Sort by Category

MUSIC: Know from where you come - Da me'ain bata

Original niggun and trumpet by Frank London

Original niggun and trumpet: Frank London

Vocals: Jack Klebano

Vocals and guitar: Yonatan Gutfeld

Violin: Marandi Hostatter

Percussions: Aaron Alexsander

דע מאין באת, ולאן אתה הולך, ולפני מי אתה עתיד לתן דין וחשבון. מאין באת, מטפה סרוחה, ולאן אתה הולך, למקום עפר רמה ותולעה. ולפני מי אתה עתיד לתן דין וחשבון, לפני מלך מלכי המלכים הקדוש ברוך הוא:

Know from where you come, and where you are going, and before whom you are destined to give an account and reckoning. From where do you come? From a putrid drop. Where are you going? To a place of dust, of worm and of maggot. Before whom you are destined to give an account and reckoning? Before the King of the kings of kings, the Holy One, blessed be he.

Translating Forward

by Rabbi Misha

I wake up from an intense dream. I go over its details in my mind. I’m full of the ramifications of this dream: psychological, emotional, spiritual. I turn to a loved one or friend and begin describing it. Their attention fades quickly.

Dear friends,

I wake up from an intense dream. I go over its details in my mind. I’m full of the ramifications of this dream: psychological, emotional, spiritual. I turn to a loved one or friend and begin describing it. Their attention fades quickly. They humor me by listening to the end and summarize it in a word: “Anxiety.” Or “Fear.” Or “Weird.” I am left alone with the emotions I was entirely unable to translate.

Writer and translator Jhumpa Lahiri writes in her most recent book about “the supremely disorienting act of translating myself.” She means writing something in one language and then translating it into another. But the act of translating ourselves is one that we engage in daily. With each person we speak differently, so that they will be able to hear us. So that we will feel understood. Or sometimes we give up and keep our inner world to ourselves.

King David, the 10th century BCE Hebrew poet was good at translating his inner world into song. His poems, which we call Psalms are expressions of his most intimate and vulnerable thoughts. He speaks them to his God, and through his relationship to that God, human beings ever since have deepened their relationships to their own God. It didn’t matter that the vast majority of them did not speak the same language as David. Nor did it matter that they practiced a different religion altogether. This might tell us something about the place where different faiths, cultures and philosophies meet. His poems have been read consistently by a large portion of humanity ever since they were written.

Many of us, however, have trouble connecting to these poems nowadays. Something isn’t coming through. The fact that the poems are addressed to God makes it difficult for many of us who don’t believe in God, or don’t relate to the way the bible describes God to connect to them. The world is so different now than it was then, we think to ourselves, what does any of this have to do with me?

And then there’s the killer: the translations.

Have mercy upon me, O God,

as befits Your faithfulness;

in keeping with Your abundant compassion,

blot out my transgressions.

We look at the words and feel nothing, or maybe we feel tired. We see nothing alive. We remember the boredom of our religious school education. We rebel against the patriarchy, against punitive authority and disempowering institutions, against the death of spirit, and stop reading. David’s relationship with what he called “El Khai,” “a living God” is not even a memory. It’s forgotten, or worse, mocked.

I am lucky on that front. First of all, I speak Hebrew, and can read him in the original. I also was given tools from an early age that help study a biblical text, such as where to find commentary, how to mine biblical Hebrew and how to imagine my way into a biblical poem. Armed with those tools I spent seven years studying the entire Book of Psalms. What I found was the open heart of an extraordinarily communicative poetic giant, that expressed my fears, discontents, ideas and dreams in ways I could never do myself. Through the act of study, I managed to translate antiquated Hebrew into something valuable to me.

I still, however, felt alone with the poetry. I couldn’t communicate what I experienced in them to anyone but my study partners, with whom I was mining the texts. I felt a strong to desire to try to communicate them to others. And so I began working on translating a number of Psalms into an English I hoped would manage to cut through both the linguistic and the philosophical barriers between 21st century New Yorkers and the Psalms.

You remember that line up above? Have mercy on me etc.? Read it one more time and then see what I did with it in my translation of Psalm 51:

Treat me kindly, Lover

Lay my head on your breast

Melt my guilt like ice.

Believe it or not, I think that this version – for us today - is much closer to what David meant when three thousand years ago he wrote:

חׇנֵּ֣נִי אֱלֹהִ֣ים כְּחַסְדֶּ֑ךָ כְּרֹ֥ב רַ֝חֲמֶ֗יךָ מְחֵ֣ה פְשָׁעָֽי׃

Of course, it’s different than the original in many ways. But, as Jhumpa Lahiri writes:

“What one writes in any given language typically remains as is, but translation pushes it to become otherwise.” This is what it means when we say we are receiving the Torah. We are translating it forward, taking it on and playing with it in our mouths, hearts and minds.

Tomorrow evening, when we gather to mark what happened at the foot of that mountain all those thousands of years ago, I am excited to have the opportunity to share with you some of these rather interpretive translations. I’m even more excited that the poems will be read by two wonderful actors, Maria Silverman and Martin Rekhaus, and accompanied musically by Frank London and Yonatan Gutfeld. After the poetry you’re invited to stay for part or all of our Tikkun Leil Shavuot, the traditional all night study session on the night of Shavuot (our version is far less traditional though...). We will be joined by several wonderful teachers, who will deepen our understanding of what it means to listen, to speak and to translate. These include Dr. Lizzie Berne DeGear, Rabbi Jim Ponet, Michael Posnick and Elana Ponet. And if you stay long enough into the night I’m hoping we might even work on studying and translating a psalm together.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Misha

The Bells We Need

by Rabbi Misha

The question is how do we respond to such a devastating week? One answer is: with a bell. (If you have one nearby grab it, it might come in handy.)

Dear friends,

The question is how do we respond to such a devastating week? One answer is: with a bell. (If you have one nearby grab it, it might come in handy.)

A few weeks ago, I spent a couple days on a Zen monastery in the Catskills. Every time a bell sounds there, everything stops. Conversations pause, movement, thoughts, chewing. Instead, people breathe. We can practice that useful, grounding Zen way during the next few minutes.

B e l l

That’s only part of the answer, but if we can do that it can protect us from the spiraling emotions and fears. It can remind us that our lives are right here where we are and not over there, in the headlines. It can remind us to look around and see what is in front of us, to listen to what’s around us and to know that the leaves are still growing on the trees and the cabs are still speeding around the city even if most of them are now called Ubers.

Yesterday I met with a young Trans person thinking about their upcoming B Mitzvah. They were trying to make sense of taking on this ancient tradition whose holy book commands the execution of homosexuals and the harsh punishment of cross dressers. Part of our job as Jews, I told them, is to define which parts of the Torah may have come from a divine source that cuts through time, and which came from a limited human source. This is what it means when we say that we were given the Torah. “But why is it in there,” they ask. Because the Torah represents reality, not just the ideal. So, things like that must be in there. When we accept the Torah we accept reality, we say yes to life with all its faults.

B e l l

The bell, like the Torah is about both acceptance and the fight.

When the Temple was destroyed 2000 years ago our tradition adapted by radically transforming Jewish practice. No more single place of gathering. No more pilgrimage to Jerusalem three times a year. And most importantly, no more animal or harvest sacrifices. Instead of sacrifices came prayers.

In the morning prayers, after the early morning reciting of the verses detailing the sacrificial service in the Temple, we find the following sentence:

“May it be Your will that the speaking of these words be accepted by You as if we offered the daily sacrifice at its proper time, its right place and according to rule.”

I always considered this move the salvation of Judaism, when it turned from the concrete to the abstract, from place to time, from physicality to spirit. It democratized the entire practice, wresting it out of the hands of the priests and into the interpreting bodies and minds of the people. But this week, when I watched Steve Kerr respond to the horrific mass murder in Texas, I saw it differently.

“No more moments of silence,” he said, and I wondered: where is the sacrifice? Where is my sacrifice, the concrete action, the stepping out of my life to solve a problem that keeps getting closer and closer, that could steal the greatest gift I have, my life and the life of those I love? What am I giving up for sanity, for justice, for safety, for community? What happened to the sacrifices we are commanded to give every day, every holiday, every year?

My instinct to understand modern sacrifice as action is another piece of that radical first century transformation:

"Rabban Yohanan ben Zakkai once was walking with his disciple Rabbi Joshua near Jerusalem after the destruction of the Temple. Rabbi Joshua looked at the Temple ruins and said: “Alas for us! The place which atoned for the sins of the people Israel through the ritual of animal sacrifice lies in ruins!” Then Rabban Yochanan ben Zakkai spoke to him these words of comfort: “Be not grieved, my son. There is another way of gaining atonement even though the Temple is destroyed. We must now gain atonement through deeds of loving-kindness.” For it is written: “Loving-kindness I desire, not sacrifice.” (Hosea 6:6)”

B e l l

In the final poem of the Book of Psalms, in the line before last, we hear two types of bells:

הַלְל֥וּהוּ בְצִלְצְלֵי־שָׁ֑מַע הַֽ֝לְל֗וּהוּ בְּֽצִלְצְלֵ֥י תְרוּעָֽה׃

Praise Her with resounding bells;

praise Her with loud-clashing bells.

What’s translated here as “resounding” is the Hebrew word Shama, like Sh'ma – to hear. Bells of hearing. This is the first type of bell we need. The one that brings us into the present and reminds us that what is happening in the world is simply human beings being themselves. Nothing unique about it. Like the buzzing of the flies.

What’s translated as “loud-clashing” is the Hebrew word T'ruah – loud cries. This is a word often associated with battle, the call of the warriors as they run into the battle field, or the cries of jubilation that welcome them after a victory. It is a sound related to action, to doing what needs to be done despite the danger, despair and pain. This is Hemingway’s bell that tells us: “Any man's death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.”

These are the two bells we need. Let’s find our center this Shabbat, and then let’s get to work.

B e l l

Before I sign off I want to make sure you know you are all invited to our final night of the Kumah Festival on Shavuot night, June 4th on a rooftop in Chelsea. It will be a special evening of re-interpreted Psalms, wonderful music, learning and wine. All the info HERE.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Misha

A Love Poem to the Soil

by Rabbi Misha

The South Indian spiritual sensation Sadhguru drove his motorcycle across the border from Jordan this week and made his way to Tel Aviv.

The Jordan Valley. Photo by David Shulman

Dear friends,

The South Indian spiritual sensation Sadhguru drove his motorcycle across the border from Jordan this week and made his way to Tel Aviv. He’s on tour to Save the Soil of the Earth, most of which has been degraded in dangerous ways, in a kind of offshoot of the climate crisis. He probably didn’t know that he arrived in Israel during the week when Jews are reading Parashat Behar, the Torah’s great love poem to the land, the soil, the earth itself.

It begins with Shmita, the seventh year, where (as we learned so beautifully from Liz Aeschlimann at our Shabbat a couple weeks ago), the land itself gets a rest:

“When you enter the land that I assign to you, the land shall observe a sabbath of יהוה.

Six years you may sow your field and six years you may prune your vineyard and gather in the yield. But in the seventh year the land shall have a sabbath of complete rest, a sabbath of יהוה: you shall not sow your field or prune your vineyard.

You shall not reap the aftergrowth of your harvest or gather the grapes of your untrimmed vines; it shall be a year of complete rest for the land.

But you may eat whatever the land during its sabbath will produce—you, your male and female slaves, the hired and bound laborers who live with you, and your cattle and the beasts in your land may eat all its yield.”

For farmers, following the laws of Shmita without the legal tricks the rabbis came up with to keep them from bankruptcy is not easy. But not following them is even more dangerous:

“Exile comes to the world for idolatry, for sexual sins and for bloodshed, and for [transgressing the commandment of] the [year of the] release of the land.” (Pirkei Avot 2)

It’s simple mathematics. Let the land rest and you can live off of it. Don’t, and you’ll be pushed off of it.

Next week’s Parashah we includes this:

“And you I will scatter among the nations, and I will unsheath the sword against you. Your land shall become a desolation and your cities a ruin.

Then shall the land make up for its sabbath years throughout the time that it is desolate and you are in the land of your enemies; then shall the land rest and make up for its sabbath years.

Throughout the time that it is desolate, it shall observe the rest that it did not observe in your sabbath years while you were dwelling upon it.”

The math couldn’t be clearer. The next part of the Parashah holds a more complex mathematical formula that is even more radical:

“You shall count off seven weeks of years—seven times seven years—so that the period of seven weeks of years gives you a total of forty-nine years.

Then you shall sound the horn loud; in the seventh month, on the tenth day of the month—the Day of Atonement—you shall have the horn sounded throughout your land - and you shall hallow the fiftieth year. You shall proclaim liberty throughout the land for all its inhabitants. It shall be a jubilee for you: each of you shall return to your holding and each of you shall return to your family.”

Every fifty years we are commanded not only to let the land rest in a stricter way than the seventh year, but also to relinquish whichever land purchases were made during that time. Real estate should not be tied to place, but to time:

“In buying from your neighbor, you shall deduct only for the number of years since the jubilee; and in selling to you, that person shall charge you only for the remaining crop years:

the more such years, the higher the price you pay; the fewer such years, the lower the price; for what is being sold to you is a number of harvests.”

There should be no such thing as ownership of land. A private beach, a private forest, a private waterfall – these are fantasies that should not hold standing in our reality. Even the notion of borders that keep certain people out of a piece of land denotes a type of collective ownership, which is, simply put, false. Our participation is such falsehood is a sin. “Those that preserve hollow lies,” said Jonah, “forsake their own mercy.”

The underlying principle of our relationship with land comes in the final climax of this redemptive poem of radical, impossible love:

כִּי־לִ֖י הָאָ֑רֶץ כִּֽי־גֵרִ֧ים וְתוֹשָׁבִ֛ים אַתֶּ֖ם עִמָּדִֽי

“For the land is Mine; you are but strangers resident with Me.”

The land does not belong to us. What is ours is temporary. The notion that we actually own anything is an expression of false pride. The Medieval Jewish commentator Rabbenu Bahya explains our stranger-resident-ness like this: “Don’t consider yourselves the main point.”

Observing these laws strictly is impractical. Letting them guide our way, however, is a gift that will help us be truly free, along with everyone else living on this soiled earth. As the Zohar says: “This is Torah, which is called Freedom. And that means the freedom of everyone and everything.”

Shabbat shalom,

P.S.

One way to actualize these ideas is to support our fundraiser for Black Women's Blueprint.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Jewish Detachment

by Rabbi Misha

Non-Attachment is generally considered a Buddhist notion. Jews tend to attach themselves to creatures and objects, then cling to them, and if possible, eat them.

Dear friends,

Non-Attachment is generally considered a Buddhist notion. Jews tend to attach themselves to creatures and objects, then cling to them, and if possible, eat them. That’s why it was surprising to me to discover that several different important medieval Jewish thinkers espoused the aspiration toward what they called “Prishut.” It was even more surprising to discover that when looked at closely, prishut should not be translated, as it often is, as abstinence, but as detachment.

The book I’ve been studying, Hamaspik Le’ovdey Hashem, strangely translated as The Guide to Serving God was written in Judeo-Arabic in Egypt in the year 1230 by Rabbeynu Avraham Ben Harambam, Maimonides’ son. In his guide R’ Avraham details each of the positive characteristics that will help connect a person with their God. To those of us less connected to the God paradigm, we might say these are the things that help bring us in contact with truth, goodness, peace, purpose; with our innermost self. This time of year, when we are counting each day of the Omer, is considered a time of preparation to receive the Torah on the final, 50th day of the Omer, the holiday of Shavuot. R’ Avraham’s list of positive characteristics could serve us well as a guide to examine how we are doing with these each one: Rachmanut – mercy, Nedivut – generosity, Arichut Apayim – forgiveness, Anavah – humility, Bitachon – security or strong faith, Histapkoot – contentment (with what you have), Prishut – detachment.

It’s certainly an interesting list, and each one is worth investigating. I’ll attempt to give over a sense of what he means by Prishut, since I was surprised to find myself agreeing with him that it can serve as a deep gift to each of us and to the world. If we can all muster some Prishut I think we will be much more prepared to receive the Torah in a few weeks.

R’ Avraham opens with a general philosophical statement:

“The physical world is a big wall separating the servant from her master.” There is a problem with physicality, he posits.

"Whoever is running after the vanities of this world, and desires to own them, such as money, property or honor, and who lusts for its pleasures, such as eating, drinking and sex etc, this person is wasting his time trying to get the physicality of these things and their uses, and his thoughts are anxious about them.... This type of person tends to be tired. Their dreams are filled with what they’re anxious about. They wake up at night and think about how to get the things they want. They take a break during the and find themselves thinking back at what they used to do and what they might do in the future..... If they get what they want, they either hide it away like misers or they spend all their time figuring out the many details of how exactly they're going to spend it.”

Those who are too focused on these physical things, says the rabbi, waste their time away in anxiety and an endless loop of meaninglessness. “הקץ לדברי רוח” said Job, “The end to matters of spirit.”

The one practicing Prishut, on the other hand “her heart is not occupied with the worries of the world, and she has space to contemplate the things that bring her closer to her purpose, and her hours are free from fatigue and hard labor because she uses them to work on what brings her closer to God, and what is necessary for living in this world, such as 'bread to eat and clothes to wear.'”

You’re beginning to see why my study partner Michael and I preferred to translate it as detachment. There is a freedom that prishut can offer us, to be with what is beautiful and good with no guilt about the fact that we are there and not with the problems of the world. There are even those times in which we manage to allow ourselves out of our own problems and agonies, and escape into the open meadows of good feelings.

But this type of detachment is not disengaged. It’s not the detachment of monks or hermits, but of those living and moving through the world. The word Prishut comes from the same word as perush, or interpretation. In Torah study, a parshan, or interpreter must go into the text, sift through the various meanings that seem to be calling out from it, find the heart of the matter and bring it back out to pass on to others. That is the act of Torah study, and the act of being a part of this world. R' Avraham writes:

“The principle of detachment is that it comes from the heart, meaning that the heart is detached from the love of this world and distancing itself from it.”

Remember that when R’ Avraham uses the phrase “the world,” he means the physical rushing buzz of meaninglessness that is constantly calling out for our attention. The essence of the detachment is the ability to stay above that, while living an earthly life. This is an engaged detachment, which includes the mercy, forgiveness, generosity, faith and contentment that he laid out in previous chapters. It is the difference between the fear of something happening, and the dissipation of that fear when that very thing takes place. We could live in the fear and anxiety, or we could try to imagine what we're afraid of in concrete terms, and more often than not we will find the fear is illogical. It reminds me of my father describing feeling most free when he is arrested for civil disobedience when he’s out protecting Palestinian farmers from violent settler thugs. The arrest relieves him of the anxiety, and he feels at one with his purpose.

Perhaps the clearest indication of what this engaged detachment is comes in the sub-chapter called The Signs of True Detachment:

“In order to properly assess this matter you must notice how you feel about those physical things that you do not have, as well as your joy when they do finally arrive. If you find that what you were lacking from the things of this world doesn’t change your inner world, and you’re not worried about not having them, and you’re not anxious to acquire new ones – know that your detachment is true.”

If you were waiting for that Amazon package to arrive, and going crazy with anticipation or annoyance, checked the delivery status 6 times, and felt wronged by not having it – you're not doing too well. And if when it arrived you got very excited, stopped everything you’re doing and felt the giddy joy of the fulfillment of what you deserve – you're also not doing so well. But if you ordered what you ordered and lived without it at peace, and felt pleased but not all that different when you opened the box – well then you’re doing great! It’s sign that you are closer to contentment, to peace, to the truth of the transitory nature of life and death, to the acceptance of this world for all its beauty and horror, to the generosity of nature and the sweetness of being a human being, to the understanding that we call needs aren't always such, to the eyn-sof, the never ending never beginning essence of it all. That’s where we want to be when we accept the Torah, and its teachings of action, justice and love.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Misha

On the Difficulty of Rest

by Rabbi Misha

I’ve been exhausted all week. No amount of sleep seems to be enough. Nor caffeine. Until Monday morning I was full of energy, the house felt alive and filled with hope. As the news of the leaked draft began to sink in, so did my energy sap. The atmosphere seemed to cloud.

Dear friends,

I’ve been exhausted all week. No amount of sleep seems to be enough. Nor caffeine. Until Monday morning I was full of energy, the house felt alive and filled with hope. As the news of the leaked draft began to sink in, so did my energy sap. The atmosphere seemed to cloud. A great feminist I know was reported to have admitted to feeling like her life was a waste. I ask a friend “how are you” and the description of the state of the world that comes in response cuts through me. And I can’t seem to find any rest.

Maybe this just isn’t the time to rest. Maybe this is the time to get down to DC, or further south where women’s rights over their bodies are already under serious attack or go out into the streets to make some noise.

Or maybe it’s a good moment to imagine how difficult it is for people with real threats to their freedom, those who live with ongoing oppression, disenfranchisement and fear to rest. I, after all am a New York City, white-presenting, straight middle-class man. Though the issue is personal to me and my family, as I’ve expressed to you before, the threat to me is theoretical, philosophical, improbable to impact me and my body. And yet I can’t seem to rest this week. I can imagine being a woman, this week and always, and the impact that fact might have on my ability to rest. I can imagine being Trans or gay or gender non-conforming and how that might impact my ability to rest. I can imagine being black, or Muslim or Ukranian or Palestinian or carrying multiple categories of oppression, and how that might impact my ability to rest. The anger, despair, sadness, confusion and fear that oppression creates must impact a person’s relationship with rest.

I can relate to the black feminist icon Florynce Kennedy’s words: “dying is really the only chance we'll get to rest.”

And yet, we are commanded to rest. Over and over by penalty of death. Don’t work on Shabbat. Rest. Relax. Enjoy. How might we do that today?

We might do well to take in Audre Lorde’s words:

“Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.”

Shabbat is the gift of obligatory rest. It wrests us from our minds, our frustrations, our madness and rage and commands us to rest. Shabbat, Lorde teaches us, is political warfare.

That’s what we will be doing this evening, in the painfully timely and deeply exciting Kumah event organized and led by women in the community and dealing in large part with bodily autonomy and the notion of rest. There will be many inspiring women playing a part, including poet Erica Wright, community organizer and chaplain Liz Aeschlimann, midwife Sylvie Blaustein and singer Judi Williams. And we be honored by the presence of the women who lead Black Women’s Blueprint, the organization that inspired the event.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Time To Rise Up

by Rabbi Misha

In Talmudic fashion, artist Ghiora Aharoni views shattering as the beginning of creation. The Brachot tractate tells us what it means when something breaks in a dream.

Dear friends,

Today, the day on which Jews around the world commemorate the Holocaust, is the day on which our spring festival, The Kumah Festival opens. We didn't intend to do this, but when the plans aligned in this way we felt it was a better plan than we could have come up with ourselves. What does one do with the act of remembering such a darker than dark time? What does one do with the broken shards of their history? With the broken pieces of her soul? Our answer this year is to to come together in an art studio to take in the work of a Jewish artist whose main material is the most fragile of all, glass.

In Talmudic fashion, artist Ghiora Aharoni views shattering as the beginning of creation. The Brachot tractate tells us what it means when something breaks in a dream.

"One who sees eggs in a dream, it is a sign that his request is pending. If one saw that the eggs broke, it is a sign that his request has already been granted, as that which was hidden inside the shell was revealed. The same is true of nuts, cucumbers, glass vessels, and anything similarly fragile that broke in his dream, it is a sign that his request was granted."

Breaking, the rabbis imply, is the release of energy of good things to come, like the breaking of the glass at a wedding.

That doesn't mean we let go of the brokenness. Like the Hebrews carried the broken tablets around the desert, Ghiora includes any shards of glass that broke during the artistic process in the final sculpture in what he calls a Geniza, or a sacred trash container (which is also, of course made of glass). But that Geniza is not necessarily painful, but an increaser of joy. One of his sculptures, which we will see this evening, is inscribed Genizat Sasson, A Geniza of Joy. Jewish history, even Jewish life as a whole might be boiled down to the ability to contain these two opposites, through the act of creativity in the shadow of death.

The following event in the Jewish calendar can be seen as a type of mirror image of this idea. Yom Ha'atzmaut, Israeli Independence Day is, on the face of it a happy day. It wants to be about life and strength. But in the 21st century it can't do that without carrying deep and troubling complexities. We know that with all the incredible things happening there,1948 was the beginning of a continuing catastrophe for the Palestinian people, that Judaism and nationalism fused there since in sometimes scary ways, that Israelis live with fear, and that the Jewish State is a battleground for what being Jewish stands for.

One of the now classic films about the Israeli occupation, which many consider to be the core of the problem there is Ra'anan Alexandrovitch's The Law in These Parts. Through interviews with supreme court justices, politicians and military leaders, the film is an in depth examination of the legal system in the Occupied Territories. Our Kumah event to mark Yom Ha'atzmaut will be a discussion around this film with a person who embodies the triangle of faith-art-politics that the festival is devoted to. Professor David Kretzmer is a religious Jew, whose faith drove him to be a founding member of several of the most important human rights organizations in Israel, including the Centre for Human Rights, the Association for Civil Rights in Israel and B'Tselem. His writing played a crucial part in the creation of the movie, and led to some of the questions posed to the justices in the film. Professor Kretzmer teaches a class on the film every year at Hebrew University. Sign up HERE to get the link to watch the movie before Sunday, and then to join our conversation via Zoom.

Two days later The New Shul is proud to join with dozens of Arab, Jewish and international organizations as sponsors of the Joint Israeli Palestinian Memorial Day Ceremony.

The Joint Memorial Ceremony is the largest Israeli-Palestinian peace event in history. Last year 300,000 people participated in the live broadcast event and over one million people streamed it afterwards. It has become a focal point for the entire peace community. Nearly every peace-building NGO in the region participates in some way, and we are proud to be sponsors of the Ceremony this year! It has a profound impact on everyone involved in or witnessing the event.

The Joint Ceremony sets the foundation for widespread cultural change by shifting public opinion on a mass scale. Joining together to mourn each other’s pain challenges the status quo, setting the foundation to build a new reality based on mutual respect, dignity and equality.

Kumah means Rise Up, and that is what we believe these events will help us do. I hope you all can join us in these glass-breaking events. It's time to release the spring's energy of healing, newness and hope.

For more information and to register go HERE.

And to register for the Joint Ceremony go HERE.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Becoming Earth

by Rabbi Misha

A few days ago, I took the boys on a pilgrimage to Leonard Cohen’s gravesite in Montreal.

Dear friends,

A few days ago, I took the boys on a pilgrimage to Leonard Cohen’s gravesite in Montreal. We winded our way up and down Mount Royal, crossed some Canadian mud patches with only one ruined pair of pants, navigated through one Catholic cemetery, then another. Along the way we discussed the nature of these places, where we bury our dead.

“Don’t step on the gray stones!”

“Why not?”

“Because there are people buried under them?”

“So?”

“Each one of them was buried by people who love them, and we respect that love by not stepping on the graves.”

“Are they skeletons?”

“It depends how long they’ve been there.”

“Do we all become skeletons when we die?”

“First our skin becomes part of the earth, then our flesh, and then we are like skeletons for a while. But it’s not really us, just what’s left of our bodies.”

As a parent, I find this moment liberating. I question myself, talking this way to a five-year-old, but the anxiety I used to pick up from him on this topic is absent now. Maybe the matter-of-fact way his older brother talks about the role of worms and their digestive system helps normalize the inevitable.

“We’re going to the grave of one of the most famous Canadians ever,” I tell them.

“What is he famous for?”

“Guess.”

“He invented something,”

“No.”

“He was a sports star.”

“No.”

“The president of Canada?”

“They don’t have those here. And no. Keep thinking.”

Finally, we arrive at the Gate of the Heavens Cemetery (Sha’ar Hashamayim). We examine one “Cohen” grave, then another, and another as we look for Leonard’s. Some of them have stones placed on them, a practice which I also try to explain to the boys. None of the graves, however, have the different type of Star of David we’ve been instructed to find. Different in what way, we’re not exactly sure.

Finally, we detect a gravestone completely covered in little stones, along with flowers, laminated letters, pencils, pieces of art and other little gifts left for the dead man. Ezzy confirms that it’s got the right name written on it, and below the name indeed we find a different type of Star of David. Instead of triangles, hearts link themselves as they move in and out of one another. A gentle transformation of nationalism into love.

“So what was he famous for?”

“He wrote songs and poems.”

“That’s it?”

“You see all those things people left on his grave? That’s because music is one of the greatest gifts a person can give. That’s why he’s so loved.”

While Ezzy and Manu begin gathering sticks as their gift a few more pilgrims come by. We stand in front of the humble gravesite, looking at the stone in English and art, and the smaller one at his feet in Hebrew, with his Hebrew name and the letters תנצב"ה, an acronym for the words: “His soul be tied into the chain of life.”

One of the pilgrims describes poetry readings in downtown Montreal in the seventies, where Cohen would be accompanied by piano. “Appropriate to come here on Passover,” he says.

I tell the boys they know one of his songs, and we all sing Hallelujah together. As we begin our walk back up the mountain, I ask them what they think he meant by “the holy or the broken Hallelujah.”

Manu knows the answer:

“A holy Hallelujah is when you say it at a holiday and you’re so happy that you just say it. A broken Hallelujah is when you say it when you’re sad because something bad happened, or frustrated, or angry.” Five-year-old wisdom for the ages.

We walk and talk about some ancestors that I knew but they didn’t, and others neither of us knew, pass back through the Canadian mud, this time unscathed, and back to the car, pilgrimage completed.

In the Haggadah we sing: “All my bones will say: Who is like You?” Does that happen up here or down there?

This Earth Day I ask: Aren't we lucky that we will one day become part of the earth?

Shabbat Shalom, Chag sameach and happy Earth Day,

Rabbi Misha

Four Cups of Redemption

by Rabbi Misha

Dear friends,

Wishing you all a beautiful Pesach. May the shackles slip off easily, the Matza Balls float with perfect fluffiness and Elijah appear in drag.

P.S The first Kumah Festival event, with artist Ghiora Aharoni was changed to April 28th.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Patience, Dignity and Redemption

by Rabbi Misha

Something beautiful took place this week in Albany. Seniors and disabled people joined their home care workers to occupy the capital demanding a living wage for home care workers.

Seniors, people with disabilities, home care workers and activists singing and risking arrest this week in Albany.

Dear friends,

Something beautiful took place this week in Albany. Seniors and disabled people joined their home care workers to occupy the capital demanding a living wage for home care workers. Most of us have had a chance to see home care workers in action. It’s a hard job, demanding constant compassion to go along with the expertise and physical strength required. It’s a job that you choose out of some movement in your heart. In New York especially, it’s a job that you don’t often choose out of rational reasons, since many of the workers get paid just over $13 an hour, less than working at a fast-food restaurant.

Yesterday, Sadie, whose Bat Mitzvah is coming up told me she sees her Torah portion as a story of renewal after a disaster. She likened it to coming out of the pandemic and shared with me what she thought we were supposed to have learned from these last two years, lessons about time and what to do with it. When I asked her whether she thought we actually learned lessons as a society she smiled sadly. “Not really.”

Half an hour later I turned on the radio to hear that despite bi-partisan votes in big majorities in both houses of congress in favor, Governor Hochul refused to add the Fair Pay for Homecare Act to the annual budget. Instead of the 150% pay raise needed, she gave them $2 extra per hour. I immediately thought of the nursing homes ravaged with Covid, the seniors and disabled folks who spent months alone in their homes, the shame I felt at the surfacing of our society’s utter failure to follow the biblical dictate: והדרת פני זקן, Ve-Hadarta Peney Zaken, or “Bring honor to the face of the elderly.” Instead of “hadar”, this Hebrew word that implies a shining beauty, the glory that we are instructed to recognize in our beautiful, wise and loving elders, we too often tuck them away to suffer in the dark.

Locally, we are in a crisis with regards to home care. Currently at least 17% of people in NY state who can’t function on their own simply can’t find someone to hire to help them. Lots of those that do, have help only part of the time they need it. The current situation forces people who don’t need to be in a nursing home to make that move, or others to live without basic hygiene practices. This is just one of hundreds of posts that express the absurd situation people are living in.

With all of this, I still find great inspiration and hope in what happened this week. These people in tremendous need, as well as underpaid essential workers broke through the mold of despair and complacency and worked for their own and others’ liberation. With the support of activists from JFREJ (Jews for Racial and Economic Justice) and other organizations they made a major change in public understanding of this issue. Two years ago, this was not on any politician’s radar. Now there are the buds of real results, which – thanks to the work of God they did this week - I have no doubt will mature into a tenable situation soon.

Redemption, this sweet state of mind of peace, lack of worry, and happiness, is a process. It appears in glimpses. The whale appears on the surface. We see it and know it’s there, and know it will come again. If we concentrate, wait, and go to the right place we will see it again. In that moment when she breaches and our hearts leap, we know all is right in the world, all is right with our soul, all is right with God. That is the moment we witnessed this week in Albany. Those who are in dire need came out to teach us how to ask for help. They sang, they spoke to people, they made beautiful noise; They let God’s words speak through them: “I have heard the cry of my people.”

This is Passover. That our friends, families and neighbors are cared for. That those who work hard do not slave away but get compensated fairly and feel our gratitude. That every one of us retains their dignity from birth to death. What else could redemption possibly mean?

At Hebrew School this week, six-year-old Anna asked an amazing question. “What happened to the Egyptian families whose sons were killed in the tenth plague? What was it like for them after the Hebrews left?” “Why didn’t God just transport the Jews to Israel instead of making the Egyptians suffer,” 9-year-old Elias chimed in. They were answered decisively by 10-year-old Pearl: “God can’t do everything for us. God needs us to learn how to liberate ourselves.”

That answer, perhaps, is what redemption might mean.

My sister-in-law, Audrey Sasson, the ED of JFREJ was up in Albany all week. She had this to say a couple days ago:

“I couldn't be prouder to be a Jew for Racial & Economic Justice. Like Sylvia, Jenny, & Sara, (three of the senior and disabled protestors) I'm in this to build the world of our most liberated dreams. We won't stop organizing til everyone has the freedom to thrive.”

We have redemptive work to do. We have redemptive patience to find as we go. And we have moments of redemption along the way. Hallelujah.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Many of the protesters are still in Albany, refusing to leave until fair pay is approved.

Weaving Project

Images from our Weaving Project

What a wonderful and creative time we had yesterday on our Weaving Community Project at Tick Studio.

Don't Try, Praise!

by Rabbi Misha

In order to praise our existence with a full throat one has to be a prophet, a poet or suffer from some other form of insanity.

By Itamar Dotan Katz

Dear friends,

In order to praise our existence with a full throat one has to be a prophet, a poet or suffer from some other form of insanity. Today, with the sophisticated ways of modernity, the ancient way of a complete succumbing to wonder, is too often replaced with a complex type of praise. “Try to praise the mutilated world,” wrote the Lviv born poet Adam Zagajewski. Not only does the poet relieve us of the need to see the perfection of the world by calling it mutilated, he also instructs to “try to praise,” rather than to praise. This seems somehow more doable than “Let every breath of life praise Yah – Hallelujah!”

19th century German Rabbi, Samson Refael Hirsch explains this line from Psalm 150 as follows:

“Let every breath hear, recognize, sense and perceive God in all things that life may bring, in the serious introspection of solemn moments as well as in pensive meditation; in the widespread rejoicing of public jubilation as well as in the quiet serenity of inner happiness; in the unexpectedness of great surprise as well as in the stirring force of profound emotions: Kol Haneshamah tehalel Yah, Hallelujah!”

This is a mammoth task. Unattainable really. A prayer or intention rather than a conquerable assignment. How in the world might we reach such a state of profound acceptance of the often-invisible justice of the universe?

Let’s try another modern poet/lunatic, one Mr. Cohen. He suggests the following approach:

I did my best, it wasn't much

I couldn't feel, so I tried to touch

I've told the truth, I didn't come to fool you

And even though it all went wrong

I'll stand before the Lord of Song

With nothing on my tongue but Hallelujah

Now there’s a perfection we can recognize, because it’s the story of the failure of all of our lives. Still, despite our own failures and despite the continued failure of God - or perhaps thanks to it - we praise. Well, there’s some praise we can get behind!

No. We can do better. It’s in our DNA. Praise to Jews is like snow to Eskimos. We have an endless spring of words for it. Surely one of them can suit us.

Hirsch explains שבח, perhaps the first word that comes to mind as Hebrew for “praise:”

“שבח is to acknowledge the value, which the acts of another have with regard to ourselves.” When the Psalmist wrote שבחי ירושלים את יהוה, Jerusalem – praise YHVH! He meant that the residents of Jerusalem should acknowledge the acts that God has done for them. Each of us does achieve moments in which we can truly acknowledge what God, or the universe, or the totality of our lives have led to: and know it is good. We manage here and there to un-qualify our positive statements and simply know – our lives are beautiful. Almost every single Bar, Bat or B Mitzvah I’ve led has produced that very tangible feeling that you can witness in both the person at question and their parents.

Another Hebrew word in the realm of praise is Baruch, blessed. Baruch atah Adonai, we say, Blessed are You, Adonai, and we mean something that transcends complexity and upholds unquestionable goodness. There is a rabbinic method of midrash, in which the vowels of a word are changed around, while the letters remain the same, and that allows us to uncover a different meaning buried within the same word. Don’t read Baruch, we might say, but Be-roch. Blessed is suddenly transformed into “with gentleness.” With gentleness You are, Adonai our God. Everything You do is gentle, loving, sweet. Some might say this is more of a desire than a reality. Or we could, for a brief moment, know it to be a truth. Despite the rough, violent appearance, the reality of God is gentle.

There is, however a deeper concept of praise that is expressed by the Hebrew word “Hallel,” the type of praise that we conjure when we use the word “hallelujah.” Hirsch explains:

“Hallel denotes a proclamation of the greatness of another’s acts quite independently of the value that such acts might have for us.”

When we praise in the form of Hallel we divorce ourselves from any benefit we might have received from these acts, and simply offer praise because the actions are praiseworthy. The “I” that utters the praise dissolves into a selfless ability to witness beauty and goodness.

Thomas Merton hits this note in a poem he called O Sweet Irrational Worship:

By ceasing to question the sun

I have become light,

Bird and wind.

Every Rosh Chodesh, the first day of the Hebrew month, we connect to this type of praise through what is called the Hallel service. At our Shabbat service this evening we will welcome the new moon of the Hebrew month of Nisan with a search for this ancient, full throated, selfless praise for the world we live in.

I hope to see you this evening at 6:30 at the 14th Street Y, or on Zoom.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

A note to the Pope from the south of Spain

by Rabbi Misha

I have never considered writing a letter to the Pope until yesterday.

The Mezquita in Cordoba

Dear friends,

I have never considered writing a letter to the Pope until yesterday. I was sitting in The Mezquita, an incredible church-mosque complex in the Andalusian city of Cordoba. Being in a space that Carries the intertwined prayers of Christians and Muslims from the last 1500 years inspired me to put some words together to send to Pope Francis. It is likely in need of some revisions before I send it, if I ever do. But I share it with you this Shabbat and send you blessings from this marvellous city of our ancestors.

Your Holiness Pope Francis,

I write to you with awe from the holy grounds of the Mezquita in Cordoba. I sit here surrounded by the great oneness of the God of all people who have prayed here for centuries, Muslims, Christians and visitors of all faiths. As I write, bombs fall on Ukraine, again the bloody hatred of selfishness emerges, consuming lives like fire. But here in the Mezquita one can hear the sweet singing together of two faiths that have been at war many times.

This city was home to my people as well. Our great sage and teacher Rabbi Moses Son of Maimon was born and educated here during what is known as the Jewish Golden Age of Spain. Most of his books he wrote in Arabic, and reflect a deep relationship with his Muslim brethren. This “golden age” was, sadly not always so glowing for the Jews. Maimonides was likely forced to flee Cordoba when the Muslim ruler threatened his family with death if they did not convert to Islam. The church was no different, and ended our golden age with the forced expulsion of the Jews in 1492, after killing and converting many. While the Mezquita and its Muslim splendour have been preserved, little remains in Spain of the hundreds of years the Jews spent here, beyond the memories carried in the walls of the Juderia, and the writings we have preserved.

This is a time of war. This is also a time of opportunity. The church under your leadership has shown the loving face of God to the world. I write with a petition that is so remote that I more accurately call it a prayer.

Sitting here in this beautiful house of God, the coming together of two traditions, I can’t help but feel the missing representation of the faith both of these traditions violently crushed in Spain. What a testament it would be to the human ability to love if a small Jewish space were to be included in the Mezquita. What a powerful message that would send against war, against hatred, against division. What a lesson that would offer the world about our ability - even our responsibility - to repent, to make Teshuvah, to come back to the truth and to the peace of God.

I imagine the tiny Jewish enclave in this magnificent temple, and am filled with love and gratitude. This is the feeling that such a gift would fill Jews worldwide with. A gift to the Jews of the world, that would inspire generosity from all peoples.

I know that the local Muslims have petitioned to be allowed to pray in the Mezquita and were denied some years ago by the Vatican. This denial may make it more difficult to give a gift to the Jewish people in this time. My community and I would absolutely support such a request on behalf of the Muslim community here, were it to be considered again. I am certain there would be wide Jewish support for it. I have spent much of my life seeking meaningful partnerships with Palestinians that might bring about peace and reconciliation between Israel and Palestine. Such a gesture by the church toward both Jews and Muslims here in Cordoba would certainly provide an important boost to the efforts of the peace movement in Israel/Palestine.

I imagine a space where all three faiths can pray in harmony, and I feel at home in the world again.

“כי ביתי בית תפילה יקרא לכל העמים.”

“My house will be called a house of prayer for all peoples,” said Isaiah.

This is a time for giving, a time for fraternity, a time for the oneness of God to shine. Where better a place to allow it to happen than in the land where civil war tore everything apart after many generations of different faiths learning from one another and influencing each other to love God.

Humbly yours,

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Zelensky Speaks

by Rabbi Misha

Voldymyr Zelensky, in the spirit of the Bíblical prophet, Amos, seems to declare, “I am no prophet nor the son of a prophet. I am a comic actor who was visited by a dream which has overtaken my life. The lion has roared; who can but tremble? The Lord God has spoken; who can but prophesy?”

Dear friends,

Thank you to all of you who came to our uplifting Purim celebration this week. It's so important to celebrate and make merry, especially now. What a fun night! That day began with Zelensky's address to congress, including the devastating video he shared, and ended with a drunken Purim bash, Mariah Carry songs from Chanan and all of us singing I Will Survive. On the train on the way to the party I read a note my rabbi, Jim Ponet sent me. He captured something deep about the connection between the holiday and the horror, between the experience of taking in Zelensky's words in the morning, and celebrating Purim at night. I share his words with you:

Voldymyr Zelensky, in the spirit of the Bíblical prophet, Amos, seems to declare, “I am no prophet nor the son of a prophet. I am a comic actor who was visited by a dream which has overtaken my life. The lion has roared; who can but tremble? The Lord God has spoken; who can but prophesy?”

The U.S. Congress heard Zelensky allude to MLK, to 9/11, to Mount Rushmore as he begged American leaders and the American nation to help bend the arc of history toward justice, to inspire the world to mobilize for peace, dignity, health and freedom, to refuse to ignore the voice of the oppressed

We have again heard the voice of God, issuing this time from a prophet speaking Ukrainian and English, addressing us from Kiev via video. And like dreamers we and our political leaders listened spellbound to the call to help halt the military invasion launched against the civilians of Ukraine by Russian troops, tanks, missiles, planes and drones at the command of a single man. And in that voice we discerned an echo of the cry from Minneapolis that yet resounds from the throat of George Floyd as a cop’s knee bore down upon his neck, the fierce anguished call to feel, attend, respond, and act with whatever we got.

Out of sheer terror the ancient Israelites fled from that call, sought escape from the summons of the Voice. But Zalensky, like Moses, Esther and Abraham, somehow dares to stand alone and face down the Leviathan like a Job refusing to cower before autocratic whim, even if it be divine: “He may kill me, but I won’t stop; I will speak the truth to his face.”

Zelensky and the Ukrainians are fighting to breathe. When we are in our right minds, we are all together in that fight for life and freedom, knowing it is why we are here after all; namely, each to find their own response, their own mode, their own language. As we allow unbearable truths to confront us, we would do well to consider Nathaniel Hawthorne's observation that while weeping passively in the face of spiritual and physical ugliness is understandable it would be better for us, if we can, to burrow toward "the fiercer, deeper, and more tragic power of laughter." Voldymyr Zelensky points the way.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

From UJA: Ukraine Response

From UJA: Ukraine Response

The war in Ukraine continues to escalate, and the humanitarian crisis is catastrophic. More than 2 million Ukrainians have fled to neighboring countries. The European Union estimates that refugee numbers could top five million -- a number that includes tens of thousands of Jews -- making this the largest refugee crisis in Europe since World War II.

At the same time, tens of millions of people remain in Ukraine, including many of Ukraine’s 200,000-member Jewish community. Families, children, Holocaust survivors, and the homebound elderly -- especially those who have been displaced multiple times -- are trapped or enduring limited access to food and water and are facing imminent humanitarian devastation.

Ukrainians urgently need our help.

Since the first days of the invasion, UJA has been working 24/7 with our partners utilizing our expertise and on-the-ground network to provide humanitarian aid and evacuation assistance to the Jewish community including those who want to make aliyah -- and for hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians in desperate need.

Thanks to your generous support, to date we’ve already allocated $5 million in emergency funding to provide urgent assistance and relief. We're coordinating with partners who have expertise and systems already in place in Ukraine and its neighboring countries, grassroots organizations that can nimbly reach those in dire need, and international disaster response and refugee support organizations.

Learn more about our work on the ground.

If you were unable to attend our latest briefing yesterday that included a powerful eyewitness update from our CEO Eric S. Goldstein who just returned from Poland, you can view the recording here:

Though thousands of miles separate us from the Jews of Ukraine, the bonds between us are inextricable. We pledge to stand by their side, providing every kind of assistance we can through the dark days of this crisis.

Thank you for your support.

Odessa

by Rabbi Misha

We carry the incredible gifts of this city everywhere.

Ahad Ha'am with other literary giants in Odessa in 1906.

Seated from left to right: a young rabbi, Lilenblum, Ravnitsky, Ahad Ha'am, Mendale Mo"s, Levinsky

Standing: Borochov, Klauzner, C.N Bialik

Dear friends,

133 years ago last night, a fire broke out in a schnapps distillery in Odessa. The distillery’s manager, also the son in law of the owner had other plans that night. But Asher Zvi Ginsburg rushed to the distillery that he hated running. He tried to assure his father in law that he will find another way to support the family as he witnessed his livelihood turn to dust. Then, some time after midnight he made his way through the empty streets to an apartment where seven friends were anxiously awaiting his arrival.

“Children of Moses,” he opened, “today he was born, and today he died. Moses, master of the prophets, man of truth, whose soul, words and deeds were governed by the rule of absolute justice.” The seventh night of the Hebrew month of Adar Bet was chosen as the appropriate night for the creation of a secret society by the name of The Children of Moses, which would work toward the establishment of a movement to prepare the hearts of the Jewish people for a new type of nationhood.

“We aim to expand the understanding of peoplehood, turning it into a lofty and noble concept, a moral ideal, in the heart of which lies the love of Israel, and which encompasses every good attribute and every honorable property; we will strive to liberate the word “national” from the heavy physical form it currently holds, and to raise it to the level of an ethical, respected and beloved concept in the eyes of the people.”

A tremendous excitement surrounded the eight participants. The atmosphere of “holiness and purity” led them to believe they were part of a historic event.

They took a vow, committing themselves to Zion: the ancient abode of peace and righteousness, of wide and open hearts, of boldness and courage.

“The hearts of our people must be revived. We must work toward the strengthening of faith and the awakening of desire through the power of love and the yearning toward meaning. This love - the individual’s love of the success of the collective - is not foreign to our people.”

The first members of The Children of Moses were silent as their leader paused.

“The heart of the people is the foundation upon which the land will be built. Not by might, nor power but by spirit.”

This gathering was but one example of the incredible energy and idealism the city of Odessa hosted for the Jews of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. This was where the Hebrew language came to life after a liturgical 2000 year long nap. It was where Yiddish literature came into its own, followed by the beginning of modern Hebrew poetry. Ahad Ha'am, the writer and thinker described (quoting his own words) above was the father what is known as Spiritual Zionism. Grown out of the soil of a traditional life, these prophetic giants created a new reality of art, political engagement and deeply rooted innovations of the spirit. Ahad Ha'am’s friend, poet Chaim Nachman Bialik, who was a member of one of the other secret societies in Odessa said the following astonishing sentence:

ארץ-ישראל בלי שבת לא תיבנה, אלא תחרב, וכל עמלכם יהיה לתוהו... בלי שבת אין ישראל, אין ארץ ישראל ואין תרבות ישראל".

“The land of Israel without Shabbat will not be built, but will be destroyed, and all your work will be for naught….. without Shabbat there is no Israel, there is no land of Israel and there is no culture of Israel.”

He would posthumously become the national poet of the State of Israel.

The passion these patriots exhibited, the type of genius they expressed, might be of an eastern wind. Their nationalism is different than the hard Zionism of Herzl and the Jews of Western Europe. Their dreams were softer, though no less audacious. And they saw that whatever power Jews might hold, be it political or of a different order, is worthless without a real relationship with Torah. The eternal is something we carry with us no matter where in the world we go. Our history walks with us as we walk. The children of Moses can hear his whispers: Love the stranger. Love your neighbor, Love God with all your heart.

As Russian bombs inch closer to Odessa we can lean back into our history and our teachings and know that bombing this precious city would not only be a war crime, as Zelensky called it, but a terrible crime of the heart; and that there are some things that are beyond the reach of bombs, fire and hatred.

May it be your will, Adonai our God and God of our ancestors that Odessa be spared, that the fighting cease, the wounded heal and the refugees find a place of comfort. That the wicked disperse, as is written in the Psalm for Shabbat: “I see your enemies, Adonai, losing their way, scattering, disappearing.”

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Know The Member - Hayley Antonelli

Get to know our members!

This time - Hayley Antonelli

Get To Know The New Shul Member: Hayley Antonelli

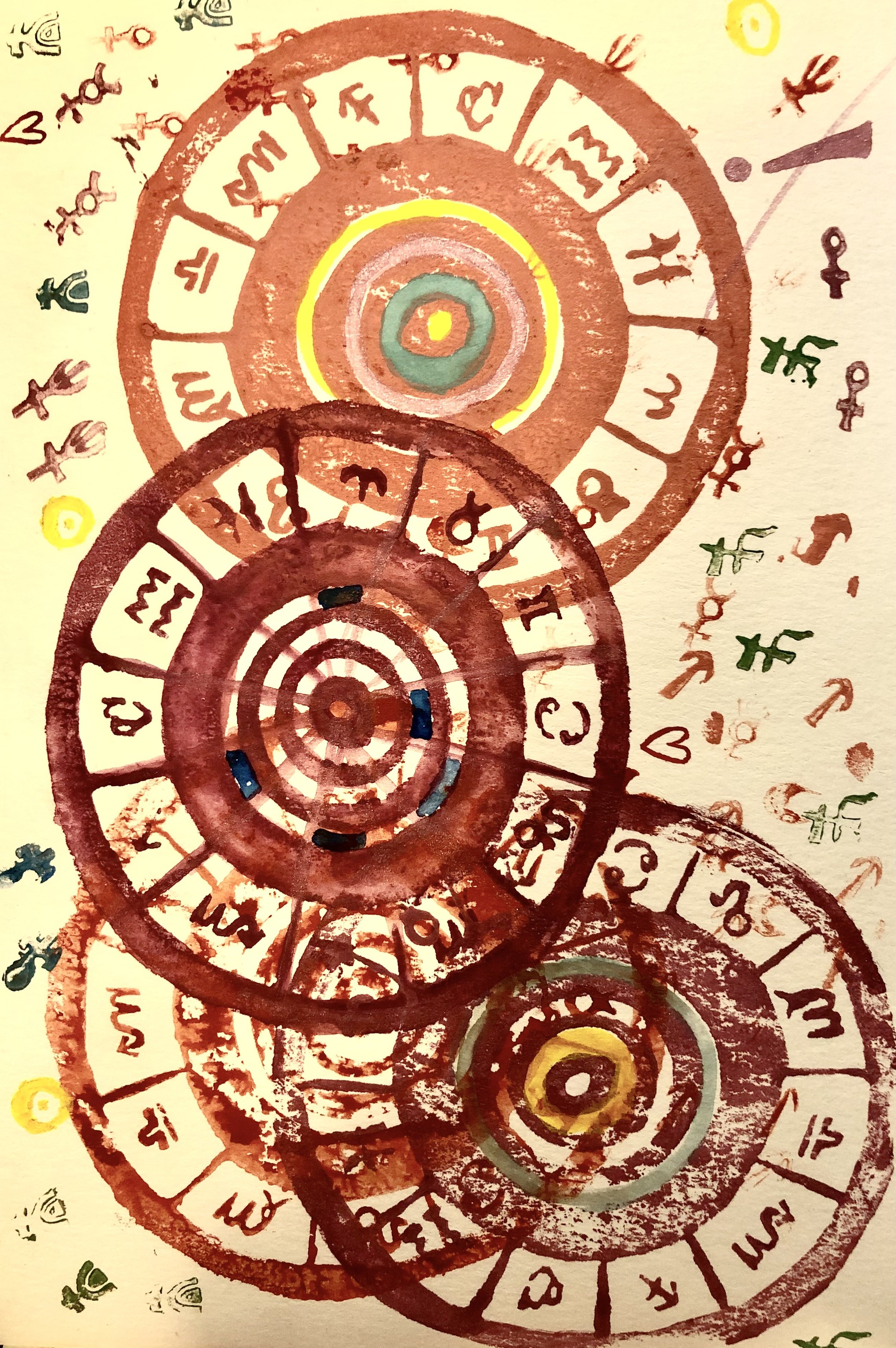

Hayley is a curious and motivated young professional, exploring fine art making practices, with special interests in art teaching, fine art publications, religious artifacts, and fine art apprenticeships. Additionally, she is researching contemporary religious studies, as well as Buddhism and Jewish histories. Outside of the academic setting, Hayley has worked extensively in the equestrian industry, providing world class equine care and teaching young riders.

Follow her on Instagram: @hantonelli_photography OR on her website: https://hayleyantonelli.squarespace.com/

What Home Really Looks Like

by Rabbi Misha

One week ago, there were one million less refugees in the world. One week of war creates homelessness on that vast a scale.

Photo by Itamar Dotan Katz

Dear friends,

One week ago, there were one million less refugees in the world. One week of war creates homelessness on that vast a scale.

I grew up with the presence of war. Every few years since I was five, my country of refugees would try and stop the nation of refugees we created when we started our country from attacking it, by making many of them refugees a second or third time. The refugee heart of the Jewish state made and makes it cling to its home with everything it’s got and anything it can get. The stateless, status-less Palestinians, who still carry the keys to their ancestral homes as the living symbol of their homelessness, need to claw their way back home, no matter how. Two nations living and reliving their homelessness. This was my home. My experience tells me that the million new refugees and the millions yet to come will develop a new mentality and pass it down for generations.

Hannah Arendt described what it’s like to be a refugee in We Refugees:

"We lost our home, which means the familiarity of daily life. We lost our occupation, which means the confidence that we are of some use in this world. We lost our language, which means the naturalness of reactions, the simplicity of gestures, the unaffected expression of feelings. We left our relatives in the Polish ghettoes and our best friends have been killed in concentration camps, and that means the rupture of our private lives. "

There is a mentality to the experience of needing refuge that is unique. This week, students in our Hebrew school interviewed their parents and grandparents about their family’s immigration story. I overheard Ezzy interviewing his grandfather Roby. Kicked out of Egypt in 1957 for being Jews, Roby and his parents ended up in Paris for a few years before moving to Italy, Israel and finally Canada. When Ezzy asked him how these experiences impacted his view of life, Roby described the decades that followed them, of never feeling at home. He always felt like a guest, even in his own house.

As Jews, we all have these experiences in our DNA. Most of us still carry the memory of being forced to flee. It’s hard to think of biblical characters who weren’t refugees. From Adam and Eve all the way to the end of the Torah almost every single one sought refuge. We carry a homesickness, an estrangement we can’t quite place or explain. My father-in-law's sense of being a guest doesn’t sound foreign to many of us.

Arendt continues:

"We were told to forget; and we forgot quicker than anybody ever could imagine. In a friendly way we were reminded that the new country would become a new home; and after four weeks in France or six weeks in America, we pretended to be Frenchman or Americans. The more optimistic among us would even add that their whole former life had been passed in a kind of unconscious exile and only their new country now taught them what a home really looks like."

The refugee in us lives in exile, whether consciously or not. “What a home really looks like” is one of the great questions of our lives.

One of the reasons I think this last week has been so painful to many of us, is because Ukraine plays a role in our story of what a home looks like. Many of our families lived there for generations. Two of the greatest positive pieces of contemporary Jewish identity were formed on the land now called Ukraine. Two different historical movements there, one in the 18th century (Hassidism) and the other in the late 19th century (The revival of the Hebrew language) – both stamped with the reality of anti-Jewish acts and the refugee mindset that those acts bring – created important foundations of true pride for Jewish people to this day. These pieces of our sense of home in the world are what I would like to explore with you this evening at our special Shabbat at the 14th Street Y. I am excited to connect, through music, story and conversation with these two historical movements that blossomed in Ukraine. I’m excited to feel the unity of Jews all over the US marking HIAS Refugee Shabbat. I’m looking forward to sending prayers and love toward Ukraine. I’m excited to introduce you all to a wonderful singer, Dana Herz. I’m excited to be IN PERSON with y’all again and come back home to Shabbat.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Immigration Stories

Learn how different families in our community migrated around the world

A Letter from Hazzan Hirschhorn

A Letter from Hazzan Hirschhorn

A Letter from Hazzan Hirschhorn

What comes to your mind when you think of Ukraine?

Perhaps it’s a place your ancestors fled in horror, after pogroms. Perhaps it's a place you visited in a more recent memory, to trace your family’s history. Perhaps it only became more familiar to you in the last weeks, with the flood of terrifying news of Russian impending, and then ongoing, invasion.

I think of Kyiv as a place where I, and at least three generations of my family, were born. The place where I went to elementary school and where I returned to study in a Kiev conservatory, a place where I still have friends, family, classmates, and teachers.

Kyiv is also a place where my grandmother lost her job at the Kiev Opera House after the arrest and murder of my maternal grandfather under Stalin in 1937, and where my great grandparents perished in Baby Yar. It is the place the German Nazis bombed at the beginning of the war, on June 22, 1941, which was my father’s sixth birthday. He was anticipating attending a soccer match with his Dad, who instead was called to the army, while my father managed to flee the city with his mother and aunt. My father never saw his Dad again. In my lifetime, I fled Kyiv twice, on my own. Once as a fourteen year old escaping the radiation from Chernobyl, and again, in 1992, when I finally had a chance to come to the US. My history with Kyiv is complicated, tangled, and often painful.

But I have also watched with admiration and pride when the citizens of Ukraine fought for their independence in the Orange Revolution, and built a democratic country that truly welcomes the Jews of all stripes, including Volodymir Zelenskij, its truly heroic president.

My friends and family members are now spending sleepless nights trying to escape Putin’s missiles, crowded in the Kyiv subway, or in their apartments, because they have elderly parents, who don’t have the mobility to flee or hide. They are watching the night sky light with explosions, and tell us when we call: “Don’t worry, we hear the fighting, but it has not hit us directly, Yet.” This is a horror we could not have imagined in our worst nightmare.

It’s easy to feel helpless in the face of such unprovoked aggression. Millions of lives in Ukraine are affected, including those of our fellow Jews, as Ukraine is home to one of the largest Jewish populations in Europe. The entire world order is disrupted. However, despair is not a solution. Here are a few things we can do. I hope and pray that our actions can and will bring real change. https://linktr.ee/RazomForUkraine

May the Merciful One guide our hearts and our hands to help diminish the immense pain and suffering in Ukraine.

Natasha

Hazzan and Music Director, Ansche Chesed