Sort by Category

Pst-Dobbs

by Rabbi Misha

In 1955 in Queens, NY, a small crowd gathered to say Kaddish for recently deceased Cyral Cottin.

Dear friends,

In 1955 in Queens, NY, a small crowd gathered to say Kaddish for recently deceased Cyral Cottin. Her fifteen-year-old daughter, Letty was told that she would not count towards the minyan because she was not a man. Letty’s response was to cut herself off from the public sides of her Jewish faith. For fifteen years, she would not affiliate with any synagogue or Jewish organization. At home, she continued to maintain certain rituals. “I wasn’t going to let my alienation from my father’s religious institutions cut me off from the rituals associated with my mother and the home-based Judaism in which my heritage felt ... most real.”

Within twenty years of her mother’s death, Letty would become an enormously influential figure in the Feminist movement. In the seventies, she joined with Gloria Steinem and other women to found Ms. Magazine. For over fifty years Letty has been at the forefront of the fight for women’s empowerment and safety.

In a way, these days it feels like we’re back at square one when it comes to women’s rights. We’ve stood on the shoulders of women like Letty for so long. We aren’t carrying our weight. How long could we expect them to keep carrying us? And yet, here we are, the protections we’ve taken for granted stripped away. Women’s safety is so foundational that when it is at risk all other marginalized groups suffer too.

In the face of all of this, someone like Letty chooses this moment to tell her bravest story yet: Shanda, the story of her life, her ancestors, and the way that shame and secrecy worked to control and suppress the narrative. Instead of lashing out at our broken world, Letty looks inward, at her own story, at the missteps of those closest to her, and even at her own. She tells her story in a way that makes you want to tell your own. To say more truthful things. To be a little more honest about who you are, and where you come from. I can’t think of anything more urgent right now.

Letty’s incredible story will be on full display on May 15th, when she joins us at our Kumah Festival event. I’m especially excited that Erika, my far better half, will be interviewing Letty. Erika’s work in restorative justice is rooted in untangling shame, secrecy and ancestry, and she’s also no stranger to sharing her own private pain as a way to inspire change.

For those of us who can make it, this will be a privilege to hear from Letty, an important Jewish thinker who continues to change our world for the better. I’m sure that this intergenerational conversation between two strong women will help us understand our role in this post-Dobbs moment.

I hope you'll be able to join us!

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Grief Demands Company

by Rabbi Misha

This past Tuesday was Yom Hashoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day. On Monday, The New Shul will join with dozens of other organizations to sponsor the Joint Israeli-Palestinian Memorial Day Ceremony, and on Tuesday we will celebrate Yom Ha’atzmaut, Israeli Independence Day.

Dear friends,

This past Tuesday was Yom Hashoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day. On Monday, The New Shul will join with dozens of other organizations to sponsor the Joint Israeli-Palestinian Memorial Day Ceremony, and on Tuesday we will celebrate Yom Ha’atzmaut, Israeli Independence Day. I’m excited to mark these special days with you all this evening at our Zoom Kabbalat Shabbat, as well as to share with you some reflections about my recent trip to Israel.

I had the honor of being asked by the organizers of the Joint Ceremony, the largest Israeli-Palestinian peace event in history, to put together some Jewish sources that reflect our tradition’s drive toward such an event. I’m glad to share it with you today.

Grief demands company. A mourner needs another to comfort them, as the Talmud says:

אין חבוש מתיר עצמו מבית האסורים, “A prisoner cannot take himself out of a prison cell.”

The Brachot tractate of the Talmud offers a series of stories about rabbis who help their fellow rabbis out of sickness and grief. They all end with the same phrase: “’Give me your hand.’ He gave him his hand and he stood him up.” The joint Israeli-Palestinian Memorial Day Ceremony is an act of mutual support to help us all stand back up, in order to find the strength to fight for a safer and better life in the Holy Land.

The final story in this Talmudic series involves a father who lost ten of his sons. After the tenth one died, Rabbi Yochanan began going everywhere with one of the bones of his tenth son.

In this story he finds Rabbi Eliezer in bed in a dark room, crying.

א''ל אמאי קא בכית אי משום תורה דלא אפשת שנינו אחד המרבה ואחד הממעיט ובלבד שיכוין לבו לשמים ואי משום מזוני לא כל אדם זוכה לשתי שלחנות ואי משום בני דין גרמא דעשיראה ביר א''ל להאי שופרא דבלי בעפרא קא בכינא א''ל על דא ודאי קא בכית ובכו תרוייהו אדהכי והכי א''ל חביבין עליך יסורין א''ל לא הן ולא שכרן א''ל הב לי ידך יהב ליה ידיה ואוקמיה

Rabbi Yochanan said to him "Why are you crying? Is it because of the Torah that you can't study today? If so, we've learned: 'one does more and one does less, as long as their heart is oriented toward heaven'. Or is it because of your poverty? If so, know that not every person merits both wealth in Torah and material wealth. Or Is it because of your children who have died? If so, this is the bone of my tenth son."

Rabbi Eliezer said, "It’s because of this beauty that will disintegrate into dust that I'm crying."

"For this,” said Rabbi Yochanan, “surely it's worth crying." And they cried together.

Eventually Rabbi Yohanan said, "Are you enjoying your suffering?"

Rabbi Eliezer replied: "Neither the suffering nor its reward."

He said: "Give me your hand."

He gave him his hand and he stood him up.

None of us want to suffer. The joint ceremony offers us all the opportunity to grieve together, and then reject the competing narratives of suffering. But transcending the narratives of fear and division takes courage. Death can bring us together, but more often it tears us apart. The Mishna in Avot asks: “Who is brave?” The hero is not one who excels in battle, but one who is able to subdue his instinct toward revenge and hatred.

איזה הוא גיבור? הכובש את יצרו״”

Who is a hero? One who subdues his inclination.”

This is the work that the Combatants for Peace have been engaged in for many years.

Avot of Rabbi Nathan takes the question one step further.

“Who is the hero of heroes,” the rabbis ask. “The one who turns his enemy into his lover.”

"איזהו גיבור שבגיבורים – מי שעושה שונאו לאוהבו”

This is the work that the Bereaved Parents Circle has been engaged in for decades. These two organizations have invited us to take part in this brave work for the sake of our future.

The Jewish tradition teaches that in the future separation between one group and another will be erased. Most people know the Talmudic maxim: “Whoever saves one soul in Israel, it is as if they saved the entire world.” But Maimonides brought down a different, more universal phrasing. Israeli supreme court justice Mishael Cheshin chose to quote Maimonides in his 1991 decision, convicting a Jewish man of the murder of 7 Palestinians.

אדם - כל אדם - הוא עולם לעצמו. אדם - כל אדם - הוא אחד, יחיד ומיוחד. ואין אדם כאדם. מי שהיה לא עוד יהיה ומי שהלך לא ישוב. וכבר לימדנו הרמב"ם על ייחודו של האדם (ספר שופטים, הילכות סנהדרין, יב, ג): "נברא אדם יחידי בעולם, ללמד: שכל המאבד נפש אחת מן העולם - מעלין עליו כאילו איבד עולם מלא, וכל המקיים נפש אחת בעולם - מעלין עליו כאילו קיים עולם מלא". הרי כל-באי עולם בצורת אדם הראשון הם נבראים ואין פני כל-אחד מהם דומין לפני חברו. לפיכך כל-אחד ואחד יכול לומר: בשבילי נברא העולם.

“A person – any person - is a world unto its own. A person – any person – is singular, unique and special. And there is no person like another. Whoever was will not be again, and whoever has gone will not return. And Maimonides has already taught us about the uniqueness of each person (Book of Judges, Rules of Sanhedrin, 12, 3): “Adam was born alone in the world to teach us that whoever destroys one soul in the world it is as if he destroyed the entire world, and whoever saves one soul in the world it is as if they saved the entire world.” Each of those who came to this world in the form of Adam, is a created being. One’s face is always different than another. Therefore, each and every person may say: for me this world was created.”

Psalm 19 offers us the phrase ״צדקו יחדיו״ “Together, they were just.” The justice that we see separately, the psalmist suggests, is less complete than that which we can find together. This Yom Hazikaron, let us join together to grieve, stand each other up, and support one another in the fight for a viable future in the Holy Land, a future of care and justice for all.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Prayers From Rikers

by Rabbi Misha

“My son plays soccer right over there,” Shira told us as she drove us into the parking lot on route to Rikers Island. She parked the car, and our small delegation of rabbis and activists picked up our passes that will allow us to drive over the bridge and enter the jail.

Dear friends,

“My son plays soccer right over there,” Shira told us as she drove us into the parking lot on route to Rikers Island. She parked the car, and our small delegation of rabbis and activists picked up our passes that will allow us to drive over the bridge and enter the jail. The four of us, Shira, Rabbi Margo and Rabbi Becky from Truah and me had come, one week before Passover, to join the prayer services and teach Torah to the Jews who find themselves there. Back in the car we show our passes at the entrance to the bridge that goes over the water from Queens. As we drive across, I’m struck by the massive infrastructure that was built and maintained to create this jail. Across the bridge we’re stopped at a few other checkpoints to see our passes and finally allowed in.

It’s a sprawling place with a number of different facilities. We are going to the Anna M. Cross center, which houses approximately 2000 people. Pretty much everywhere you look on the island you see barbed wire, so much of it that in certain places it almost looks like an art exhibit. We find Rabbi Gabe and the rabbinical intern sitting at a small picnic table, and the four of us guests gather around. Gabe has been one of the three Jewish chaplains on the island for five years. The two of them give us some information about how things work there, describe the living conditions of the people incarcerated there. Most of them live in giant rooms with 50 other people. Those with acute mental conditions stay in a different part of the center in smaller rooms, and as soon as they show any sign of improvement, are sent back to the main dorms.

When we enter the Center we show our passes and our IDs, surrender our phones for safekeeping, go through an airport style metal detector and walk-through. Someone remarks that it feels like a high school other than the bars here and there. Rabbi Gabe describes the quarter mile long hallway that goes towards the dorms. He tells us that there are a few hundred incarcerated people on the island who identify as Jewish, but he doesn’t expect more than ten people at the prayer service, in part because there isn’t enough staff to escort people from the dorms over to the chapel. They used to be allowed to walk on their own sometimes, but that practice was ended during Covid and doesn’t seem like it will be restored. Staffing has been a serious problem there, which became impossible during Covid. This has resulted, in addition to certain limitations, in close to one preventable death in the jail every two weeks in the last few years.

We enter the chapel through the back door, near the small bookshelf they call the library. We marvel as Rabbi Gabe pushes the Jewish part of the ceiling-height three-part stage of sorts into place. The room changes from a church to a synagogue. Within a few minutes, the pews are filling up by around 10 people who came to pray.

Rabbi Gabe had mentioned that the center houses a lot of people with mental health issues, and indeed, this is quite clear about several of them the moment they sit down. We sit among them and say hello. A few of them had grown up in religious Jewish settings, some seem to have begun identifying themselves as Jews in Rikers, and others years earlier. They’re all there to pray, most with yarmulkes on their heads. I am struck by the openness with which they speak about their situation, sharing personal details, some even including their mental diagnoses. I am beginning to understand how important this one weekly prayerful gathering is for these people, who seem starved for meaningful conversation and connection.

As Rabbi Gabe begins the prayers, One of the more orthodox Jews, a sweet, young man named Chaim, parks himself in one of the corners, and begins to put on Tefilin. He invites anyone else who’d like to join him, offering to help them wrap them on. One does, and I watch Chaim lovingly take his friend through the ritual.

Rabbi Gabe leads us through the prayers. Ashrei, Shma, V’ahavta. He then pauses the traditional prayers, and invites people’s personal prayers. A couple hands of hands go up. A young African-American man, who had been talking to himself from the moment he sat down, speaks first. He delivers a heartfelt, straightforward and moving prayer. He asks for a more compassionate justice system. He prays for a particular procedure called Exam 930 to happen much, much earlier in the process. We will learn later that this is a procedure in which a person can be deemed mentally unfit to serve in jail or prison. “This should happen in the first interview,” he says. “For most people it doesn’t take more than a minute to see what their mental condition is like.”

John speaks next. “I was abused my whole life,” he opens. He shares that he suffers from ADD, ADHD, and severe depression. Rabbi Gabe gently offers a sentence or two to each one who speaks, saying things like “we don’t know the reason why we suffer, but I wish you that God spreads the shelter of peace over you.“ Avi tells us he was homeless before he was arrested. He speaks about being on the island for over five months and having trouble making friends, in part due to depression. Rabbi, Gabe tells him that he prays for him to find companionship and friendship. Drake speaks about meditation, and how he meditates often, during all kinds of situations, sometimes, as he walks through the hallways he is meditating. “You can meditate anywhere,” he offers.

We speak The words of Psalm 121. “I raise my eyes to the mountains, from where will my help come? My help comes from Adonai maker of sky and earth.” Then the Rabbi invites me to lead the teaching I had prepared. “There’s a line in the Haggadah, in which we are told that God heard us,” I tell them, and ask: “What does would it mean to be heard by God?” A lively discussion ensues about the different verbs used in the Haggadah: God hears the cry, God sees the suffering, God knows.

“God seeing me is like when I look at myself from the outside. God knowing me is more intimate, from the inside.” Drake has a different take: “God knows the totality, everything, and my minuscule place within it. God sees is a seeing of my particular situation.”

For half an hour we discuss, debate, listen and read until I invite them to close the discussion by reading together the blessing from the Amidah: “Blessed are you, Adonai, who hears our prayers.” Barukh Atah Adonai Shomea Tefilah.”

The guards announce that it’s time to go, and we say a warm goodbye to our study partners, who are genuinely appreciative of the fact that we came, of what we offered, of the time we shared together.

As we walk out, Rabbi Gabe flips the stage back towards the Christian side, and we walk back out to the hallway. We are passed by more groups of people in drab, brown outfits and officers in blue escorting them around. We receive our phones and IDs back and walk out, back to that same little picnic table on the grass under the barbed wire. We grapple together with questions of complicity, with the tremendous desire for change, with the question what victory might look like. Closing Rikers would be a good start, but those who work there know that even if and when that day will come, the carceral system will continue to act in painfully cruel ways to uphold the injustice present in our society at large. We speak about how clergy that work in these kinds of spaces need support, and what that support might possibly look like. Finally, we say goodbye, get back in Shira‘s car and drive over the bridge back to Queens. Looking at the airplanes taking off from LaGuardia. Just a short 10 minute swim from Rikers, I feel like that’s an especially mean touch, to place that jail right in front of the airport.

I walk out of this day with appreciation for those who work daily to offer support to the people living on the island. I feel the camaraderie of the many in the struggle who work against the odds to create a more caring world. I leave with some conclusions of the political and social type: Another way to work with people with mental problems exists. The mayor’s criminalization of mental health issues, and the many such people living on the streets is wrong. We do not have to be this cruel. But more importantly for me, I leave feeling like I have a lot to learn about prayer from people like John and Drake and Avi, and the rest of those beautiful, troubled people we met at Rikers. The sadness I felt as I heard their stories might be the beginning of a different kind of prayer, a real prayer, and it may even be the only kind of prayer that God can hear.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

24 Hours on the Streets of Jerusalem

by Rabbi Misha

24 Hours on the Streets of Jerusalem

Dear friends,

A couple of hours after arriving in Jerusalem I went out for an evening stroll with my mother and my son. We’d walked half a block when we found a group of men waiting on the street for two more people to show up to complete a minyan. Certain street corners of west Jerusalem become synagogues these days for half an hour twice a day. We stopped to pray the evening prayer, enjoying the quiet ancient murmurings with them, and continued on our way. We expected a quiet evening.

We walked over to to Aza Street and sat down in a sidewalk cafe for a drink. As we’re chatting, a crowd began to gather across the street. More and more people with Israeli flags coming in from all directions. “He fired the Defense Secretary,” we hear, “It’s a spontaneous protest.” The young crowd gets the protest started with chants they have been leading for weeks. “Democracy or rebellion!” Within minutes the crowd has grown to hundreds and the intersection has been shut down. Jews of all types and ages are singing together: “If there will be no equality we will overthrow the government – you’re messing with the wrong generation!”

The energy is infectious. People are focused, determined, and most surprising to me, happy. As am I, swept out of my despair and cynicism into this sudden demand for sanity.

My skepticism is real. I chant “De-moc-rat-ya” with the full knowledge that this country has never in its history been a true democracy for all its citizens. Until 1970 all its Arab citizens lived under military rule. Three years before that ended, the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza began, a brutal military occupation lording over millions of stateless, rights-deprived Palestinians, most of them refugees, many of whom have been forced out a second time even from their places of refuge. It is in large part for the Palestiniansp, now in their 58th year of occupation that I join these protests. They are the ones who will suffer most if the separation of powers in Israel is demolished, as these laws the ultra-right is working to pass are designed to do.

Another endangered population here, which would certainly suffer as well are those known as “smolanim,” or “leftists.” Right wing assailants have brutally attacked protesters, a continuation of many years of vilification (despite the fact that many of the protesters are right wing.) Driving back from the airport a few hours before this protest my father told me he doesn’t want to end his life in prison. “And that’s not a remote possibility.”

At the protest, I’m happy to see several protesters holding signs saying “There is no democracy with occupation.” This tells me two things: on a personal level, I can bring my full self to this protest. I can use the word “equality” as a prayer for full human equality - as I understand the Torah to demand - and not just the compromised equality that has accompanied the state up til now, as I think many of the protesters understand it. On a public level this tells me that the anti-occupation bloc has been accepted as a legitimate part of this protest; that the understanding that the protests and the occupation are inextricably linked is sinking in.

It’s 10:45pm and the protest has grown tremendously. My son, Matan and my mother have returned home but I couldn’t leave. Now I am marching through the streets of my childhood with thousands of people. I’m walking next to two young poets, who chant a rhyming couplet they make up on the spot, and we all repeat it:

צאו מהמרפסת – המדינה קורסת!

Get off that balcony – the country’s falling apart!

צאו מהסלון – מנעו את האסון!

Get out of your living room – prevent the disaster!

צאו מהמטבח – המדינה בפח!

Get out of your kitchen – the country’s in the garbage!

צאו מהאמבטיה – הצילו ת-דמוקרטיה

!Get out of the bathtub – save democracy!

There are Israeli flags everywhere, torches, chanting, and now we’re in front of the Prime Minister’s house shouting “Shame! Shame! Shame!” More and more people join this nighttime rebellion. We hear that the Ayalon highway in Tel Aviv is also closed down, as well as the main thoroughfare in Haifa. Eventually, I give in to my jetlag and make my way home. My parents breathe a sigh of relief as I walk in the door, since they heard that protesters broke down the barriers to the PM’s home, and there were arrests and injuries.

The following morning the papers are reporting that Netanyahu is about to capitulate. The entire country will be on strike. The main workers union, the airport, universities, high school students council, the banks, reserve soldiers, everyone is on strike until this plan is called off. But Netanyahu is held hostage by his openly racist coalition partner. We walk over toward the Knesset, where protesters from around the country are heading. All roads lead there today, as is obvious from the blue and white flags bobbling in that direction wherever we go.

Not everyone agrees with us though.

“Take that kipa off your head,” a cab driver yells at me, “you leftist sons of ——-!” Someone offers us a flag. I demure, but Matan takes it and we walk by the national library and are soon engulfed in an incredible multitude in front of the supreme court. The energy is that same infectious celebration from the previous night. There is an enormous amount of people, probably in the hundreds of thousands, each with their own signage or t shirt. Somehow, we find my brother, two of his kids and my father. I’m standing next to my nephew’s wheelchair taking in the sounds, when his care taker, Yaron says: “Radical aliveness.”

Among this huge multitude are smaller groups with their own agenda within the agenda. I pass by the socialist gathering with their red flags, the LGBTQ group with their pink and rainbow flags, the military group with their black and blue flags, and stop in front of the largest of these mini-groups, the anti-occupation gathering. Here there are Palestinian flags, and big white banners in Hebrew and Arabic. Some people are holding signs that read: “From the river to the sea all the people must be free!” These are the best organized of all the protest groups, since many of them have been gathering in Sheikh Jerrah every Friday for the last decade to try to protect the Palestinian residents there from the takeover of Jewish supremacists. They are organized in a big circle with twenty to thirty drummers. In the sea of blue and white flags I finally feel truly at home in the embrace of a richer, less compromised form of justice. “From Sheikh Jerrah to Bil’in Hura Hura Falestin!” (Arabic for: Freedom Freedom for Palestine!)

There is one Israeli group sadly absent from this protest, and that is the Palestinian citizens of Israel. The sea of Jewish stars, the stomping down in the early protests against the Palestinian flags, the requests from the protest organizers that Arab leaders not come so as not to alienate the center and right wing protesters, have all done their work.

As I see it, the only chance for lasting democracy here is a meaningful partnership between Jews and Arabs. If Israel truly is what its Declaration of Independence says it is, a place of equality for all that retains a Jewish character, then, amazingly, it is the Palestinian citizens of Israel who hold the key. Without their support the demographics of the country are such that a Jewish theocracy is more likely, or an even more unequal ethnocracy. They are another reason I join these protests. The suggested laws could easily lead to outlawing non-Jewish political parties, and it’s not unlikely that the next step would be revoking their right to vote.

It’s hard to move in this mass of happy protesters, but we somehow make our way down toward the Knesset, where we hear some speeches. On the way I bump into old friends, and into one of my commanding officers from the army, Yair Golan. When he was deputy chief of the IDF he warned that processes taking place in Israel are reminiscent of 1930’s Germany. Now he is a leader on the left. He shakes my hand warmly, his smile full, this strange complex happiness we are engulfed in shining out of him.

I’m wearing on my shirt the word שויון, “Equality” in Hebrew. Shivyon is a modern word that hearkens back to a word from a verse in the Psalms: שויתי יהוה לנגדי תמיד “I place YHVH before me always.” The idea is that no matter what you’re doing, it’s as if you are constantly cognizant of God as your guiding purpose, seeing God in front of your eyes. The word Shiviti, “I place,” or “I imagine” is where the Hebrew word shivyon comes from. Shiviti is like placing all those created in God’s image in my sight, as a constant reminder of our humanity, and our responsibility. A country of people who do that would be my kind of Jewish State.

The speaker is talking about this governments war on women: “In the three months since the government formed, nine women have been murdered: More than the number of women in the Knesset,” she says. The government has shut down laws meant to protect battered women, and this proposed legal revolution is certain to further reinforce the patriarchy. “The only time the government cares about women who get murdered,” she says, “is when it is an Arab killing a Jewish woman.”

Eventually we make our way out of the protest. In the streets of nearby Bet Hakerem most of the people walking by are protesters. The falafel stand is packed with them. Even the trains and buses from around the country are filled with people singing chants of revolt.

That evening at my brother’s place outside of Jerusalem, as we gather in front of the television to watch Netanyahu’s speech, my sister in law tells her kids: “This is a liar.” Like much of the country, this time has brought her to the streets, even though she normally isn’t especially active politically. My seven year old nephew says: “He’s like Pharaoh.” As soon the PM utters his opening words, “Three thousand years ago,” my sister in law asks whether we could turn it off. This is the level of tolerance in much of the country for the man who’s been Prime Minister for most of the last decade.

He starts by comparing “both sides” of the country to the mothers who came in front of King Solomon, each claiming the baby is their own. He denigrates the protesters against him and smiles when he speaks of his pride in those who came out in his favor, holding such signs as “Leftist traitors,” and “Stop the dictatorship of the Supreme Court.” The PM’s clear implication tonight is that his side is making the sacrifice of postponing the laws, because they are the true mothers of this baby called Israel, so they won’t let this country fall apart. The wise King Benjamin sees the truth.

Despite this temporary victory, the happiness of the protest, and the hope it brought are dissipating. Nobody trusts the PM, not even the members of his cabinet. The future looks dire. He kept his coalition from collapsing by promising to start an extra governmental militia led by the most violent and extreme cabinet member. One of the chants at the protest was “We are not afraid.” That may be true while we’re there, but the truth is that most of the protesters came precisely because they are seriously fearful for their future. This is another reason why I protest. Israel, built with huge sacrifices of blood, sweat and tears to offer a necessary safe-haven for Jews is on the verge of unravelling. It is not the idealistic vision I was sold as a kid, nor is it a beacon of Jewish ingenuity. It is a nation state, as vicious as any other, which is the beautiful place where my family and many close friends live. Right now the only hope for preventing it from devouring itself are these protests.

I come out of these historic 24 hours, and the few strangely quiet days that followed them with a distinct faith in the capacity of people in this country to activate. The government still plans to pass these laws. The demonstrations continue. But the majority has, for now prevailed, and that is no small achievement for any protest movement.

One of my favorite biblical words is Kumah, rise up. Moments such as these are Kumah moments. They carry the breathtaking ecstasy of freedom. This Shabbat Hagadol, the great Shabbat before Passover, we will raise the Torah and sing:

קוּמָה יְהוָה וְיָפֻצוּ אֹיְבֶיךָ וְיָנֻסוּ מְשַׂנְאֶיךָ מִפָּנֶיךָ

כִּ֤י מִצִּיּוֹן֙ תֵּצֵ֣א תוֹרָ֔ה וּדְבַר־יְהֹוָ֖ה מִירוּשָׁלָֽ͏ִם׃

Rise up YHVH and scatter your enemies,

Let the haters flee from before you

For Torah comes out of Zion,

and the word of YHVH from Jerusalem

Let the word of radical aliveness rise up from Jerusalem and bring safety and joy to all who share and love this land.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Women's Torah

by Rabbi Misha

Some words from our Resident Scholar, Dr. Lizzie Berne DeGear.

Dear friends,

As promised, some words from Dr. Lizzie Berne Degear, our scholar in residence this year. Lizzie and I will be leading a special interfaith Shabbat service this evening at First Pres with some amazing guests from other faiths. I hope you can make it.

Rabbi Misha.

Happy Women’s History Month from Lizzie Berne DeGear, our esteemed Scholar in Residence!

I’m about half way through my year as scholar-in-residence with the New Shul, and I’ve been loving it. Engaging with many of you at services, celebrations, and chevrutahs has been enriching and downright enjoyable. I hope to see you at our interfaith liberation Shabbat this evening at First Presbyterian Church at 6:30pm. Some women friends of mine will be joining us to share their powerful experiences of liberation within various faith traditions, including Catholic, Muslim, Hindu and Aboriginal.

Today, as a self-described feminist of faith, I’m thrilled to be engaging you here as I reflect on the importance of Women’s History Month.

“Women’s history” is not just about highlighting women in history, it’s about bringing women’s focus to our histories and revealing truths that have been obscured. This March can be a time to wake up to all the ways that “his-story” has shaped our limited understanding of our world. It’s an opportunity to expand our lens to include her story… and her story… and her story.

I’m particularly fascinated by the impact of these expanded lenses on scholarship. From archaeology to zoology, there is a paradigm shift underway. Over the past decades, as more and more women have had access to higher education in their chosen fields, slowly but surely women have been able to mentor the next generation of scholars. Women have been working together as colleagues, and women’s ways of knowing are beginning to shape each discipline. The patriarchal assumptions that have had a grip on virtually every form of academic study are slowly (oh, so slowly) dissolving into new ways to understand and interpret our past and the world around us today.

I get a thrill every time I come across these new ways of telling the stories that constitute scholarship. I’m thinking of the work of archaeologist Elizabeth Wayland Barber, author of Women’s Work: the first 20,000 years. On excavation sites in the 1970’s, she was the only one among her archaeology colleagues who had experience in weaving and sewing. She saw clear links between patterns that appeared on Bronze Age Mediterranean pottery and familiar weaving patterns. After she was told that there was no way the technology for weaving could have existed that early, she spent the next seventeen years researching and making sense of data that had been ignored. Thanks to her we now have a window onto the extensive technologies of prehistoric textile manufacturing.

I’m thinking of the radical theoretical work of physicist Karen Barad, author of Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. As a feminist thinker, Barad has introduced an approach to physics that is a game-changer, upending assumptions baked into Western scientific theory.

So, here at the New Shul, how can we celebrate Women’s History Month? Well, for starters, we can revisit any of our favorite subjects and ask ourselves: How are feminists and womanists looking at this subject these days? We can follow that curiosity and see what new vistas open up when we revisit a favorite subject, prod it a little, and take a closer look.

And, of course, we can bring this new lens to the subject of our Jewish history. We can honor that there is a major stumbling block inherent in our Jewish authoritative texts. Most of our Torah (the first five books of the Bible) and our torah (all of the written teachings and laws that hold a place of authority in Judaism) consist of men in our past writing about what men in their past wrote about. It can be a very limited lens on our vast Jewish story.

Grammatical fact: the rarest verb form in the Hebrew Bible is the third person feminine plural. This is because the men who wrote those texts were not focusing on the wisdom that emerged from the female collective. And, quite frankly, they didn’t have access to that wisdom. But that doesn’t mean such wisdom didn’t emerge and thrive during every moment in our Jewish history. It did! It does! Women’s collective experience and wisdom are absolutely part of our Jewish story, dating all the way back to its beginnings. Discovering this wisdom and experience, listening to our female ancestors, and receiving the bounty they still hunger to share with us has become a passion that drives much of my scholarship. There is so much there to discover! I take seriously the admonition that opens the book of Proverbs: “Forsake not the torah of your mother” (Proverbs 1:8).

As we approach Passover, I have been taking a closer look at Miriam. Following the clues, I am beginning to discern a whole branch of ancient Jewish knowledge that invoked her leadership, bringing focus to plant medicine and healing. More than a sister with a tambourine, was Miriam our earliest Jewish doctor?

As Judy Minor, the head of our New Shul va’ad, puts it: Every week of Torah study is an opportunity to tap into our Jewish herstory. As we study, and as we are tasked with the responsibility to pass along our stories to future generations, how might we broaden our understanding so that we may give future generations the gift of a more complete picture?

Women’s History Month is a reminder to probe deeper, an incentive not to take anyone’s account of history at face value. March might be coming to an end, but we can let it launch us into a year-round adventure of discovery.

Shabbat shalom,

Lizzie Berne Degear

Reclaiming Hidden Voices

by Rabbi Misha

"In all the travels of the Israelites, whenever the cloud lifted from above the tabernacle, they would set out; but if the cloud did not lift, they did not set out—until the day it lifted. So the cloud of the Lord was over the tabernacle by day, and fire was in the cloud by night, in the sight of all the Israelites during all their travels."

Dear friends,

"In all the travels of the Israelites, whenever the cloud lifted from above the tabernacle, they would set out; but if the cloud did not lift, they did not set out—until the day it lifted. So the cloud of the Lord was over the tabernacle by day, and fire was in the cloud by night, in the sight of all the Israelites during all their travels."

Thus ends the Book of Exodus, with words that seem relevant to me this week since we moved out of our place a couple days ago. At Torah Byte yesterday we calculated approximately how many Israelites there were in the desert, and got to something like 2,000,000 including children. Moving a group that big seems even harder than moving a family in Brooklyn. Which is to say that this won't be the longest or deepest letter I've ever written. But I did want to highlight some historical women who showed up in my studies and thoughts this week, it being Women's History Month.

One of the great prophets who foresaw a massive move of the nation from Israel to Babylon was a woman named Chuldah. Today, she doesn't have the same name recognition as her contemporary Jeremaiah, but he knew she was the greatest prophet around during the early days of his prophecy when she was still alive. When Josiah, king of Judea asked her whether his religious reforms will save the nation from being exiled she flatly says no. It's too late. That great forced move is upon us. Josiah looks for another prophet who will provide a better answer, but the tone of Jeremaiah's prophecy changed from hope to doom. He knew that out of everyone, she's the most connected to the truth. A few decades later her prophecy came true.

This week's parashah also mentions some women, though not by name. They are women of wise hearts (חכמת לב) who volunteer their skills to build the tabernacle, that moving holy space we kept in the desert. Last Shavuot, Dr. Lizzie Berne Degear taught us about the women's weaver guilds of ancient times, who it seems have penned some important biblical passages. The wise-hearted women in this week's parashah are described as weavers and sowers who volunteer in great numbers, without whom it seems the tabernacle could not have been constructed.

Next week I'm excited for you all to read some of Lizzie's words about her scholarly work. Perhaps the main focus of Lizzie's work is the reclaiming of women's voices from ancient times. She shines a light on the tremendous influence wise-hearted women had on our tradition, and the ways in which these voices were buried by the patriarchy. She can help us migrate away from the male-dominated view of our tradition.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Polyamory, Poligamy and other Forms of Insanity

by Rabbi Misha

Whenever I hear stories from my polyamorist friends I feel a combination of admiration, jealousy and gratitude.

Students, parents and teachers at the Garden of Stones of the Museum of Jewish Heritage yesterday.

Dear friends,

Whenever I hear stories from my polyamorist friends I feel a combination of admiration, jealousy and gratitude. I find myself admiring their ability to overcome norms we’ve been fed for so long, and step outside of the gloriously, completely insane project of monogamy. I find myself jealous of their freedom, of the explorations they are conducting, both physically and emotionally. And I find myself grateful for the path I’ve chosen, and its innumerable gifts. From the safety of my rich monogamy I ask myself: could I do that?

This week’s parashah is not about polygamy. It’s about two lovers who are obsessed with one another. It’s about cheating, jealousy, rage and commitment. It’s about what happens when a desperate lover feels abandoned and strays toward another.

“Set me as a seal upon thy heart,” they say to one another, “As a seal upon thine arm; For love is strong as death, Jealousy is cruel as the grave; Its flashes are sparks of fire, the burning flame of Yah.”

This is the fiery love affair still going on between the people of Israel and our God. This week’s Parashah describes one of the most tumultuous moments in this relationship, the sin of the Golden Calf, where the people love another form of divinity.

“When the people saw that Moses was so long in coming down from the mountain, the people gathered against Aaron and said to him, “Come, make us a god who shall go before us, for that fellow Moses—the man who brought us from the land of Egypt—we do not know what has happened to him.”

Yesterday, walking around the Museum of Jewish Heritage with 30 students and parents, I found myself wondering about this love affair between Israel and God. These eleven and twelve year old kids looked at objects of Jewish life in Europe before the war. A ketubah, an etrog holder, a grand Sukkah painting; The physicalization of this age-old love story. Then they saw evidence of a thousand years of persecution, Nazi stereotypes of Jews, photos from Germany, Poland, Ukraine. They passed by a Torah scroll saved from a synagogue on Kristallnacht, a photo of Jews making matzah in the ghetto, a pair of tefillin that a survivor of Sobibor said kept him alive. Even through that darkest of nights, the love affair continued, for some.

Most of us, however, who live in the shadow of the Holocaust, live with a very serious abandonment syndrome. Our lover stranded us, and now we walk alone, with only one other to love. Is it a wonder, therefore, that we live in this age of Golden Calves? “Calves everywhere,” my brother described it to me on the phone this morning.

And yet, despite my brain, my heart stubbornly loves. A sickness I long to feel, and when I do I know all is as it should be, even as I have no idea where I might find my beloved.

"Daughters of Jerusalem, I charge you— if you find my beloved, what will you tell him? Tell him I am sick with love."

Some people can have multiple lovers at the same time. This Misha who’s writing these words has loved Lord Siva and Ganesh, Jesus, Allah, the sun and the moon, and countless other divinities. Nowadays he bows down before this one intense and crazy lover, the God – or lack thereof – of Israel.

PS

Many of you have asked me for the recording of the conversation about what's going on in Israel we held on Tuesday. It is available, so feel free reach out and I will share the link.

For those of you asking how you can help:

This Sunday at noon at Washington Square Park there will be a protest demanding a democratic Israel. Bring flags and signs or just show up. In addition, The New Israel Fund has created an emergency fund raiser, to which you can get more information and donate HERE.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Beautiful Demons

by Rabbi Misha

Purim conjures the best and worst memories. Ridiculous feasts, family gatherings, insane Jerusalem karaoke parties, drunken laughter, silly costume duos with friends, moments of the deepest honesty and most liberated dancing.

Dear friends,

Purim conjures the best and worst memories. Ridiculous feasts, family gatherings, insane Jerusalem karaoke parties, drunken laughter, silly costume duos with friends, moments of the deepest honesty and most liberated dancing. And also times when that loosening unraveled horror, bad drunken behavior, nastiness, parties gone wrong, and most prominently February 25th, 1994 when Baruch Goldstein, Yimakh Shmo (may his name be blotted out) murdered dozens of Muslim worshippers in the Tomb of the Patriarchs in Hebron.

This year I’m feeling both extremities, and we’re going to try to go in both directions at once at the Shul. Sunday we will party in person, and Tuesday night we will Zoom through what’s happening in Israel/Palestine.

As Purim of 5783 approaches, I find myself oscillating between the improvisational ease of the jester and the deep sadness of the prophets. My homeland, where I grew up and where my parents, brothers, sisters-in-law, nieces and nephews and many of my best friends live, has morally and structurally collapsed. At the same time it has also woken up, stood on its feet, risen into collective song. I read the news and scratch my eyes: the Jews have performed a full-fledged pogrom. The Israeli Minister of Defense says the Palestinian village that was attacked should be “wiped out by the state.”

Hundreds of Jews, including my father went to that village today to show solidarity. Their buses were stopped by the army, forbidden to show empathy. So they walked instead. Tear gas followed, people beaten. My father made it through and sent pictures of a serene mountain village. My friend, Avital’s father didn’t fare as well. Her father, Avraham Burg, is the former Chairman of the Knesset and director of the Jewish Agency. This is the person who used to be the lead representative of Zionism in the world – today there were videos of him pushed to the ground by Israeli policemen, preventing him from reaching Hawara.

It’s hard for me to think of anything more upside down than that.

And then there are the incredible protests that everyone I know there has been a part of. This Wednesday the country was shut down by Israelis who know that if this isn’t stopped the country as we understand it is finished. Streets blocked all over the country, protests in front of elected officials homes, an array of hopeful, forward looking activity, the likes of which I have never seen in Israel or the US. It’s a celebration of political expression, imperfect though it may be.

So the upside down is itself upside down. Mirrors and masks and costumes galore.

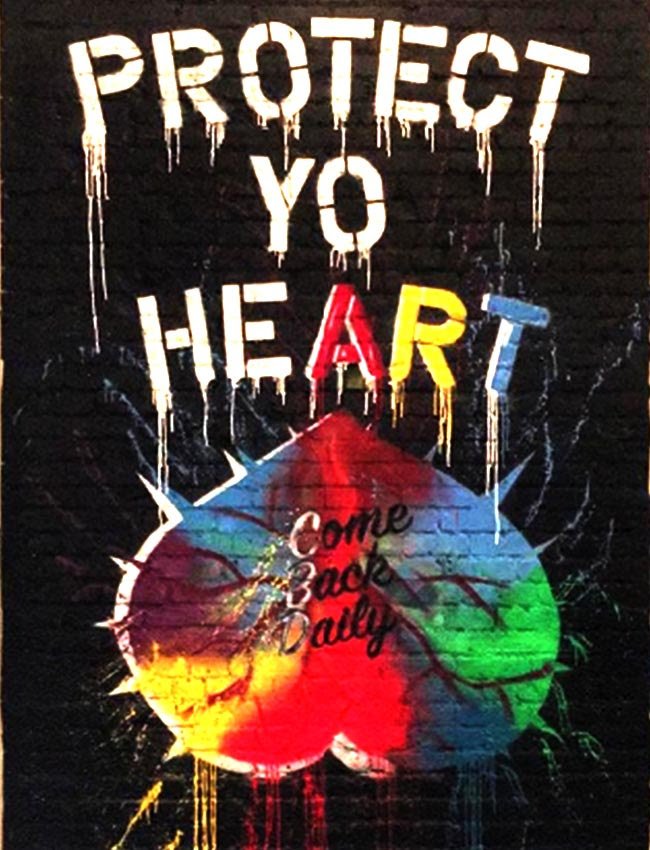

Our job seems to be to celebrate the groundless upside earth we stand on, and that’s what we will do this Sunday. The artist Uncutt will paint dancer Dorian Cervantes after leading us through his exhibit of Protect Yo Heart – art based on the verse from Proverbs. Fabio Tavares will unravel himself in movement. Wine and food and DJ and music and VR goggles and ancient stories and a rejoicing over this fragile insanity we live.

And then our upside-down job is to understand what’s going on so we can stand with sanity. Tuesday evening Rabbi Amichai and me will try and give you our perspective, answer and ask questions, and help us all find some solid ground on which to stand together on our heads.

Purim is there to release our demons. Let’s make sure they are beautiful demons of liberation, not ugly demons of destruction.

Hope to see you at both events!

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Misha

The Activating Heart

by Rabbi Misha

One of my teachers toward ordination was a Hasidic drummer who went by Reb Dovid. Studying Talmud with him, which I was lucky enough to do weekly for seven good years, was a careful text study of ideas in the form of a whirlwind of thought.

by Itamar Dotan Katz

Dear friends,

One of my teachers toward ordination was a Hasidic drummer who went by Reb Dovid. Studying Talmud with him, which I was lucky enough to do weekly for seven good years, was a careful text study of ideas in the form of a whirlwind of thought. R’ Dovid also knows about money. Most people don’t know him as a drummer but as the director of an energy consultancy company. And he knows about spirit. At least as many people know him as an avid student, who spends hours every day at the House of Study. One of the simplest and greatest lessons he taught me was this: money does not belong to us. We feel generous when we give tsedakah. In truth we are just passing along what we were holding onto as custodians.

Rabbi Dovid’s notion can free us to transform our most physical, mundane and dangerous property, with which many of us have weird, screwed up relationships, into goodness, love and purpose. Money can ruin us, or it can elevate us.

This week’s Parashah is called Trumah, Hebrew for donation. When we come to build the tabernacle, the abode of God in our midst, we first take a Trumah from “every person whose heart so moves them.” Out of the thing that is entirely utilitarian we build the most ephemeral, the most useless, the most ridiculous – to imagine that God needs an abode is absurd, especially for theists! - place we have; and thus the most important.

Trumah is the Bar Mitzvah parashah of my nephew Nahar. I’ve probably mentioned him before, because he’s this incredible person who teaches those around him how to be present and find joy. He’s also in a wheelchair and severely disabled since a car crash when he was an infant. Nahar’s was a Bar Mitzvah for the ages. I remember him up by the Torah, hitting the button that would play the recording of the Torah blessing: “Barchu et Adonai Hamvorach!” I remember all of us replying, “Baruch Adonai Hamvorach le’olam va’ed,” and then waiting as he found a way to bring his hand to the button again to complete the blessing. And I remember the deep connection that emerged that day between Nahar and the words: איש אשר ידבנו לבו, “every person whose heart so moves them.”

Trumah means donation or gift, but it comes from the root “to raise.” A donation has the power to raise the dirt to the heavens, to raise selfishness to giving, to raise depression to quiet joy. Every person whose heart so moves them can take part in the raising up of spirit. You can look at Nahar today and see a nineteen-year-old who can’t speak or move freely, or you can experience his great soul, if you allow your heart to move you into a space of generosity.

It is through this generosity that the things we value most are created. This Shul was created by such an energy by Holly and Ellen and many others, and maintained through the love, work and donations of countless others over the years. The same is true for our arts institutions, our justice workers, and most other organizations of value in our society.

This Shabbat I invite you to make a donation. Elevate your money. Or rather, pass on the money that landed in your hands. I’ll name a few organizations and initiatives that seem especially important right now. Choose one or more or all of them, or give to one of your own causes.

This little Shul that could, The New Shul is, as per, on the brink. No joke. Help us HERE!

VOCAL NY is on the front lines of the valiant and perpetual fight against homelessness and poverty in this city.

The Freedom Agenda is working to close the stain on this city known as Rikers Island.

Torat Tzedek : The Torah of Justice is leading the precarious charge for a Judaism in Israel/Palestine that is based on the inherent value of every human life.

HIAS has been the leading American organization working for refugees for over a century and is needed now more than ever.

The Multifaith Alliance for Syrian Refugees is hard at work supporting those who have lost their homes in the recent devastating earthquake.

Jews for Racial and Economic Justice is a local org that partners with other communities on issues such as fair pay for home-care workers, police accountability and combating hate.

One example of their work is taking place tomorrow night, where in response to the white supremacists Day of Hate, JFREJ is leading a Havdalah Against Hate, which we can all easily join from wherever we are.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Misha

LUGGAGE WITH LOVE

From UJA: Ukraine Response

LUGGAGE WITH LOVE

GCS Amirta Pendharkar alerted us to Luggage with Love, a drive to collect clean, zippered luggage and suitcases for people who have to move suddenly and don't have luggage, such as kids entering foster care, and people who have experienced domestic abuse. It will be a mitzvah project for Rose. Those interested will bring stuff to our house by 2/23 and we will deliver to the charity.

Please forward, and if you can donate, text Nina Kaufelt at 646-285-8541.

Beyond the Flags

by Rabbi Misha

Before I left my house last Sunday to participate in the weekly demonstration against the legal overhaul that would demolish the separation of powers in Israel, I debated what symbol or slogan to bring.

by Gili Getz

Dear friends,

Before I left my house last Sunday to participate in the weekly demonstration against the legal overhaul that would demolish the separation of powers in Israel, I debated what symbol or slogan to bring. Israel’s outwardly racist Minister of National Security had recently begun to enforce an old ban on Palestinian flags, so perhaps that’s the thing to wear. After all, the Palestinians are the ones who would suffer most if this overhaul took place. On the other hand, there are those who claim that this is an internal Israeli issue, removed from the larger conflict, and the way to beat this law is with Israeli flags. Indeed the protests in Israel have been a sea of blue and white flags. Maybe a joint flag is the right move, I pondered? Or maybe all this flag business is nonsense. I printed out a slogan in Hebrew from demonstrations past: “Jews and Arabs refuse to be enemies,” taped it to my jacket and headed out.

When I arrived at Washington Square Park, I learned that one of the other speakers, an Israeli American named Udi Aloni, didn’t feel comfortable speaking since there were only Israeli flags. A few minutes later, however someone showed up with two flags, one Palestinian and the other half Israeli half Palestinian. She gave Udi the Palestinian one and he came into the fold. As soon as he came near the other few hundred folks assembled an argument ensued. Several loud voices demanded that Udi remove the flag. “This isn’t what this protest is about,” they said. “It’s about democracy,” he roared, “From the river to the sea all the people must be free!” “This isn’t the time for that,” they answered.

Palestinian flags have been an issue at the demonstrations in Israel too. The first few weeks, in classic fashion, the left couldn’t agree, so there were two separate demos in Tel Aviv. Since, they have found a way to bring everyone together, so long as those with Palestinian flags stay in a corner off to the side. Here in New York, the demonstration kept coming back to this bitter argument.

When it came my turn to speak, I described my worry that if this overhaul passes, my nieces and nephews will have no future there, that my father would be arrested for his peace activism and the courts would be powerless to help him.

I then spoke about the opportunity this moment offers for the country to change course. The first ever event of “the faithful left,” Jews whose God speaks to them not of land but of the value of every human life, drew 700 people in Jerusalem last week. Maybe even the association between right wing policy and being a religious Jew could be challenged.

There is hope in this moment: Imagine half of the US going on strike and instead of going to work showing up in Washington to demonstrate. This coming Monday will be the second in a row in which something like that takes place there. It is a hopeful “Kumah” moment, in which the people are rising up. My friends there describe a marvelous scene in which Israelis of all types are protesting, including some settlers, ultra-orthodox Jews, Mizrahi, Ashkenazi, gay, straight, old and young.

But one population is notably absent. It’s hard to ignore the tribal tone of these calls for democracy. A Palestinian citizen of Israel was beaten up last week during the demonstration in Tel Aviv because he was calling for an end to the occupation. Even in New York the mere sight of the Palestinian flag threw people into a rage. Events like these turn my positive feelings to what my father called “dark hope.”

From my vantage point, this moment offers an opportunity to join Jews and Arabs together for democracy. Otherwise, the country will not only continue to rule over half of the population there without giving them basic rights – as the Israeli courts have allowed mind you - but it will also remain on track to become a restrictive theocracy for all. The coalition agreement between Netanyahu and the ultra-orthodox Shas includes a clause to give the religious courts - where women are not allowed to be judges, and often prevented from speaking - equal power to the civic courts. Preventing this government's legal overhaul from happening is crucial to creating a sustainable future.

Before I closed my remarks, I pulled out my grandmother, Dina z”l’s book and showed it to the crowd. The year before she passed, she was reading the prophets. I quoted the prophet Amos’s words, suggesting two paths available to the Israelites of old. One leads to exile – “Israel will surely be exiled from its land” - and the other to a peaceful joy:

“They shall rebuild ruined cities and inhabit them;

They shall plant vineyards and drink their wine;

They shall till gardens and eat their fruits.”

But perhaps it’s the final verse that my Savta ever quoted me that is most relevant:

לֹא־נָבִ֣יא אָנֹ֔כִי וְלֹ֥א בֶן־נָבִ֖יא אָנֹ֑כִי כִּי־בוֹקֵ֥ר אָנֹ֖כִי וּבוֹלֵ֥ס שִׁקְמִֽים׃

“I’m no prophet, nor the child of a prophet. I’m just a shepherd who grows figs.”

Don’t label me with titles, says Amos, or weigh me down with your flags. Any visions I may share, grow out of nothing but my simple human life.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Transcending the Physical

by Rabbi Misha

Rabbi David of Lelov was frustrated. He had devoted his life to matters of spirit. He ignored the talk of the town, the news and gossip, and instead focused on eternal matters.

by Cindy Ruskin

Dear friends,

“Rabbi David of Lelov was frustrated. He had devoted his life to matters of spirit. He ignored the talk of the town, the news and gossip, and instead focused on eternal matters. He followed the laws of his ancestors, prayed, did acts of loving kindness and charity, studied and taught. And yet, he was still stuck in the physical realm, thinking about his needs, his pains, his desires, his worldly aspirations. He couldn’t transcend this body of his no matter how hard he tried.

He looked to the Prophets of old and found that many of them lived with little food or drink, not to mention sex. Following the advice of a mystic several hundred years before his time, Rabbi David decided he would deprive his body until it left him to unite with his spirit. For six years he fasted all week long, eating only on Shabbat.

When the six years had been completed, and the seventh was upon him, he awaited the spirit’s appearance. “Now,” he thought, “God will be with me.” But no such experience took place. Dispirited, he committed himself to another six years of fasting between Sabbaths. After twelve years of fasting, however, no transcendence emerged. The rabbi still thought about food and sex, he still felt jealousy and resentment, still sought the approval of others, was still consumed with desires. God had not appeared to him as he had thought. “Surely,” he thought, “I must be very close. But some invisible door is blocking me from entering to see the Queen.”

The rabbi knew who would be able to show him that door and unlock it. So, he travelled all week to the village where his old friend, Rabbi Elimelech lived and taught. He arrived on the eve of Shabbat, and entered the small synagogue, which was already filled with beautiful singing. When the prayers had been completed, the song turned to warm smiles and a sweet sense emerged of a community that had entered together into a new mental space. Rabbi Elimelech, with his son by his side, approached each person and greeted them warmly, with embraces and warm words. Everyone, that is, except for Rabbi David, whom he passed by without a word.

R’ David was distraught. He was offended, humiliated, deeply hurt. Sitting in his room at the inn late that night he calmed himself down. “Many years have passed. I look different, so much thinner than I was, and grayer and older. He must not have recognized me. I will return tomorrow for the morning prayers.”

The next morning again the prayers rose high, and the people lifted one another toward the heavens with their singing. But when the post-prayers Kiddush was completed, and all had drunk some wine to warm their souls, again Rabbi Elimelech greeted each person – except for Rabbi David.

This time R’ David was angry. His mind raced with fury. “How could he do this to ME?!” He packed his small bag so that he could leave as soon as Shabbat ended and planned not to return to the little shul ever again. But as the evening approached R’ David found his legs pulling him toward the Shul. He knew that R’ Elimelech always speaks words of wisdom during the final meal of the Sabbath before the holy day ends, and he couldn’t get over his draw to hear what he would say. So he placed himself outside of the shul by the open window. The assembled community drank their vodka and savored their pickled herring and other delights as they shared stories and sang nigguns. At last R’ David heard the voice of his old friend.

“You know,” opened Rabbi Elimelech, “People come to me with a gaunt and sad body, after having fasted and tormented themselves for twelve years. They believe they have done penance, removed the barriers between themselves and God. After that they believe themselves worthy of the spirit of holiness, and they come to me to help them through the threshold. They are ready to walk through the door and come in front of the queen, and just need me to show them where this door is.”

The rabbi paused, took one more sip of his vodka, and continued.

“But the truth is that all their discipline and all their suffering is less than a drop in the sea: all that work they’ve done does not rise to God, but to the idol of their pride. Such people must turn away from everything they have been doing, and begin to serve God from the bottom up with a truthful heart, a full belly and a song on their lips.”

These words cut R’ David to the heart. His breathing stopped, his legs failed, and he reached his hands to the wall so he wouldn’t fall over. When his breath returned, he felt his body tremble and tears burst out of his eyes like a river.

When the Havdalah prayers were concluded, R’ David opened the synagogue door in great fear and waited on the threshold without entering. Rabbi Elimelech rose from his chair, ran over to R’ David and embraced him. “Blessed is the one that comes,” he cried out. He helped the broken rabbi to the table and sat down by his side. At this the rabbi’s son couldn’t contain his amazement: “Father,” he said, “This is the man you turned away twice because you could not endure the mere sight of him!”

“Not at all,” replied the rabbi. “That was an entirely different person! Don’t you see that this is our dear Rabbi David?”

This Hasidic story was adapted from The Penitent in Martin Buber's Tales of the Hasidim.

This Sunday I invite you to join me at noon at Washington Square Park for the demonstration against the Israeli government's terrifying plan to gut the court system, where I've been asked to share some words.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Kafka on Faith

by Rabbi Misha

“A man cannot live without a steady faith in something indestructible within him, though both the faith and the indestructible thing may remain permanently concealed from him. One of the forms of this concealment is the belief in a personal god.”

Dear friends,

“A man cannot live without a steady faith in something indestructible within him, though both the faith and the indestructible thing may remain permanently concealed from him. One of the forms of this concealment is the belief in a personal god.”

Kafka’s great aphorism deserves our attention. Let’s examine part I:

“A man cannot live without a steady faith in something indestructible within him”

Yesterday I asked three twelve-year-olds what their take on God was. Within seconds the conversation turned to the afterlife. “I can’t imagine everything just ending, turning black,” Arthur said.

It seems to me that Kafka is making a psychological observation. Human beings live with the constancy of their ever-present selves. We are incapable of imagining our self - whatever that may be or not be - not being. So long as we are alive, we believe we will always live.

אם אני כאן הכל כאן, said Hillel in the Talmud: “If I am here than everything is here.” ואם איני כאן אז מה כאן, he continues: “and if I’m not here, than what is here?”

Even in our most broken moments, when we see nothing in ourselves that is strong and enduring, we cannot shake the notion that we are a part of what is. We imagine being dead and look for some other stage or state of being. Which isn’t to say we all believe in the afterlife in our logical brains.

Part II: “though both the faith and the indestructible thing may remain permanently concealed from him.”

Let’s first look at "the faith," and then at "the indestructible thing" itself.

Would we all say that we believe there is something indestructible in us? That we will, in some fashion, continue to exist forever? Certainly not. Even those who do believe in a neshamah, or soul that transcends our physical existence, have their moments of doubt. We are all in some sense agnostics on this question, even if we claim to be believers or non-believers. This is the concealment that Kafka is revealing. We have all witnessed death, if not of human beings than of animals, bugs, plants. We know that life ends. So we go around thinking that we know we will end. But the Kafkaesque fact is that we believe we won’t. We have, according to Kafka, a type of Emunah Shlema, complete faith, in the existence of the eternal in us.

Now let’s look at this “indestructible thing.” There are certain things that cannot be taken from any human being. The Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish wrote:

"It is possible for prison walls

To disappear,

For the cell to become a distant land

Without frontiers."

Darwish is describing the imagination. Freedom of the mind, a person’s way of thinking, cannot be taken away. Something about us is indestructible, is it not? Maimonides calls it the Tzelem Elohim, the image of God, our non-physical aspects, primarily our mind. Do we view it as indestructible? Not always. We walk around unaware of or underplaying our uniqueness and brilliance most of the time.

“Both the faith and the indestructible thing may remain permanently concealed” from us.

Part III: “One of the forms of this concealment is the belief in a personal god.”

Maimonides laid what all 613 commandments in the Torah are. The Talmud taught that’s the number of commandments, but no one had ever defined which exactly they were because there are so many different ways to understand every line in the Torah. As soon as he begins, with what Maimonides calls the first commandment, there’s massive controversy:

The commandment to believe in divinity. And that is that we believe that there is an Origin and Cause, that He is the power of all that exists. And [the source of the command] is His saying (Exodus 20:2), "I am the Lord your God."

Not only does his biblical source: “I am the Lord your God,” not sound like a commandment, but to command anyone to believe in anything seems silly. Many wiser and more learned than me have written about it, so all I’ll say in our context is that perhaps what we are being commanded, if indeed we are commanded to do this, is to bring to mind that inescapable faith in the indestructible within, which we so easily live without in our conscious minds. In other words, this commandment seems the most impossible – to believe in some permanent truth – but it’s actually impossible not to follow, because it’s built into our humanness. Our job is to keep pulling it out of hiding.

What’s tricky for me in Kafka’s phrase is the word “personal.” I’m not clear what exactly a personal God is, or what Kafka meant by it. One could certainly read Maimonides’ words as having nothing to do with a personal God. He speaks of “origin and cause” and of a “power of all that exists.” It’s the biblical quote that complicates this, when it uses the phrase “your God.” Now it sounds personal, even if it was used in the plural, God speaking to all the Hebrews.

For Kafka, the notion of a personal God is one of the ways in which we conceal the faith we have in the indestructible in us. We think we are working on faith, when in fact we are concealing it further. We relinquish our indestructible and put it in the hands of God. We await salvation. We disempower ourselves by removing the indestructible from inside us to outside. Maimonides did believe strongly in separating the self from God. He thought we are commanded to believe that this origin, cause and power exist “שם,” over there. My instinct is different. In my translation of Psalm 30 I rendered the phrase “Adonai Elohay,” normally translated “Lord my God” like this:

“You

Who are my self and all at once”

Tomorrow night I hope you can meet me for cocktails and some Zohar at Cowgirl, a bar on Hudson Street from 6-8pm. We’ll mark Tu Bishvat, the New Year for the Trees. Perhaps the trees can teach us about this question of faith: the indestructible and ever-lasting in the trees, which dies and is born, is both a part of the earth and a unique entity that keeps the world in balance.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Our Whispering Past

by Rabbi Misha

“This is what human beings can do,” it whispers. “Be scared.” “Be brave.” “Be grateful.” “Be Jewish.” “Take words seriously.” “Care.” “Act.” “Remember.” Different whispers at different moments, different commands to different people.

Protesting to close Rikers Island Jail yesterday

Dear friends,

* The promised note with words from Dr Lizzie Berne Degear had to be pushed back, and will be coming soon. Instead I offer some reflections on the past week:

Seventy-eight years ago today Auschwitz was liberated. What does it do, Auschwitz? Mostly it sits there in our consciousness, an elemental energy pulsating outward. “This is what human beings can do,” it whispers. “Be scared.” “Be brave.” “Be grateful.” “Be Jewish.” “Take words seriously.” “Care.” “Act.” “Remember.” Different whispers at different moments, different commands to different people.

Here are a couple whispers that I’ve been hearing this week.

This evening we will get the video of Tyre Nichols getting beaten to death by police officers in Memphis. We will put it in the category of African American lives taken lightly by police.

In Palestine we reached 29 people killed this year. Every day this month at least one life taken by Israeli soldiers or police. Five kids. A 60-year-old woman. Men in their prime. Some involved in violent resistance, others not. Lives cut short.

In New York City the mayor gave his State of the City address yesterday as a large group of protesters demanded he hold to his campaign promise and shut down Rikers Island. Maia and I stood holding a banner with the names of two of the 19 people who died in custody there last year. We heard family members of the deceased describe their loved ones. Most of them described people with mental illness, and indeed around fifty percent of the jail population there suffer from mental conditions.

It is a known fact that the Nazis first exterminated people with mental conditions and other “undesirables.” The first people to be murdered in in the earliest gas chamber facility, Brandenburg An Der Havel, were mentally ill prisoners. We are, thank God in a completely different situation than 1940 Germany. But since visiting Brandenburg An Der Havel I carry the understanding that what led to Auschwitz was the false distinguishing between people with value and people with no value. These people matter. These don’t.

So, when we were chanting “Treatment not Jail” yesterday, I could hear whispers from our past. And when we heard a bereaved mother describe the violence in their neighborhood when her son was growing up, the racialized segregation in our city came into focus, and with it more whispers from our past.

They all matter. Those killed by police like Tyre Nichols, those killed by the IDF like Magda Obaid, those who died by neglect in Rikers as they await trial like Mary Yehudah. Each of the approximately 1.1 million people murdered at Auschwitz.

There is something incredible that happens at protests sometimes, when you find yourself speaking words out loud. When we chanted “Treatment not jails,” over and over yesterday, the truth of it all, the pain and suffering it implies, the justice behind that simple demand all flooded my consciousness. Those whispers I was hearing were allowed out in the hopeful act of speaking truth with my fellow city-dwellers.

I remember a protest in Red Hook about ten years ago, before “All Lives Matter” became the anti-BLM slogan. My family and I were some of the only white people marching. At one point in the protest, the chant led by the mostly Black residents of the local NYCHA housing units turned from “Black Lives Matter” to “All Lives Matter.” I was amazed at the generosity of spirit displayed by this underserved, historically oppressed community. And I was further amazed at the feeling that accompanied speaking these words out loud with others. All lives, every single one, matters. There’s no doubt that what we need to be chanting in the US is Black Lives Matter. But it’s too bad that ALM was co-opted by those standing in the way of equality. What a hopeful, prayerful statement it is – every single one of our lives – yours, mine and that of every person - matters.

May that be the lesson of our whispering past.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Misha

She Torah

by Rabbi Misha

"I’d like to speak the blessings in the feminine,” Ella told me. “What would that be in Hebrew?”

Hayley Antonelli

Dear friends,

(*There's a little invitation to a protest I don't want you to miss at the bottom.)

"I’d like to speak the blessings in the feminine,” Ella told me. “What would that be in Hebrew?”

It would start “Barchu et Adonai Hamvorechet.”

“And then?”

“Bruchah Adonai Hamvorechet le’olam va’ed!”

At her ceremony, for the blessings that officially made her a Bat Mitzvah, Ella flipped the gender of God. It took a young woman from a family of four women to soften the male-dominated idea of God for all of us in the room and suggest a Jewish Goddess instead.

This is not a new idea of course. In the Amidah we find the phrase “מודים אנחנו לך”, We thank You, in the feminine. There are many such examples in the prayers. Yah, as in Helleluyah is considered the feminine presence of God. In one of the central Kabbalistic depictions of divinity we find a trifecta of Gods, among them the Nukba, or female Goddess who plays a central role in the divine structure of things.

But overwhelmingly God is referred to grammatically as male, and that is the beginning of patriarchal thinking. How we speak is how we think is how we behave. There’s an obvious link from the male God to the death of Mahsa Amini and the oppression of women worldwide.

Since Ella’s Bat Mitzvah I began addressing God in the feminine in some of my prayers. The result has been a widening and welcoming of the idea of God. I continue to keep many of the prayers in the traditional male form, since beneath these notions of gender is a wider understanding of the genderlessness of God. God is the place of no separation, beyond definition, transcending ideas, identities, anything human thinking can produce.

That’s why many of us try in English at least to avoid gendering God altogether. Sometimes the pronoun “they” fits. More often no pronoun is better. But we have to use language unfortunately.

These last few months, a group of us has been gathering on Zoom to learn from our scholar-in-residence, Dr. Lizzie Berne Degear. Lizzie has been connecting us in powerful ways to the feminine in our tradition, and to the female roots of our tradition that have been buried under the male-dominated face of the last two millennia. She is opening our minds not only to female divinity, but also to pieces of the Jewish bible that could have been written by women. She has invited us to experience an ancient reality of women teachers, with a sweet and beautiful and inviting Torah on their lips.

Imagine a Torah written by women. Imagine Jewish law written by women. Imagine how that affects your connection to Judaism.

In next week’s letter you will hear from Dr. Lizzie in her own words about her work.

This week’s Parasha opens with a multi-gendered mesh of divinity:

“And Elohim spoke unto Moses, and said to him, I am YHVH; And I appeared unto Avraham, unto Yitzchak, and unto Ya’akov, as El Shaddai, but by my name YHVH I did not make Myself known to them.”

Of the three versions of divinity in these verses none are overtly gendered. Elohim is plural, grammatically meaning “gods.” YHVH is an unpronounceable mis conjugation of the verb “to be.” “El Shaddai” includes both male and female connotations, the word “El” denoting a male god, and “Shaddai” literally meaning “my breasts,” and harkening back to pre-Jewish Middle Eastern goddesses.

We have a lot of undoing to get through on route to this liberated divine fluidity that will allow all of us to be ourselves.

Before I sign off, I’d like to invite you all this coming Thursday to join our BLM chevrutah and protest the city’s inability to protect the human rights of the incarcerated, and to demand action to close the stain on this city that is Rikers Island Jail, where 19 people were killed last year in custody. Details HERE. Email Maia if you can make it, she's coordinating our group.

If you like, try this blessing in the feminine when you light the candles this evening: