Sort by Category

The Value of Surrender

by Rabbi Misha

In the upside down ways of the world, people want to win. “Total victory,” says one leader, "I didn’t lose, I won big,” says another.

Dear friends,

In the upside down ways of the world, people want to win. “Total victory,” says one leader, "I didn’t lose, I won big,” says another. These are reflections of us and our battles with reality. An attitude that might be more attuned to the deeper truth of our existence is that the desire to win is a mis-formulation of the mind. Instead, we might consider the value of surrender.

“The Gate of Surrender” is the title of the sixth chapter of Rabbi Bahyeh Ibn Pekuda’s eleventh century masterpiece, Duties of the Heart. Reading it is a balm to the ridiculous vanity of our times.

Pekuda describes a person who acts with the value of surrender: “a soft tongue, a low voice, humility at a time of anger, not exacting revenge when one has the power to do so.”

How different would our world be if we all acted with humility at times of anger? How different would our family lives be, our friendships, our relationships with our national and personal neighbors?

Today, one of the worst sources of pride-infused certainty is religion. I guess things weren’t so different a thousand years ago, since the God-touting person’s destructive pride is what led Pakuda to write this chapter:

“...arrogance in the acts devoted to G-d was found to seize the person more swiftly than any other potential damager. Its damage to these acts is so great that I deemed it pressing to discuss that which will distance arrogance from man, namely, surrender.”

Of course, people spouting their righteous anger are not exclusively religious. As a matter of fact, when secular people speak passionately about the horrors they see in the world, and about the justice they fight for, they most often do it with the same religious fervor that people of faith do. Almost everyone these days seems to need to work hard against arrogance:

“...to distance a person from the grandiose, from presumption, pride, haughtiness, thinking highly of oneself, desire for dominion over others, lust to control everything, coveting what is above one, and similar outgrowths of arrogance.”

Surrendering to the deeper reality of our humanness helps.

“One of the wise men would say on this matter: "I am amazed at how one who has passed through the pathway of urine and blood two times (once as semen, the other as a newborn) can be proud and haughty?"

We could continue fighting death for as long as we want. We won’t win. We could continue fighting what is for as long as we want. We won’t win. Accepting this can make the work of improving the lives we live and the world we live in not only more pleasant, but also more effective.

“...for one whom arrogance and pride have entered in him, the entire world and everything in it is not enough for his needs due to his inflated heart and due to his looking down with contempt on the portion allotted to him. But if he is humble, he does not consider himself as having any special merit, and so whatever he attains of the world's goods, he is satisfied with it for his sustenance and other needs. This will bring him peace of mind and minimize his anxiety. But for the arrogant - the entire world will not satisfy his lacking, due to the pride of his heart and arrogance, as the wise man said (Proverbs 13): "A righteous man eats and is full, but the stomach of the wicked never feels full."

צַדִּיק אֹכֵל לְשֹׂבַע נַפְשׁוֹ וּבֶטֶן רְשָׁעִים תֶּחְסָר.

If anything will lead us to victory it is surrender. I pray for acceptance, for gentleness, for the ability to move forward toward goodness with simplicity and truth.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Clear and Present Danger

by Rabbi Misha

Please forgive me in advance for stepping out this week of my rabbinic frame of mind and inhabiting my position as a concerned Israeli living in the US. I won’t be invoking the tradition today, which means I won’t be talking about morality, humanity, responsibility and love.

Israeli-Palestinian peace conference in the Menora Arena calling for an end to the war and a solution to the conflict, Tel Aviv, July 1, 2024. (Photo, Oren Ziv)

Dear friends,

Please forgive me in advance for stepping out this week of my rabbinic frame of mind and inhabiting my position as a concerned Israeli living in the US. I won’t be invoking the tradition today, which means I won’t be talking about morality, humanity, responsibility and love. I won’t be writing about the horrific realities of this war on Palestinians, which we all need to name and face. I won’t be talking about Hamas. I won’t be writing about America. Today, I will simply be writing about the Jews of Israel and the very real danger they are in.

“Hamas’ new response to the offer of the mediators in the negotiations sparked deep disagreements between the PM, Benjamin Netanyahu and all the heads of the security forces.” This line, published yesterday by Amos Harel, one of Israel’s leading military analysts, captures much about the current state of affairs in Israel. Netanyahu is one of the few people still in favor of continuing the war. He seems to be working to scuttle the agreement to release the hostages, while all of the leaders of security forces want this deal. All of them. These are not soft people. They are not dreamers. They are hardened generals and heads of intelligence operations who are meant to protect the country. This is because they see a real and immediate danger to the country if this war continues.

Alarm bells have been ringing for many months. More and more voices in Israel have been calling for de-escalation. Op-eds came out in the last month by two former Israeli Prime Ministers with titles like “We Are in a True Emergency Situation. We Must Lay Siege to the Knesset and Bring Down this Government.” This from a former Ehud Barak, the former IDF Chief of Staff, Minister of Defense and Prime Minister. Ehud Olmert, another former Prime Minister, who spent most of his career in Netanyahu’s Likud party, recently wrote: “Netanyahu wants Israel’s destruction. No Less.”

What is that clear and present danger? There are many dangers, but the leading one is a second war in Lebanon. Yesterday, over 2000 rockets were fired at Israel from Hizballah. 2000 rockets! If they start using their longer-range missiles, they could destroy Tel Aviv. Hizballah is likely to use those missiles if and when Israel launches a ground offensive. Netanyahu seems intent on doing that despite clear signs from Hizballah that it will stop attacking if a truce is reached in Gaza.

This week I heard Amira Hass speak. Amira has been writing for Haaretz for decades and is a unique voice among Israeli and Palestinian journalists. The daughter of two Holocaust survivors, she lived in Gaza for several years, and today she lives in Ramallah. She knows the Palestinian viewpoint from the inside, as well as the Israeli one. Her message this week: You should be deeply concerned about the possibility of huge numbers of Jews being killed in Israel, that will make October 7th seem minor, because the leaders of the Jewish community of Israel are creating conditions that can easily lead to another catastrophe. To prevent this, we need to apply very real pressure on Israel’s government to make a deal and end this war.

I don’t know who still supports this war. It has brought back seven hostages (all the others came back through a negotiated deal) and killed dozens of them, if not more.

In the first four days of July, it has claimed the lives of the following Israeli soldiers:

20 year old Eyal Mimran, killed in Sheja’iya

21 year old Roy Miller, killed in Northern Gaza.

21 year old Elay Elisha Lugassi, killed in Northern Gaza.

38 year old Itai Galea, killed in the Golan Heights.

19 year old Alexander Yekiminsky, killed in a stabbing in the Galilean city of Karmiel.

25 year old Eyal Avniyon, killed in Central Gaza.

30 year old Nadav Elchanan Noler, killed in Central Gaza.

22 year old Yehudah Getto, killed in Tul Karem in the West Bank.

21 year old Uri Yitzhak Hadad, killed in Southern Gaza.

These are Netanyahu’s dead. Yehi Zichram Baruch.

And if you’re asking yourself, what does Misha want from me? What can I do over here? First and foremost, tell your representatives that Netanyahu’s visit to congress is an abomination. Next, remove your support from any organization that blindly supports the Israeli government. I believe these organizations put Israelis in grave danger. Instead, support one of the dozens of organizations that miraculously managed to bring about the largest gathering in Israel for peace in decades, like NIF or Standing Together. My friends and family back home suffer from a far deeper despair and agony than us here. And yet, despite unreal police violence, threats from fanatics, mockery by much of the country and a history of physical assault and even murder of anti-war activists, they continue to go out into the streets to demand change. A rising up is taking place there. Let’s take our cue from the six thousand pro-peace Israelis who came together in Tel Aviv to say End This War.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

But who told me to try to understand?

by Rabbi Misha

In honor of the arrival of summer, two Iberian poems to drive us out of the never-fading anxiousness about the state of the world and into the plain reality of this beautiful season:

Kaitz Niggun (Summer Melody) by Yonatan Gutfeld

Dear friends,

In honor of the arrival of summer, two Iberian poems to drive us out of the never-fading anxiousness about the state of the world and into the plain reality of this beautiful season:

From The Keeper of Sheep by Alberto Caiera (One of the pseudonyms of Portuguase poet Fernando Pesoa)

XXII

As when a man opens his front door on a summer day

And gazes with full face upon the heat of the fields,

Sometimes Nature suddenly hits me smack

In the face of my five senses,

And I get confused, mixed up, trying to understand

I don't know quite what, or how.....

But who told me to try to understand?

Who said there's something to be understood?

When summer passes the soft warm hand

Of its breeze across my face,

I need only feel the pleasure of it being a breeze

Or feel the displeasure because it's warm,

And however I may feel it,

Because that's how I feel it, is what it means to feels it.

The Silence, by Federico Garcia Lorca

Listen, my son: the silence.

It's a rolling silence,

a silence

where valleys and echoes slip,

and it bends foreheads

down towards the ground.

(or in the original Spanish)

El Silencio

Oye, hijo mio, el silencio.

Es un silencio ondulado.

un silencio,

donde resbalan valles y ecos

y que inclina las frentes

hacia el suelo.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

We Must Imagine Job Happy

by Rabbi Misha

As somehow always happens when you study the Book of Job, we ended up chewing on Job’s final words. We were already in hour three or four of our wonderful Tikkun Leil Shavuot this week, which focused on Job, when the words were spoken:

Sam's Point, Minnewaska State Park

Dear friends,

As somehow always happens when you study the Book of Job, we ended up chewing on Job’s final words. We were already in hour three or four of our wonderful Tikkun Leil Shavuot this week, which focused on Job, when the words were spoken:

"לְשֵׁמַע אֹזֶן שְׁמַעְתִּיךָ, וְעַתָּה - עֵינִי רָאָתְךָ, עַל כֵּן אֶמְאַס וְנִחַמְתִּי עַל עָפָר וָאֵפֶר"

Job has lost everything he had, sat silently in his devastation for a week, offered lament after lament. He has heard four of his friends try and talk some good religious sense into him, and then heard God’s voice unleash sweet poetry, that reminds Job of the exquisite beauty of the world. And then we reach this line. I’ve read it hundreds of times in Hebrew, read many different translations of it, translated in myself a few times, heard other translations, argued over it, studied it - but its meaning remains elusive.

The first half of the verse is easier - “I had heard about you with my ears; but now my eyes have seen you.” Stephen Mitchell’s translation stays true to the Hebrew in this case. And all the translators and commentators agree that Job is saying something like that. It’s the second half of the verse that’s harder to grasp. Even when you go word by word and understand each piece of the sentence, somehow by the time you’ve reached the end of it you still aren’t sure what he’s saying.

על כן means “therefore.”

אמאס means something like “I’m sick of it” in modern Hebrew, or “I’ve grown to detest” in some biblical passages, a type of abandoning of an idea or a person or God in others. It is the hardest word to translate in the sentence.

וְנִחַמְתִּי means “I am comforted.”

ּ עַל עָפָר וָאֵפֶר means “over dust and ashes.”

All together it would be something like: “therefore I’m sick of it, and I am comforted over dust and ashes.” Which doesn’t make much sense. Mitchell offers: “Therefore I will be quiet, comforted that I am dust.” Raymond Scheindlin suggests: “I retract. I even take comfort for dust and ashes.” As you see, that word אמאס can really be interpreted very differently. Edward Greenstein translates the first half of the sentence “that is why I’m fed up.” King James goes: “Wherefore I abhor myself.”

My rabbi, Jim Ponet used to make a classic rabbinical exegetical move and say that the written word אמאס should actually be understood like another Hebrew word that sounds almost identical, אמס, which means “I melt.” The suggestion is that Job’s final words are a total softening, a renunciation of anything and everything he previously believed and argued, a type of acknowledgement of the emptiness, in the Buddhist vein. His acceptance of what has happened to him comes in the form of losing his mind’s previous form. But in recent years Rabbi Jim’s seemed to have moved on from that understanding.

It was his son, David who in our Tikkun opened up a new vista on the verse for me. David, the School for Creative Judaism’s Philosopher in Residence, brought in some text from Camus’ The Myth of Sisyphus. Sisyphus is another mythological Job-like character, punished pretty severely: he has to push that huge rock up the mountain over and over again for eternity, watch it roll down and start again. Camus opens his book by asking all of us Sisyphi: how come we don’t kill ourselves, much like Job’s wife asks him in the second chapter of Job. But by the end of his book, he’s managed to embrace the absurdity of the human situation and even find freedom in it. Sisyphus pushes that rock up the mountain. It falls down to the bottom. Sisyphus turns to walk down the mountain again.

“It is during that return, that pause, that Sisyphus interests me,” Camus writes. “That hour, like a breathing space that returns as surely as his suffering, that is the hour of consciousness.” He imagines him walking down the hill. “If the descent is sometimes performed in sorrow, it can also take place in joy.” In other words, while Sisyphus walks down the mountain to begin pushing that huge rock up again, he might be HAPPY. Is he overstating it? “This word is not too much,” he tells us.

Camus’ final lines are some of his most famous, and probably his most ecstatic:

“This universe henceforth without a master seems to him neither sterile nor futile. Each atom of that stone, each mineral flake of that night-filled mountain, in itself, forms a world. The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man's heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy."

And so I ask myself – might one imagine Job happy as well?

I don’t think that’s possible for most of the book. Even Sisyphus' imagined happiness is focused more on the empty pause when he's walking down the hill than on the painful pushing of the rock uphill. Job's arguments with his friends and God are the equivalent of pushing the rock up the mountain. The question is whether at the end, in the 42nd chapter, when he speaks his last lines, we can imagine him happy. Remember, this is before God announces that he was right all along, and before he gets everything he had at the beginning back twofold. For Job “the hour of consciousness” must be that moment during which says:

“I had heard about you with my ears; but now my eyes have seen you."

We must imagine Job happy when he says these words. His “comfort over dust and ashes” must be a warm and beautiful sentiment. He has made peace with death, and in so doing he has made peace with life. That elusive word, אמאס, must be part of that process of finding joy. At the Tikkun I thought maybe it means: “I give up. I raise the white flag. I surrender. No more war. No more fighting. No more demanding that reality conform to my needs. I am now ready to experience comfort, to sit in what is.”

So for today, this Shabbat, I raise the white flag. I give up on trying to understand the best translation of this verse. I give up on understanding, on insisting that this world be different than it is. Instead, I imagine myself happy, surrounded by the sweet-scented summer air, resting in the gift of Shabbat.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

The Cuckoo's Punishment

by Rabbi Misha

Amazingly in synch with the times, this Shabbat’s parashah deals with reward and punishment.

Dear friends,

Amazingly in synch with the times, this Shabbat’s parashah deals with reward and punishment. Sixteenth century Rabbi Yaakov Ben Yitzhak Ashkenazi writes:

The Holy One said: I have said that I properly pay each one according to their deeds, so how is it that an evildoer is very rich? Concerning this, the Holy One responds that the wealth of the evildoer, when he gathers wealth through theft or usury, it does not remain long. A bird called a partridge, sits on the eggs of other birds and incubates them. When the birds hatch from these eggs, they do not follow this bird, but they leave and follow their own. So too is the wealth of the evildoer. Similarly, when he has lots of money it will not remain with him for long. The wealth must depart during his lifetime and in the end he will be left a wretch.

The rabbi was working on the following verse in this week’s Haftarah:

קֹרֵ֤א דָגַר֙ וְלֹ֣א יָלָ֔ד עֹ֥שֶׂה עֹ֖שֶׁר וְלֹ֣א בְמִשְׁפָּ֑ט בַּחֲצִ֤י יָמָו֙ יַעַזְבֶ֔נּוּ וּבְאַחֲרִית֖וֹ יִהְיֶ֥ה נָבָֽל׃

Like a partridge hatching what she did not lay

So are those who amass wealth by unjust means;

In mid-life it will leave them,

And in the end they will be proved fools.

In the 11th century, Rashi explained this bird bahavior a little bit differently:

This cuckoo draws after it chicks that it did not lay. דָגָר (the second word in the verse)- This is the chirping which the bird chirps with its voice to draw the chicks after it, but those whom the cuckoo called will not follow it when they grow up for they are not of its kind. So is one who gathers riches but not by right.

Steinsaltz, in the 20th century offered yet a different bird bahavior:

A partridge, a small wild bird from the pheasant family, collects and tries to incubate eggs that it did not lay. When several of these birds share a nest, there is often a struggle between them, with each trying to expel the others and gather all of their eggs under its own wings. Since the partridge’s wings are fairly short, it cannot protect and properly incubate the stolen eggs, many of which are ultimately ruined or abandoned. This is a metaphor for a dishonest person, one who amasses wealth unjustly. Just as the partridge does not benefit from the eggs it stole from others, so too such an individual will not profit from his wealth. In the middle of his days he will leave it, and at his end he will be reviled, disgraced, and wretched, or, alternatively, he will be revealed and recognized as a wicked criminal.

19th century Malbim had a different view, not of the bird's bahavior but of the thief’s punishment. While he may lose his money, he’ll never lose the terrible nature he adopted.

באחרית ימיו יהיה עוד גרוע ממי שלא היה לו עושר כלל, שהגם שלא היה עשיר מימיו לא היה נבל אבל הוא ישאר נבל, כי ישאר בו הטבע לעשוק ולחמוס ולעשות נבלה

In his old age he will be worse off than one who never had any wealth, since the one who was never rich was also never a scoundrel – but he will stay a scoundrel, because the instinct to oppress, be violent and spread corruption will never leave him.

No matter how exactly this bird metaphor is supposed to work, and what a partridge actually does with the eggs or the chicks that it steals, eventually, says the prophet, truth will manifest, and even the king’s nakedness will be revealed.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Truly Letting Go

by Rabbi Misha

An interview with Authentic Movement teacher, Eileen Shulman

Mystical artwork by Danielle Alhassid, piano Damian Olsen

Dear friends,

An interview with Authentic Movement teacher, Eileen Shulman

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Time to Break it

by Rabbi Misha

There come times when the only thing to do is to break the rules; to go against the foundational principles; to do the exact opposite of what you always believed to be right. Is this one of those times?

Mystical artwork by Danielle Alhassid, piano Damian Olsen

Dear friends,

There come times when the only thing to do is to break the rules; to go against the foundational principles; to do the exact opposite of what you always believed to be right. Is this one of those times? The world seems in bad enough shape to warrant a shakeup. Tomorrow night we will harken back almost two thousand years to a time when the human situation was so bad that ten mystics decided that the only way to heal was to break the most foundational laws, the pillars on which our entire faith stands.

עת לעשות ליהוה הפרו תורתך, they declared,

It is time to do for God – so break the Torah!

This is the first verse quoted by Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai in what is called the Great Gathering, or the Idra Raba, a wildly poetic segment of the Zohar which we will delve into tomorrow. It describes a nighttime rabbinical retreat to the forest designed to alter the spiritual position of the divine realm, during a time of continuous wars and real threat to the continued survival of Judaism.

Bar Yochai’s reading of the verse is, of course, subversive. The line from Psalms is usually understood differently: “It is time do for God – for they have broken your Torah!” But Bar Yochai builds on the earlier subversive sages of the Talmud who suggested switching one vowel in the sentence to another to twist scripture into a new meaning. HEferu becomes HAferu, and thus turns the verb “to break or undo” from third person plural past tense (they have broken) to second person plural imperative (Break!).

This begins the process of taking the worst offense in our faith – giving form to the formless abstraction we call God – and turning that offense into a divine commandment. In this transgressive story, the rabbis understand that the way to realign the divine world, which will then flow into humanity, is to paint into existence the face of God. Their method is poetic exegesis: they take biblical verses to create an image of God’s face: skull, brain, eyes, nose, ears, beard. Then they chart how each facial element relates to the millions of worlds and planets and realities of our world.

While they’re at it, they decide to break down the next holy cow, the notion of one God. Once the God of Compassion is established, they paint the face of a second God – the God of Judgement. And once he is completed, they paint the Goddess. Finally, they unite the three through the poetry of love, and bring harmony back into the universe.

There are countless levels on which we stand to learn from this psychedelic mystical recounting. The act of intervening in the flow of the universe denotes a belief in human power that we have lost. The method of intervening, which combines faith, art and knowledge with a political intention is very different to the ways we have been fumbling about trying to change things. The courage to smash our holy structures in order to allow for a new flow is key to the release that a new reality would demand.

The Zohar is notoriously difficult to grasp. It needs to be invited into your senses. So the pieces of text we chose for our final Kumah event tomorrow night will both be explained by Rabbi Abby and me during the event, and, more importantly, accompanied by music and art. We will be joined by pianist Damian Olsen, performance artist Danielle Alhassid and vocalist Chanan Ben Simon. Much like the Idra Raba itself, we will proceed through structured improvisation to produce the beauty and wonder which we hope will afford a smooth internal and external flow between us and the source of all.

Join us tomorrow night at the 14th Street Y to break down the structures of reality and use the shards of that reality to paint a new world into existence.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Rise Up and Hope

by Rabbi Misha

War engenders despair. It gets in your head and speaks about your meaninglessness and powerlessness. It kills people as a means of killing hope. Which never works. Like life, hope continues.

Our hosts Steff and Ronnie at the Gotham Depot Moto, where we open the Kumah Festival this evening.

Dear friends,

War engenders despair. It gets in your head and speaks about your meaninglessness and powerlessness. It kills people as a means of killing hope. Which never works. Like life, hope continues.

Our Kumah Festival this year, which begins tonight, is a path to hope, a reminder of our ability to rise above the noise and rise up over obstacles of displacement, oppression, hatred and loss.

We begin this evening with the devotional music of the Jews of Turkey, who found refuge from the blood-thirsty Catholics of Spain not only in the lands of the Ottoman Empire, but also in its music. They countered despair with delight, death with poetry, wickedness with neighborly love. We will attempt the same with the music of East of the River, the food of Chef Sami Katz and the incredible motorcycle-filled space at Gotham Moto Depot.

Then on Sunday we will come back to the present with the Joint Israeli-Palestinian Memorial Ceremony. This is a sad gathering, there’s no doubt. But the beauty that comes every year out of the honest sharing of grief of those who are meant to be enemies is an antidote to any of the words of the sad excuse for politicians that we are used to hearing on these topics. Sharing sorrow, bringing hope, as the Bereaved Parents Circle, one of the leading organizations calls it.

The final two events on Thursday and next Saturday will approach the question of hope through two of the ancient ways human beings have used to stay focused on the right and the good: theater and mysticism. I am sure that this series of events will give us a lot of perspective, strength and energy to dive back into the burning task of ending this war and preventing the next.

See you tonight among the motorcycles!

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Real Peace

by Rabbi Misha

When the Holy Blessed One came to create Adam the first human, the ministering angels divided into various factions.

Daphna Mor and the musicians of East of the River will open our Kumah Festival on May 10th.

Dear friends,

When the Holy Blessed One came to create Adam the first human, the ministering angels divided into various factions. Some of them were saying: ‘Let him not be created,’ and some of them were saying: ‘Let him be created.’ This is what is referenced in the Psalms when it is written: “Kindness and truth met; righteousness and peace touched” (Psalms 85:11). Kindness said: ‘Let him be created, as he performs acts of kindness.’ Truth said: ‘Let him not be created, as he is all full of lies.’ Righteousness said: ‘Let him be created, as he performs acts of righteousness.’ Peace said: ‘Let him not be created, as he is all full of discord.’ What did the Holy Blessed One do? He took Truth and cast it down to earth, as is written: “You cast truth down to the earth.” (Daniel 8:12). The ministering angels said before the Holy Blessed One: ‘Master of the universe, what are you doing?! Let Truth rise up from the earth!’ As is written: “Truth will spring from the earth” (Psalms 85:12).

While the ministering angels were busy arguing with one another the Holy blessed One created Adam. He said to them: ‘Why are you deliberating? Adam has already been created.’

So much of the essence of the events of the last week are captured in this ancient midrash. Like the angels, we are passionately arguing over humanity, over Israel, while reality keeps flowing. From our American island we yell and scream, while in Gaza the madness is not theoretical. Hirsh cries out to us waving his mutilated arm. The Israeli Minister of Finance demands “total annihilation,” while the tanks line up on the border, and the two men leading this rabid tango continue to display their sick selfishness.

Last week I had a moment of pride, when Rabbi Abby joined other Jews, American and Israeli to try to deliver food to Gaza. They were stopped a couple kilometers from the border crossing, but for a moment the hollow words from the Seder: “Let all who are hungry come and eat,” were given some depth when Abby and the other Rabbis for Ceasefire spoke about the hunger across that border.

The truth is I’m hungry. Hungry for quiet, for humility, for a world that doesn’t constantly provoke the earth to spew us out. Nachmanides said that the difference between the land of Israel and anywhere else is that unlike other places, Israel vomits away the people who defile it through moral abominations. I’m not sure that’s only true of Israel.

Monday is Holocaust Remembrance Day, the day on which we recall when the Jews paid the price for the moral abomination called Europe. We are still recovering from that. Even 79 years after that war ended there are still close to one million less Jews in the world than there were in 1939. Each antisemitic chant pushes us further away from recovery. And each Palestinian child who dies too.

This week’s Haftarah is one of the clearest ethical rebukes of a nation, in a bible full of them. Speaking to Jerusalem, “the city of blood,” the prophet Ezekiel enumerates the moral, social and religious abominations of the Jews of the city – which he already knows will lead to the land spewing them out.

הִנֵּה֙ נְשִׂיאֵ֣י יִשְׂרָאֵ֔ל אִ֥ישׁ לִזְרֹע֖וֹ הָ֣יוּ בָ֑ךְ לְמַ֖עַן שְׁפׇךְ־דָּֽם׃

Every one of the leaders of Israel in your midst uses their strength for the shedding of blood.

The punishment is coming, says the prophet, the circle is coming around, and he urges the people to consider their frailty:

הֲיַעֲמֹ֤ד לִבֵּךְ֙ אִם־תֶּחֱזַ֣קְנָה יָדַ֔יִךְ לַיָּמִ֕ים אֲשֶׁ֥ר אֲנִ֖י עֹשֶׂ֣ה אוֹתָ֑ךְ אֲנִ֥י יְהֹוָ֖ה דִּבַּ֥רְתִּי וְעָשִֽׂיתִי׃

Will your heart be able to stand it? Will your hands still hold any strength in the days when I deal with you? Unlike you, I, YHVH, am not all talk.

Our fate, suggests the prophet is not sealed. Goodness could appear in a flash; as quick as regret, as sudden as a realization; “a flash of lightning,” as Nietzsche put it:

"Rendering oneself unarmed when one had been the best armed, out of a height of feeling – that is the means to real peace, which must always rest on a peace of mind; whereas the so-called armed peace, as it now exists in all countries, is the absence of peace of mind."

When our ancestors were kicked out of Spain they found refuge in Turkey. While their leaders debated how to stay alive - like the angels in the Midrash - the musicians offered peace of mind through the new music they encountered there. They were alive, they were singing, they were at peace. As we prepare to open our Kumah Festival next Friday with that very music, let the memory of the six million remind us who we are: a nation of wandering improvisors, whose weapon and saving grace has always been our imaginative mind. May we return to it and find a real peace.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Festival of Faces

by Rabbi Misha

In the second century in Palestine, after the failed Bar Kochva rebellion, the Roman Emperor Adrianus imposed harsh laws on the Jews that included forbidding the practice of the religion.

Dear friends,

In the second century in Palestine, after the failed Bar Kochva rebellion, the Roman Emperor Adrianus imposed harsh laws on the Jews that included forbidding the practice of the religion. Many Jews were killed in the decades leading up to these decrees and many more will perish. in the midst of the struggle, 10 rabbis left their dwelling in the Galilee and went into the forest at night. They needed to shift the spiritual gravity center of the world, which was off in dangerous ways. They saw how people were not seeing one other. They would look one another in the face and see nothing. The problem, the rabbis understood, stemmed from the same thing happening in the divine world. The two faces of the divine, the male and the female, the God and the goddess turned away from each other. If they could turn them to face one another, the realignment in our world would be felt, and people would once again be able to see one another’s faces.

Our world today seems to be suffering from a similar problem. Too many people are caught in frameworks of thinking that prevent them from seeing the simple humanity of the person in front of them. This is what happens in wartime.

French Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas came out of World War II with a new understanding about the face of the other. Seeing another’s face is the sixth commandment, “Do not murder,” he taught. Once you see the other, you step out of yourself and your natural selfishness and find care for another. It is, in effect, the opposite of the dehumanization that war causes.

Our Kumah Festival this year is a search for the ultimate antidote to killing, the human face, in the midst of war. Each of the four events of the festival will offer a different search for the human face, through the overlapping of art, faith and politics.

Possibly the most amazing face-seeking these days is being done by Combatants for Peace and the Bereaved Parents Circle, when every year on Israeli Memorial Day they produce the Joint Israeli-Palestinian Memorial Ceremony. This unique event has grown to become the largest peace gathering in the world, drawing hundreds of thousands of viewers to witness Palestinians and Israelis mourn together their dead, sing and search for hope. This will be the first year that the event on May 12th will include a New York component, in which I will join with other rabbis and artists to frame the ceremony. Once you have heard a Palestinian speak tenderly about their lost loved one it becomes impossible to categorize all Palestinians as a faceless group.

We tend to think of our history as though it taught us only to distrust and fear others, but that is far from the case. Between the struggles there were long periods of friendship and comraderie with other religious groups. One such moment came in the late fifteenth century. We were kicked out of Spain by the Christians, and many Jews made their way into Muslim controlled lands. A significant contingent of Spanish Jews landed in Turkey and were welcomed by the local community. The people we are conditioned today to see as potential enemies were then the face of our new home. On May 10th, East of the River Ensemble will perform for us songs from that time in our history, when those Spanish Jews learnt Ottoman melodies and created a new form of Jewish music.

The play Here There Are Blueberries, which we will watch on May 16, takes the challenge of the face to the extreme: can we see the face of our murderers, and what does that do to us? This important piece by Tectonic Theatre Company follows the brave work of Holocaust Museum researchers who found photos of Nazi officers on break from Auschwitz. After the performance we will speak with Amanda Gronich, co-writer of the lauded play, and Jonathan Raviv, one of the leading actors. Together we will explore both the gravitational force of the enemy’s face, and the danger that comes with succumbing to its charms.

I hope that when we arrive at our closing event on May 18, which leads us back to the forest in second century Palestine to join the ten mystics, we will be equipped to see not only the face of our enemy but even the face of the divine. With text from the Zohar made into art by the talented artists from Laba, that task should become approachable.

את פניך יהיה אבקש

Sang the psalmist, “it’s your face, YHVH that I seek.” Where else might we seek the face of god other than in the faces of our fellow human beings?

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

How to Do Passover This Year

by Rabbi Misha

Wishing you a happy Passover, a Zissen Pesach and Shabbat shalom.

Pre Passover Seder this week at our Hebrew School branch in Windsor Terrace

Dear friends,

Last Friday at Kabbalat Shabbat I chose to speak about how to prepare ourselves for Passover this year. Although in the background of what I said was the relationship between Jewish liberation and Palestinian oppression, I purposefully avoided speaking about the war head on, for the first time since October 7th. When the service ended Maia thanked me for my words but expressed dismay at the fact that I hadn’t named the difficulty this year. How could we celebrate freedom while we are killing tens of thousands and displacing millions? Everyone I know who will be at a seder this year is asking themselves a variation of that question. So instead of schmoozing, I suggested we sit down with whoever would like, to discuss it.

Of the many honest, thoughtful voices, it was Rene’s that stayed with me most. “In the camps,” she said, recalling her childhood escaping the Nazis, “people celebrated Passover. There was hunger – just like the hunger in Gaza today – so people took the horse feed, ground it into flour and baked Matzah out of it.” This short description cut to the chase of it all. Anyone there who thought that it’s impossible to celebrate Passover this year, immediately questioned their attitude. And anyone who thought they could ignore the war at their Seder this year couldn’t shake the Holocaust survivor’s clear-eyed comparison of the human situation in the camps and Rafah.

So how do we do it?

Ezzy was sick this week, which gave me a chance to read some of the Haggadah with him.

בכל דור ודור חייב אדם לראות עצמו כאילו הוא יצא ממצרים, he read.

“In each generation each person must see themselves as if they came out of Egypt.”

“Why,” he asked.

“What do you think it does, to imagine that you came out of Egypt?”

“Makes you appreciate what you have,” says Ezzy.

“Is that it?”

“It also makes you relate to other people’s suffering.”

I find these two pieces the keys to this year’s holiday. We can’t ignore the first one: the family and friends gathering, the joy of being together, the beauty of our traditions. Nor can we unhear the cries we have heard, the images we have seen, the situation our Palestinian brothers and sisters are in, and the one our Israeli brothers and sisters are in.

There’s one thing missing in this picture though, and that’s the way Passover connects us to the miraculous. Last Saturday’s thwarted Iranian attack was not quite the parting of the sea, but it was still miraculous. When we open the door for Elijah, let it help us keep the door open to the possibility of unexpected change. Let us remember that peace can come, that despair can be overcome, that human wickedness, greed and stupidity, has – incredibly - not completely undone us up to this point in history, and may yet be transformed.

This week’s Haftarah describes the type of reconciliation that Elijah’s return brings:

וְהֵשִׁ֤יב לֵב־אָבוֹת֙ עַל־בָּנִ֔ים וְלֵ֥ב בָּנִ֖ים עַל־אֲבוֹתָ֑ם

And the hearts of parents will turn back toward their children,

and the hearts of children toward their parents.

I leave you with one suggestion for a transformation of the text of one sction of the Haggadah that seems appropriate this year. Written by Elana Blum from the NYC Anti-Occupation Block, it suggests that something’s got to be different about this year’s Seder, maybe even radically so, but we have to build it on the Seder as we know it. Instead of the usual text about the four children, and how parents should deal with each type, we find the opposite. Maybe instead of parents teaching kids, this is the year that parents learn from their kids.

“The Four Parents”

by Elana Blum

With love to your people and mine / Passover 5784 (2024)

1. The wise parent says, ‘Here are all the laws which God commanded us to observe on Passover, and all the customs of the Seder. Come and study them with me.’ To this parent you shall say, ‘I will study our laws and customs with you, and I will also think about them in new ways.’ And you shall share your thoughts with them, even those they do not recognize, so they can see that you will treasure the legacy and make it yours.

2. The wicked parent says, ‘How dare you reject my tradition and my version of our history? You do not belong at my table.’ To this parent you shall say, ‘it is because you value me only as a reflection of yourself that I reject your teaching. I will read our story in my own way, and you will not be part of it.’

3. The simple parent says, ‘We are having a feast with matzo tonight! Eat, my child.’ You shall say to them, ‘I do not love matzo. But I learned that we eat it because our ancestors escaped from slavery, and I will tell you the story.’

4. As for the parent who does not know how to teach, you must begin for them, and explain: ‘This ritual belongs to us, and I will bear it forward.’

Wishing you a happy Passover, a Zissen Pesach and Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Point of Departure

by Rabbi Misha

The story of this war begins on October 7th, 2023. No, it begins several years earlier when Gaza was closed off. No, it begins in June 2007 when Hamas beat Fatah and took over the Strip.

Jacob as outer space Haman with the mask he made at Herbrew school

Dear friends,

The story of this war begins on October 7th, 2023. No, it begins several years earlier when Gaza was closed off. No, it begins in June 2007 when Hamas beat Fatah and took over the Strip. No, it begins on August 16th, 2005 when Israel pulled out of the Strip. No, it begins November 5th 1995 when Rabin was assassinated. No, it begins in 1967 when it was conquered. No, in 1948 when hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees arrived. No, in 1939 with Hitler. No, in 1897 in the First Zionist Congress. No, it really begins on October 8th, 2023.

Different ways of telling the story create vastly different stories, with incredibly different messaging, and very different realities. The point of departure is key, in both senses of the word “point.” At which point in time do you begin your telling, and what is the purpose of your story?

This is true for the war, and it is no less true for our national and religious stories.

In the last century BCE, our rabbis of blessed memory were tasked with framing the story of Hanukkah. The tale they had been handed down was one of victorious religious zealot-warriors. The nationalistic story of the Maccabees, the oppressed few who took up arms and beat the great Greek army was accompanied by violent acts of bigotry toward the less nationalistic Jews. The rabbis decided to completely transform the story. Theirs began at the end of the war, when the search for holy oil began at the temple. For hundreds of years the focus of the holiday was the miracle of the oil. It was only after the Holocaust when the Zionist movement brought the Macabbees back into the forefront, as a means of empowering a beaten down nation with the possibility of taking history into their own hands.

For the past three weeks I have been in the business of challenging the way we tell the Passover story. This weekend we are devoting two performances of Pharaoh to a discussion about how we tell our stories. Last night, in the talkback with Rabbis for Ceasefire, we examined the relationship between the way the Exodus story is told, and the story Jews tell about this current war.

Tomorrow night we will be joined by Professor Richard Schechner, a theater visionary who changed the way stories are told in the theater, by bringing a multi-cultural approach to the stage. In my “Intro to Theatre” class in undergrad I was taught about Schechner’s work on Rasa, an ancient Indian approach to emotion in performance, which offers an antithesis to the realistic acting style practiced in the west. The melding of ancient sensibilities with contemporary edge, which Schechner explored with The Performance Group, (later to become The Wooster Group) brought about an entire new field called Performance Studies. Schechner is considered the pioneer and leader of this influential movement.

When we seek other modes of storytelling, even for our own stories, we open ourselves to fresh thinking, and invite not only our familiar methods, but the universal mind that exists within each of us. The prophet Ezekiel promises us in this week’s haftarah that we will be offered “a new heart.” “I will remove from you the heart of stone, and will give in you a heart of flesh,” we are promised. May our stories, and the ways we tell them bring us closer to that reality.

I hope you can snag one of the few remaining tickets and join me tonight or Saturday at 8pm (with Prof. Schechner), or Sunday at 3pm for the final performances of Pharaoh.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Wear Your Enemy

by Rabbi Misha

In 1934, in the dead of winter, the chief rabbi of Palestine, Harav Kook received an urgent telegram. Three Jews escaping persecution were caught making their way through the snow from Russia across the Polish border. Their white clothes used for camouflage didn’t help.

Jacob as outer space Haman with the mask he made at Herbrew school

Dear friends,

In 1934, in the dead of winter, the chief rabbi of Palestine, Harav Kook received an urgent telegram. Three Jews escaping persecution were caught making their way through the snow from Russia across the Polish border. Their white clothes used for camouflage didn’t help. Now they were about to be handed over to the Russian authorities to suffer the penalty by Russian law for such a crime: death. The rabbi sprung into action, sent some urgent communications, and miraculously, managed to release the three and bring them to Palestine. They arrived 90 years ago today, on the eve of Purim, into a drunken celebration. When they recited: “cursed is Haman who tried to annihilate me,” they knew what they were talking about.

In the midst of the rejoicing the chief rabbi, born and raised in the Russian empire, did something unexpected. He began singing an old Russian soldier’s song. He danced and sang, and the entire community joined in on the song.

Now why would the rabbi bring such a strong representation of the enemy that almost killed three innocent Jews? And why would he get everyone present to sing and dance to it? Is this not the moment to celebrate the prisoners’ release, rather than reminding them of the songs of their captors?

The answer is no. It’s exactly the way Purim brings healing. The Holiday of Peace, as Rabbi Natan of Nemirov called it, is exactly the time to step into our enemies’ mindset, to explore our adversaries’ emotional world, to transform ourselves into those we disagree with in an overwhelming show of empathy. We dress in costume to get out of ourselves. We get drunk in order to allow a softening of the hard lines in our thinking. It is the only time of year when we are commanded to see something different in those we hate.

In wicked people there is a spark of goodness. In cruelty there are remnants of kindness. In Haman too there is god.

When we enter this mindset what we find is not agreement with those with whom we disagree, but a softer understanding for a day, a relaxing of the shoulders, a greater harmony in the world.

Many voices have called for a purim with no groggers this year. They see in it a representation of the vengeful mindlessness that is far too present in this war. Perhaps the noisemaking can be transformed as well, from a mocking cry of victory to a call to the spark in the soul of wickedness.

Tomorrow evening we will gather at the theater to watch Pharaoh, drink, munch and make merry. This play is an attempt to help us all wear Pharaoh, in order to increase empathy, soften our hard lines, and open a window to a more harmonious human kind. It has been wonderful witnessing both spectators and critics respond so powerfully to this message. I hope you can join us!

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Attention Is Love

by Rabbi Misha

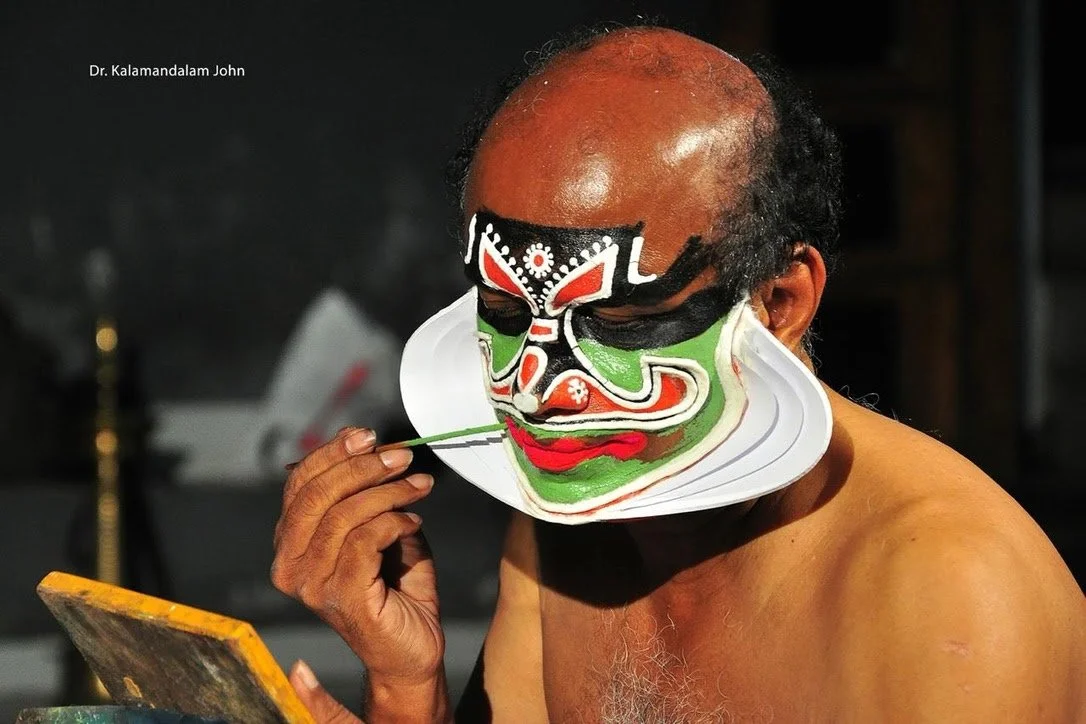

Last night we finally got to see John get made up and assisted into his costume. It’s a process that takes several hours.

Some of Kalamandalam John's Kathakali costume for Pharaoh, laid out in preparation to be worn, including the four-piece-crown.

Dear friends,

Last night we finally got to see John get made up and assisted into his costume. It’s a process that takes several hours. His wife, Marie, a Kathakali make-up artist, carefully applies the special dyes and powders onto his face in precise designs created hundreds of years ago. She paints his face red, green and white, and his forehead black. Then begins the process of putting on the costume. Piece by piece, in a particular order handed down through the generations, the forty pounds of dozens of costume pieces are attached. It begins with the bells on the legs and works its way all the way up to the crown of the head.

Each costume piece is made by a specialized artisan, using specific materials. Tremendous care is placed into every detail. The crown alone takes one month of work by a carpenter, and another month by a decorator. No one may wear shoes around the costumes. These are sacred garments. Without the right attitude, the ritual will not be fulfilled, the magic won’t happen.

Never before have I taken in this week’s parashah so clearly:

וּמִן־הַתְּכֵ֤לֶת וְהָֽאַרְגָּמָן֙ וְתוֹלַ֣עַת הַשָּׁנִ֔י עָשׂ֥וּ בִגְדֵי־שְׂרָ֖ד לְשָׁרֵ֣ת בַּקֹּ֑דֶשׁ וַֽיַּעֲשׂ֞וּ אֶת־בִּגְדֵ֤י הַקֹּ֙דֶשׁ֙ אֲשֶׁ֣ר לְאַהֲרֹ֔ן כַּאֲשֶׁ֛ר צִוָּ֥ה יְהֹוָ֖ה אֶת־מֹשֶֽׁה׃

וַיַּ֖עַשׂ אֶת־הָאֵפֹ֑ד זָהָ֗ב תְּכֵ֧לֶת וְאַרְגָּמָ֛ן וְתוֹלַ֥עַת שָׁנִ֖י וְשֵׁ֥שׁ מׇשְׁזָֽר׃ וַֽיְרַקְּע֞וּ אֶת־פַּחֵ֣י הַזָּהָב֮ וְקִצֵּ֣ץ פְּתִילִם֒ לַעֲשׂ֗וֹת בְּת֤וֹךְ הַתְּכֵ֙לֶת֙ וּבְת֣וֹךְ הָֽאַרְגָּמָ֔ן וּבְת֛וֹךְ תּוֹלַ֥עַת הַשָּׁנִ֖י וּבְת֣וֹךְ הַשֵּׁ֑שׁ מַעֲשֵׂ֖ה חֹשֵֽׁב׃

“Of the blue, purple, and crimson yarns they also made the service vestments for officiating in the sanctuary; they made Aaron’s sacral vestments—as יהוה had commanded Moses. The ephod was made of gold, blue, purple, and crimson yarns, and fine twisted linen. They hammered out sheets of gold and cut threads to be worked into designs among the blue, the purple, and the crimson yarns, and the fine linen.”

This is just a brief segment from the Torah’s careful description of the priest’s clothes, which is imbued with that very sense of specificity and attention to detail that we witness in John’s costume. Theater, we are reminded, is ritual. Religion, we are reminded, is theater.

One of the thin threads connecting the two is the loving attention we pay to performing these rituals as they should be done. Why? For the sake of the ritual.

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve performed plays that I’ve worked on for months in front of a handful of people, for little to no money, without more than a few clapping hands in return. Traditional all night Kathakali performances are usually watched by small audiences, often comprised of Kathakali students. They do it for the sake of doing it. Lishma, as the Jewish tradition calls it, for its own sake. This is the secret. When a human goal is removed from what we do, we can pay very close attention to it, and that in itself is peace. We suddenly find ourselves in love. In other words, attention is love.

If you haven’t noticed yet, I’m eager to share my play, Pharaoh with you all. I hope you can come see it sometime between this evening when we open, with the grace of God, and March 31st when we close. John has invited those who would like to see it, to come watch some of the process of putting on his make-up and costume. Make up will begin around two and a half hours before showtime. Shoot me an email if you plan on coming to see it.

And for those of you staying home tonight, please join the virtual Shabbat that Rabbi Abby will be leading this evening.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Religion in Technicolor

by Rabbi Misha

Every spring, exactly one week before Passover a unique ritual takes place in the South of India. The local Jews leave their towns, cities and villages, and make pilgrimage to a small, holy mountain tucked away to the east of the backwaters.

A different kind of holiday celebration at the School for Creative Judaism

Dear friends,

Every spring, exactly one week before Passover a unique ritual takes place in the South of India. The local Jews leave their towns, cities and villages, and make pilgrimage to a small, holy mountain tucked away to the east of the backwaters. As the sun sets, they climb the 1800 steps that lead up to the mountaintop shrine, where they gather to watch the play that they have seen every year since their birth. It depicts the Pharaoh of Egypt’s struggle to understand how he brought about the death of his first-born son in the tenth plague.

After lighting the ritual flames, they watch him tell the story we all know of the Hebrew slaves’ leader Moses, and the ten plagues he brought upon Egypt in order to secure their release from slavery. They hear Pharaoh’s reasoning for refusing to let the Hebrews go and watch him turn from an all-powerful god-king to a sad, broken father. And then they walk down the mountain singing a psalm of humility.

They have felt the pain of their enemies. They have witnessed the consequences of their fight for freedom. They have internalized their adversary’s perspective. They have shed a layer of certainty and gained a layer of understanding.

Now they are ready to celebrate Passover.

There is no lost Jewish tribe of South India that performs this ritual. I made it up when I sat down this week to write my playwright's note for my play, PHARAOH. But what if there were such a tribe with that ritual? What if this were a tradition right here in New York City, which would take place at the highest point in Fort Tryon Park, or on Mount Prospect Park, or up the river over the Hudson? How would it change our experience of Passover? Our relationship with liberation? What would the inclusion of a ritual play in our religious practices do to our experience of our faith tradition? What would preparing for Passover by diving into the inner world of Pharaoh do to our national psyche and our political behavior in the world?

It has always seemed to me, and I’m oversimplifying here, that Jews have a hard time imagining the Palestinian experience. “There is no Palestinian people,” they would tell me as a kid, even as I would see people hanging up a Palestinian flag on the lamppost beyond the fence of my elementary school in Jerusalem. I was never taught anything about the history and culture of those we shared the land with. They were often represented simply as terrorists. There was an incredible flattening of the humanity and the culture of our neighbors.

The story of the telling of the exodus is not dissimilar. We grow up with a stick figure cruel king who kept saying "No, no, no," for no reason whenever the Hebrew freedom fighter would ask him to let the slaves go. That's not far from how the Haggadah tells it too.

The Torah, however gives a richer depiction of Pharaoh. in several interactions he listens quite carefully to Moses, and makes him offers that seem like they should satisfy his requests. "חטאתי ליהוה," the king even says to Moses a few plagues in, "I have sinned to YHVH." Is that not at least the beginning of a repentance process?

Furthermore, the king of Egypt offers perhaps the thorniest problem regarding free will in the entire Torah. Over and over again we are told that "YHVH hardened Pharaoh's heart." It appears so many times that the commentators have to excuse this breach of human freedom - upon which the entire belief system is founded! - with the excuse that God only hardened Pharaoh's already hard heart. Not only is this a weak excuse, but it also negates a prime principle of rabbinic biblical exegesis, that every word in the Torah is exactly right, and holds both straightforward and deeper meanings. The matter serves to further enrich the king's character, who appears to be moved to denying the Hebrew's demands by God, rather than his own impulse.

The Torah, in other words, offers us a nuanced character, Since then, this biblical character has been systematically flattened into the one that appears in our children's songs, out of a human desire for simplicity. We seem to be wired to need black and white in order to function. But that is precisely what creates a colorless reality.

PHARAOH, which opens a week from today was the play I wrote as my main project toward becoming a rabbi. I wrote it as a rejection of the black and white that led us to October 7th, as well as October 8th through today; a rejection of the knee-jerk vilification of those we disagree with; and an invitation to recreate our ancient faith traditions as complex, forward-looking frames, through which we can see all the colors of the rainbow.

I hope you can join us this evening for a colorful New Shul Shabbat of Peace, which will include an array of incredibly talented Broadway singers and musicians, freedom songs by the inimitable Rob Kaufelt and prayers for a better world.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

One (and only?)

by Rabbi Misha

Before I begin, I'd like to invite you all to a very special gathering we're holding this evening, which can connect us to both the reality of the current situation in Israel/Palestine, and the hopeful ways people are working to overcome it.

Kalamandalam John

Dear friends,

Before I begin, I'd like to invite you all to a very special gathering we're holding this evening, which can connect us to both the reality of the current situation in Israel/Palestine, and the hopeful ways people are working to overcome it. Spirit of the Galilee is an important organization working on co-existence between different faiths and cultural groups in the north of Israel. We will be joined by Ghadir Haney, a renowned and highly influential Muslim social activist, from the city of Acre, Fr. Saba Haj, the leader of a 5,000-member Christian-Arab-Orthodox Church in the town of Iblin, and Rabbi Or Zohar, Reform Rabbi of the Misgav region and director of the Spirit of the Galilee Association (SOG). These are critical voices for us to hear and take in here in the US, and I hope you can all join in person or tune in.

And now I'll pick it up from where I left off last week.

When he was fifteen years old, John was living a perfectly normal life for a Christian teenager in the South Indian state of Kerala. He went to the local school, and to the nearby Orthodox church for religious instruction . And then something happened that radically changed his life. He went to the theater.

Kerala is home to two of the oldest existing theatrical traditions in the world, which are kept as national treasures, but watched by very small audiences. Kudiyatam is the slower and more drama oriented form, in which a play lasts between 9 and 43 nights, each night between 2-5 hours. Kathakali is a form of dance theater with a faster pace, resulting in plays that only last one full night. At fifteen, John witnessed the latter and immediately fell in love. It did not matter to him that Kathakali tells only the stories of the Hindu gods from the great epics, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. Nor did it matter that most performances took place in Hindu temples, and included the actors paying obeisance to the temple gods. John left his school and his church education and devoted himself entirely to becoming a Kathakali actor.

For 9 years he studied the ins and outs of the form, at the prime school for Kathakali, the Kerala Kalamandalam. The full day, physically demanding days teach the actors techniques of controlling each part of their bodies, from head to toe. Mornings begin with eye exercises, continue with the study of abhinaya, the unique sign language used in Kathakali and Kudiyatam, and end with rigorous dancing. When he graduated, John was awarded an excellence award, and became the world’s first ever Christian Kathakali actor, and was awarded the honorific Kalamandalam John.He performed the Hindu plays for many years. When the opportunity presented itself he created a Kathakali play about the Christian saint who first came to the region from Syria. Despite controversy, he performed the saint without the elaborate make up and costume, in a simple monk’s outfit.

His wife Marie also shook things up in the Kathakali world, when she learned the art of Kathakali make up and began to prepare John for performances, (as you can see in the picture above) a process which takes three hours. She is the first and only Indian woman Kathakali make up artist.

John exhibits two things that impress me deeply, beyond the incredible talent and knowledge that come with 50 years of performing and teaching Kathakali. The first is a rare openness to experimentation and new creations, which remains rooted in this ancient theatrical form. And the other is the deep-seated openness around divinity that I have only witnessed in India. How could a devout Christian pay obeisance to Siva, Rama, Brahma, Vishnu or any of the other Hindu gods? How could he participate in a play written by a rabbi who considers the performance an offering to God? Because God is one.

The old Indian way is welcoming and inclusive of any and all gods. “Who, Jesus? Sure! Bring him into the temple! Adonai you said? An invisible god? Great, let’s put one of his symbols next to Ganesh.” This welcoming multiplicity comes from a deep understanding that God is simultaneously the most serious business we have, and a manifestation of human play. It’s so real that it goes beyond the categories we habitually use for reality. Using God to exclude or denigrate others is the ugliest type of idol worship.

My play, Pharaoh is in part an attempt to define what we mean by the phrase “one god.”

“What does it mean when you say ‘one and only God,’” Pharaoh asks Moses in one scene. After Moses scoffs at the question Pharaoh digs further: "So you're saying that everything we Egyptians believe in is a......"

"Fantasy," Moses answers.

This absurdly vain idea, that my imagining of God negates yours, has been bugging me since the first time I ever stepped into a Hindu temple, and was slapped with my people's centuries of guilt and prohibitions. I was sixteen and vulnerable to such guilt trips. And yet I quickly began to see how that exclusionary vision is being used not only for religious and cultural reasons, but for political purposes, with dire consequences.

Both monotheistic and polytheistic traditions can be either inclusive or exclusive, depending on your interpretation of the core idea of godliness in them. The current Indian government is taking an inclusive and playful faith tradition, and twisting it to exclude and humiliate Muslims and other faiths. Some Christians, Muslims and Jews around the world sin by interpreting the notion of one god as an exclusive and punishing “truth.” The faith I live by is a monotheism that is not threatened by other gods or notions of divinity, but raised up and buoyed by them. “Adonai Echad,” "God is one," means we are all one, a part of the all. The idea that “only my god is real” is, to my mind the opposite of the Torah’s charge.

Today, when John inhabits a character, he is in a glorious and unified command of his body. A decade of rigorous training followed by four decades of performing and teaching all over the world manifest in the spectator’s sense of watching a master at work. Countless times in rehearsal, Michael, Alysia and me have been swept into wonder watching John bring Pharaoh to life through movement.

Let us all take a page from Dr. Kalamandalam John in bringing true glory to God, through the open creativity, playfulness and inclusive understanding of the concept of God, and its expression through the wonder of the human body.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Pharaoh Sends Love

by Rabbi Misha

It has been fifteen years since I began obsessing over Pharaoh. It began in a tiny village in the south of India, a lush, tropical heaven by a river, where I had come to watch a play. It was a little longer than most plays I had seen with a run time of just over two weeks.

Chakyar Margi Mahdu as Ravana in the Asokavanikangam. Photo by Ranjith S

Dear friends,

It has been fifteen years since I began obsessing over Pharaoh. It began in a tiny village in the south of India, a lush, tropical heaven by a river, where I had come to watch a play. It was a little longer than most plays I had seen with a run time of just over two weeks. Every evening we would gather at the Kuttambalam, a small, roofed open air theater a couple minutes walk from the temple. The drummers would take their seat atop the giant mizhavu drums, a conch horn was blown, and the actor would appear onstage, in the elaborate costume and make up of the ten-headed demon king, Ravana. That is when the improvisation would begin. Using the unique sign language of the Kudiyatam theatrical tradition, he would remind us what happened yesterday, and then enact for us the next piece of the story, complete with hours-long diversions to paint the full picture of the associations and memories the story evokes in Ravana’s gorgeous mind. It might go on four hours. Usually a bit less, sometimes more.

The play was called the Asokavanikangam, or Asoka Tree Garden, and told of the time when Ravana kidnapped the goddess Sita, wife of Rama, and did everything he could think of to convince her to sleep with him. It didn’t work. Ravana was thrown into a crisis. Never before had he been prevented from accomplishing a task, fulfilling a desire. Several times during the course of the play he recalls the time when his charioteer told him they would have to travel around Mount Everest (called Kailasa in the play), because it’s too high to go over. Ravana refused to accept this indignity. He steps off the chariot, and though it might take him half an hour of stage time he eventually succeeds in picking up the mountain and moving it aside (not before some agile juggling). Now, however, he is faced with an obstacle he cannot surpass, in the form of Sita’s pure devotion to her husband.

Over the fifteen nights of the play we watched Ravana lose his powerful, charismatic self to the experience of limitation. While he would sit sadly on the floor reckoning with his inability and his tremendous lust, the theater would be visited by fruit bats, who would fly in and flatten themselves against the ripening bananas decorating each side of the stage.

This is what religion is meant to be. An encounter with human creativity, with joint brokenness, with the interconnected depths of good and evil, with the inconceivable beauty of life.

I came out of that experience with two convictions, one conscious and the other not yet. Consciously I decided to write a play that would offer the gift of falling in love with a mythical villain to a Western audience. A few days later I landed on the great enemy of the Hebrews, symbol of ego, stubbornness and cruelty to all three major monotheistic faiths, Pharaoh. The next day I arrived at the central temple of the great ancient Tamil city of Tanjavur. After offering gifts and prayers to the god Siva and his bull Nandi, I parked myself with a notebook in a corner of the temple, and out came the first scene, where Pharaoh battles Death, and wins.

Since then I have been spending far too much time with my beloved Pharaoh. I have learned of his genius, his relationships with his wife, daughter and son, his blind spots and his prophetic wisdom. I gained insight into the theological-political duel between him and Moses. I have come to see the destructiveness in the flat story of good and evil that our tradition attempts to maintain. And I’ve encountered through him my own hints of divinity, and my deep, human limitations.

After a path I could have never imagined, the play is set to open in a few weeks, with a South Indian master of Kathakali - the faster paced dance theater sibling of Kudiyatam - in the lead role, who will be dressed in the same costume and make up as Ravana was in that play I saw all those years ago. I’ll tell you more about this incredible actor and maybe more about the theological battle at the heart of the play in the coming weeks. And hopefully about that unconscious conviction I mentioned earlier as well. It’s rare for a playwright to have an opportunity to lay out the story of writing the play, and the ideas they are working out in them. I’m excited to take these next few weeks until the opening to dig into some of the driving questions behind my rabbinical and theatrical path, as they found expression in the writing, acting and production of Pharaoh.

For now I wish you a peaceful Shabbat. Pharaoh sends his love. Might it be time to open your heart to him?

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

The Angel in Your Dream

by Rabbi Misha

One of the greatest polemical books in the Jewish canon is The Kuzari, a medieval book by Rabbi Yehudah Halevi. The book tells of the idol-worshipping King of Kuzar, who has a recurring dream, in which he is visited by an angel who tells him:

Dear friends,

One of the greatest polemical books in the Jewish canon is The Kuzari, a medieval book by Rabbi Yehudah Halevi. The book tells of the idol-worshipping King of Kuzar, who has a recurring dream, in which he is visited by an angel who tells him:

כוונתך רצויה אך מעשך אינו רצוי

Your intentions are desired, but your actions are not desired.

The king understands that God is both pleased and displeased with him. He must keep his intentions of serving God, but change the ways in which he does it. The king then engages in philosophical, religious and theological conversations with a philosopher, a priest, an Imam and a rabbi, in an attempt to figure out which practice he should adopt.

At the heart of the book is a challenge to us all: can we ask ourselves the question posed by the angel. Where are our intentions good, but our actions not?

The question seems to me the stuff of dreams. Something that can gnaw at our subconscious at night and unnerve our days. But there have been times in my life, in which I've managed to locate a discrepancy between action and intention, moments in which I was telling myself I am doing one thing, but in effect doing another. During those times it is as if my body is serving someone else. And perhaps the strangest thing about it is that while it does that, buried in the back of my own mind is the full knowledge that this is taking place; that I am setting aside the connection between my mind and my body for a time, and living with the pain of that split.

Last week I related some of my military service, and several of you expressed interest in that experience. In my own limited conscious understanding of my self, there is no other experience I've been through that better embodies the angel's axiom about intention and action. The intention was to give back to the collective, to do my part, to protect life, to participate in the shaping of our world. The action was to uphold an occupation of a militaristic nation state.

People really do want to do good. I believe that about almost every person. I believe that about myself, and I believe that about you. But I know that our actions don't always result in goodness. The angel asks: Where are we not acting out our true selves? Where are our intentions taken hostage by someone else's agenda? Where are we supporting causes and projects that bring about our internal corruption or our national combustion? Where are we living someone else's life?

If we can find those places we might be able to unclog the channels between our pure intentions and our misguided actions.

If we can pose these questions to our waking, and more importantly perhaps to our dreaming selves, maybe we will be able to enjoy the deep satisfaction of having both our intentions and our actions desired by that mysterious force who keeps consciousness flowing.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Happiness in Tough Times

by Rabbi Misha

I always remembered my time in the Israeli army as depressing.

Living Theatre legend, Tom Walker, who died last week, performing a strike-support play with the company in Italy, 1976

Dear friends,

I always remembered my time in the Israeli army as depressing. Beyond the fact that soldiers are constantly counting backwards the days until they go home, and until their final release, I felt my time in the South of Lebanon as a moral compromise about which I was deeply conflicted. The idea of being a part of any army felt antithetical to who I am. And following the orders of the terrible and cruel man at the top of the pyramid – then first term Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu - didn’t help. Imagine holding a rifle that you have to shoot whenever the leader you hate most says shoot and you’ll understand the situation I was in.

Soldiers were dying around me, while rockets kept flying into northern Israel, the stated reason for our presence there. More depressing was the state of the local population, with which I had significant contact, since my base in Marj Ayoun served as the regional headquarters of both the IDF and the South Lebanon Army, a kind of puppet army of Israel. The locals had no prospects, between the allegiance they had to show the IDF to survive, and the knowledge that one day the Israelis will leave, and Hezbollah will take over and accuse them of collaboration with the enemy. I left in 1999, and indeed a year later that’s exactly what happened.

A few years after I was released, I visited my commanding officer, long out of the army, and like me pursuing a career in theater. Sitting in his apartment in Jerusalem, he showed me a photo from our service. Five of us were in his office in our uniforms, each of us with smiles on our faces. Mine was the biggest smile in the photo. The photo rattled me. It brought back the experience of the day to day there, the friends I hung out with, the exciting sense of moving around, hitchhiking up to the northern border, bussing down to see my girlfriend in her kibbutz near Haifa, reading Hemingway under the sole fig tree in the base, drinking Lebanese black coffee (rivaled only by Italian espresso in Italy) as I gaze out at the high mountains leading up to Syria in the east, and the Beaufort, a majestic Crusader fort above the Litani Valley to the west. That single photo shattered my conception of my time in the army. I saw it and knew that even within the painful circumstances, I had plenty of moments of happiness and contentment.

I find myself wandering back to that time in search of ways to be content during this period. The war rages on. The insanity of the death toll and the destruction of Gaza weighs heavy. The hostages that are still alive are not back. And that’s before I even go into my more mundane anxieties and painful events here in New York. Anyways this stage of winter has a way of getting me down.

And yet – this evening begins a new moon.

This moon of the Hebrew month of Adar brings with it a command:

משנכנס אדר מרבין בשמחה,

“Once Adar begins, we do lots of happy.”

More than that, this is a leap year in the Hebrew calendar, which means we get two months of Adar. Do you feel that kick in your ass to step out of your malaise? Those are your ancestors saying “snap out of it! Life is short.” It’s time for us to actively seek happiness, relaxation, peace. We deserve it.

Shortly after I came out of the army and engulfed myself in the New York downtown arts scene, I met a theater troupe that had just come back from a series of workshops in Lebanon. When they were down south, in what was by then Hezbollah territory, they created an anti-war play in the notorious Al Hayyam prison, where the IDF would imprison and often torture suspects. Led by the daughter of a rabbi, The Living Theatre is a pacifist-anarchist group that was in the business of taking the brokenness of the world and the pain in their souls and transforming it into borderless, theatrical love. My years with the company taught me a lesson about joy: it’s not about ignoring pain; it’s not about ignoring the world; it’s not about ignoring what you feel commanded to do. Be with it, and see through it into God, into humanity, into the dancing soul of the universe.

I hope you can all join us this evening for Shabbat, where we will follow the tradition of finding joy on the narrow bridge. John Murchison, a wonderful Qanun player will be joining Yonatan and Daphna in bringing the music, and rabbi and activist Miriam Grossman will join me in laying out the ideas that might lead us to finding happiness and peace.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha