and punishment. Sixteenth century Rabbi Yaakov Ben Yitzhak Ashkenazi writes:

The Holy One said: I have said that I properly pay each one according to their deeds, so how is it that an evildoer is very rich? Concerning this, the Holy One responds that the wealth of the evildoer, when he gathers wealth through theft or usury, it does not remain long. A bird called a partridge, sits on the eggs of other birds and incubates them. When the birds hatch from these eggs, they do not follow this bird, but they leave and follow their own. So too is the wealth of the evildoer. Similarly, when he has lots of money it will not remain with him for long. The wealth must depart during his lifetime and in the end he will be left a wretch.

The rabbi was working on the following verse in this week’s Haftarah:

קֹרֵ֤א דָגַר֙ וְלֹ֣א יָלָ֔ד עֹ֥שֶׂה עֹ֖שֶׁר וְלֹ֣א בְמִשְׁפָּ֑ט בַּחֲצִ֤י יָמָו֙ יַעַזְבֶ֔נּוּ וּבְאַחֲרִית֖וֹ יִהְיֶ֥ה נָבָֽל׃

Like a partridge hatching what she did not lay

So are those who amass wealth by unjust means;

In mid-life it will leave them,

And in the end they will be proved fools.

In the 11th century, Rashi explained this bird bahavior a little bit differently:

This cuckoo draws after it chicks that it did not lay. דָגָר (the second word in the verse)- This is the chirping which the bird chirps with its voice to draw the chicks after it, but those whom the cuckoo called will not follow it when they grow up for they are not of its kind. So is one who gathers riches but not by right.

Steinsaltz, in the 20th century offered yet a different bird bahavior:

A partridge, a small wild bird from the pheasant family, collects and tries to incubate eggs that it did not lay. When several of these birds share a nest, there is often a struggle between them, with each trying to expel the others and gather all of their eggs under its own wings. Since the partridge’s wings are fairly short, it cannot protect and properly incubate the stolen eggs, many of which are ultimately ruined or abandoned. This is a metaphor for a dishonest person, one who amasses wealth unjustly. Just as the partridge does not benefit from the eggs it stole from others, so too such an individual will not profit from his wealth. In the middle of his days he will leave it, and at his end he will be reviled, disgraced, and wretched, or, alternatively, he will be revealed and recognized as a wicked criminal.

19th century Malbim had a different view, not of the bird's bahavior but of the thief’s punishment. While he may lose his money, he’ll never lose the terrible nature he adopted.

באחרית ימיו יהיה עוד גרוע ממי שלא היה לו עושר כלל, שהגם שלא היה עשיר מימיו לא היה נבל אבל הוא ישאר נבל, כי ישאר בו הטבע לעשוק ולחמוס ולעשות נבלה

In his old age he will be worse off than one who never had any wealth, since the one who was never rich was also never a scoundrel – but he will stay a scoundrel, because the instinct to oppress, be violent and spread corruption will never leave him.

No matter how exactly this bird metaphor is supposed to work, and what a partridge actually does with the eggs or the chicks that it steals, eventually, says the prophet, truth will manifest, and even the king’s nakedness will be revealed.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Truly Letting Go

by Rabbi Misha

An interview with Authentic Movement teacher, Eileen Shulman

Mystical artwork by Danielle Alhassid, piano Damian Olsen

Dear friends,

An interview with Authentic Movement teacher, Eileen Shulman

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Time to Break it

by Rabbi Misha

There come times when the only thing to do is to break the rules; to go against the foundational principles; to do the exact opposite of what you always believed to be right. Is this one of those times?

Mystical artwork by Danielle Alhassid, piano Damian Olsen

Dear friends,

There come times when the only thing to do is to break the rules; to go against the foundational principles; to do the exact opposite of what you always believed to be right. Is this one of those times? The world seems in bad enough shape to warrant a shakeup. Tomorrow night we will harken back almost two thousand years to a time when the human situation was so bad that ten mystics decided that the only way to heal was to break the most foundational laws, the pillars on which our entire faith stands.

עת לעשות ליהוה הפרו תורתך, they declared,

It is time to do for God – so break the Torah!

This is the first verse quoted by Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai in what is called the Great Gathering, or the Idra Raba, a wildly poetic segment of the Zohar which we will delve into tomorrow. It describes a nighttime rabbinical retreat to the forest designed to alter the spiritual position of the divine realm, during a time of continuous wars and real threat to the continued survival of Judaism.

Bar Yochai’s reading of the verse is, of course, subversive. The line from Psalms is usually understood differently: “It is time do for God – for they have broken your Torah!” But Bar Yochai builds on the earlier subversive sages of the Talmud who suggested switching one vowel in the sentence to another to twist scripture into a new meaning. HEferu becomes HAferu, and thus turns the verb “to break or undo” from third person plural past tense (they have broken) to second person plural imperative (Break!).

This begins the process of taking the worst offense in our faith – giving form to the formless abstraction we call God – and turning that offense into a divine commandment. In this transgressive story, the rabbis understand that the way to realign the divine world, which will then flow into humanity, is to paint into existence the face of God. Their method is poetic exegesis: they take biblical verses to create an image of God’s face: skull, brain, eyes, nose, ears, beard. Then they chart how each facial element relates to the millions of worlds and planets and realities of our world.

While they’re at it, they decide to break down the next holy cow, the notion of one God. Once the God of Compassion is established, they paint the face of a second God – the God of Judgement. And once he is completed, they paint the Goddess. Finally, they unite the three through the poetry of love, and bring harmony back into the universe.

There are countless levels on which we stand to learn from this psychedelic mystical recounting. The act of intervening in the flow of the universe denotes a belief in human power that we have lost. The method of intervening, which combines faith, art and knowledge with a political intention is very different to the ways we have been fumbling about trying to change things. The courage to smash our holy structures in order to allow for a new flow is key to the release that a new reality would demand.

The Zohar is notoriously difficult to grasp. It needs to be invited into your senses. So the pieces of text we chose for our final Kumah event tomorrow night will both be explained by Rabbi Abby and me during the event, and, more importantly, accompanied by music and art. We will be joined by pianist Damian Olsen, performance artist Danielle Alhassid and vocalist Chanan Ben Simon. Much like the Idra Raba itself, we will proceed through structured improvisation to produce the beauty and wonder which we hope will afford a smooth internal and external flow between us and the source of all.

Join us tomorrow night at the 14th Street Y to break down the structures of reality and use the shards of that reality to paint a new world into existence.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Rise Up and Hope

by Rabbi Misha

War engenders despair. It gets in your head and speaks about your meaninglessness and powerlessness. It kills people as a means of killing hope. Which never works. Like life, hope continues.

Our hosts Steff and Ronnie at the Gotham Depot Moto, where we open the Kumah Festival this evening.

Dear friends,

War engenders despair. It gets in your head and speaks about your meaninglessness and powerlessness. It kills people as a means of killing hope. Which never works. Like life, hope continues.

Our Kumah Festival this year, which begins tonight, is a path to hope, a reminder of our ability to rise above the noise and rise up over obstacles of displacement, oppression, hatred and loss.

We begin this evening with the devotional music of the Jews of Turkey, who found refuge from the blood-thirsty Catholics of Spain not only in the lands of the Ottoman Empire, but also in its music. They countered despair with delight, death with poetry, wickedness with neighborly love. We will attempt the same with the music of East of the River, the food of Chef Sami Katz and the incredible motorcycle-filled space at Gotham Moto Depot.

Then on Sunday we will come back to the present with the Joint Israeli-Palestinian Memorial Ceremony. This is a sad gathering, there’s no doubt. But the beauty that comes every year out of the honest sharing of grief of those who are meant to be enemies is an antidote to any of the words of the sad excuse for politicians that we are used to hearing on these topics. Sharing sorrow, bringing hope, as the Bereaved Parents Circle, one of the leading organizations calls it.

The final two events on Thursday and next Saturday will approach the question of hope through two of the ancient ways human beings have used to stay focused on the right and the good: theater and mysticism. I am sure that this series of events will give us a lot of perspective, strength and energy to dive back into the burning task of ending this war and preventing the next.

See you tonight among the motorcycles!

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Real Peace

by Rabbi Misha

When the Holy Blessed One came to create Adam the first human, the ministering angels divided into various factions.

Daphna Mor and the musicians of East of the River will open our Kumah Festival on May 10th.

Dear friends,

When the Holy Blessed One came to create Adam the first human, the ministering angels divided into various factions. Some of them were saying: ‘Let him not be created,’ and some of them were saying: ‘Let him be created.’ This is what is referenced in the Psalms when it is written: “Kindness and truth met; righteousness and peace touched” (Psalms 85:11). Kindness said: ‘Let him be created, as he performs acts of kindness.’ Truth said: ‘Let him not be created, as he is all full of lies.’ Righteousness said: ‘Let him be created, as he performs acts of righteousness.’ Peace said: ‘Let him not be created, as he is all full of discord.’ What did the Holy Blessed One do? He took Truth and cast it down to earth, as is written: “You cast truth down to the earth.” (Daniel 8:12). The ministering angels said before the Holy Blessed One: ‘Master of the universe, what are you doing?! Let Truth rise up from the earth!’ As is written: “Truth will spring from the earth” (Psalms 85:12).

While the ministering angels were busy arguing with one another the Holy blessed One created Adam. He said to them: ‘Why are you deliberating? Adam has already been created.’

So much of the essence of the events of the last week are captured in this ancient midrash. Like the angels, we are passionately arguing over humanity, over Israel, while reality keeps flowing. From our American island we yell and scream, while in Gaza the madness is not theoretical. Hirsh cries out to us waving his mutilated arm. The Israeli Minister of Finance demands “total annihilation,” while the tanks line up on the border, and the two men leading this rabid tango continue to display their sick selfishness.

Last week I had a moment of pride, when Rabbi Abby joined other Jews, American and Israeli to try to deliver food to Gaza. They were stopped a couple kilometers from the border crossing, but for a moment the hollow words from the Seder: “Let all who are hungry come and eat,” were given some depth when Abby and the other Rabbis for Ceasefire spoke about the hunger across that border.

The truth is I’m hungry. Hungry for quiet, for humility, for a world that doesn’t constantly provoke the earth to spew us out. Nachmanides said that the difference between the land of Israel and anywhere else is that unlike other places, Israel vomits away the people who defile it through moral abominations. I’m not sure that’s only true of Israel.

Monday is Holocaust Remembrance Day, the day on which we recall when the Jews paid the price for the moral abomination called Europe. We are still recovering from that. Even 79 years after that war ended there are still close to one million less Jews in the world than there were in 1939. Each antisemitic chant pushes us further away from recovery. And each Palestinian child who dies too.

This week’s Haftarah is one of the clearest ethical rebukes of a nation, in a bible full of them. Speaking to Jerusalem, “the city of blood,” the prophet Ezekiel enumerates the moral, social and religious abominations of the Jews of the city – which he already knows will lead to the land spewing them out.

הִנֵּה֙ נְשִׂיאֵ֣י יִשְׂרָאֵ֔ל אִ֥ישׁ לִזְרֹע֖וֹ הָ֣יוּ בָ֑ךְ לְמַ֖עַן שְׁפׇךְ־דָּֽם׃

Every one of the leaders of Israel in your midst uses their strength for the shedding of blood.

The punishment is coming, says the prophet, the circle is coming around, and he urges the people to consider their frailty:

הֲיַעֲמֹ֤ד לִבֵּךְ֙ אִם־תֶּחֱזַ֣קְנָה יָדַ֔יִךְ לַיָּמִ֕ים אֲשֶׁ֥ר אֲנִ֖י עֹשֶׂ֣ה אוֹתָ֑ךְ אֲנִ֥י יְהֹוָ֖ה דִּבַּ֥רְתִּי וְעָשִֽׂיתִי׃

Will your heart be able to stand it? Will your hands still hold any strength in the days when I deal with you? Unlike you, I, YHVH, am not all talk.

Our fate, suggests the prophet is not sealed. Goodness could appear in a flash; as quick as regret, as sudden as a realization; “a flash of lightning,” as Nietzsche put it:

"Rendering oneself unarmed when one had been the best armed, out of a height of feeling – that is the means to real peace, which must always rest on a peace of mind; whereas the so-called armed peace, as it now exists in all countries, is the absence of peace of mind."

When our ancestors were kicked out of Spain they found refuge in Turkey. While their leaders debated how to stay alive - like the angels in the Midrash - the musicians offered peace of mind through the new music they encountered there. They were alive, they were singing, they were at peace. As we prepare to open our Kumah Festival next Friday with that very music, let the memory of the six million remind us who we are: a nation of wandering improvisors, whose weapon and saving grace has always been our imaginative mind. May we return to it and find a real peace.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Festival of Faces

by Rabbi Misha

In the second century in Palestine, after the failed Bar Kochva rebellion, the Roman Emperor Adrianus imposed harsh laws on the Jews that included forbidding the practice of the religion.

Dear friends,

In the second century in Palestine, after the failed Bar Kochva rebellion, the Roman Emperor Adrianus imposed harsh laws on the Jews that included forbidding the practice of the religion. Many Jews were killed in the decades leading up to these decrees and many more will perish. in the midst of the struggle, 10 rabbis left their dwelling in the Galilee and went into the forest at night. They needed to shift the spiritual gravity center of the world, which was off in dangerous ways. They saw how people were not seeing one other. They would look one another in the face and see nothing. The problem, the rabbis understood, stemmed from the same thing happening in the divine world. The two faces of the divine, the male and the female, the God and the goddess turned away from each other. If they could turn them to face one another, the realignment in our world would be felt, and people would once again be able to see one another’s faces.

Our world today seems to be suffering from a similar problem. Too many people are caught in frameworks of thinking that prevent them from seeing the simple humanity of the person in front of them. This is what happens in wartime.

French Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas came out of World War II with a new understanding about the face of the other. Seeing another’s face is the sixth commandment, “Do not murder,” he taught. Once you see the other, you step out of yourself and your natural selfishness and find care for another. It is, in effect, the opposite of the dehumanization that war causes.

Our Kumah Festival this year is a search for the ultimate antidote to killing, the human face, in the midst of war. Each of the four events of the festival will offer a different search for the human face, through the overlapping of art, faith and politics.

Possibly the most amazing face-seeking these days is being done by Combatants for Peace and the Bereaved Parents Circle, when every year on Israeli Memorial Day they produce the Joint Israeli-Palestinian Memorial Ceremony. This unique event has grown to become the largest peace gathering in the world, drawing hundreds of thousands of viewers to witness Palestinians and Israelis mourn together their dead, sing and search for hope. This will be the first year that the event on May 12th will include a New York component, in which I will join with other rabbis and artists to frame the ceremony. Once you have heard a Palestinian speak tenderly about their lost loved one it becomes impossible to categorize all Palestinians as a faceless group.

We tend to think of our history as though it taught us only to distrust and fear others, but that is far from the case. Between the struggles there were long periods of friendship and comraderie with other religious groups. One such moment came in the late fifteenth century. We were kicked out of Spain by the Christians, and many Jews made their way into Muslim controlled lands. A significant contingent of Spanish Jews landed in Turkey and were welcomed by the local community. The people we are conditioned today to see as potential enemies were then the face of our new home. On May 10th, East of the River Ensemble will perform for us songs from that time in our history, when those Spanish Jews learnt Ottoman melodies and created a new form of Jewish music.

The play Here There Are Blueberries, which we will watch on May 16, takes the challenge of the face to the extreme: can we see the face of our murderers, and what does that do to us? This important piece by Tectonic Theatre Company follows the brave work of Holocaust Museum researchers who found photos of Nazi officers on break from Auschwitz. After the performance we will speak with Amanda Gronich, co-writer of the lauded play, and Jonathan Raviv, one of the leading actors. Together we will explore both the gravitational force of the enemy’s face, and the danger that comes with succumbing to its charms.

I hope that when we arrive at our closing event on May 18, which leads us back to the forest in second century Palestine to join the ten mystics, we will be equipped to see not only the face of our enemy but even the face of the divine. With text from the Zohar made into art by the talented artists from Laba, that task should become approachable.

את פניך יהיה אבקש

Sang the psalmist, “it’s your face, YHVH that I seek.” Where else might we seek the face of god other than in the faces of our fellow human beings?

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha