Sort by Category

Rise Up and Hope

by Rabbi Misha

War engenders despair. It gets in your head and speaks about your meaninglessness and powerlessness. It kills people as a means of killing hope. Which never works. Like life, hope continues.

Our hosts Steff and Ronnie at the Gotham Depot Moto, where we open the Kumah Festival this evening.

Dear friends,

War engenders despair. It gets in your head and speaks about your meaninglessness and powerlessness. It kills people as a means of killing hope. Which never works. Like life, hope continues.

Our Kumah Festival this year, which begins tonight, is a path to hope, a reminder of our ability to rise above the noise and rise up over obstacles of displacement, oppression, hatred and loss.

We begin this evening with the devotional music of the Jews of Turkey, who found refuge from the blood-thirsty Catholics of Spain not only in the lands of the Ottoman Empire, but also in its music. They countered despair with delight, death with poetry, wickedness with neighborly love. We will attempt the same with the music of East of the River, the food of Chef Sami Katz and the incredible motorcycle-filled space at Gotham Moto Depot.

Then on Sunday we will come back to the present with the Joint Israeli-Palestinian Memorial Ceremony. This is a sad gathering, there’s no doubt. But the beauty that comes every year out of the honest sharing of grief of those who are meant to be enemies is an antidote to any of the words of the sad excuse for politicians that we are used to hearing on these topics. Sharing sorrow, bringing hope, as the Bereaved Parents Circle, one of the leading organizations calls it.

The final two events on Thursday and next Saturday will approach the question of hope through two of the ancient ways human beings have used to stay focused on the right and the good: theater and mysticism. I am sure that this series of events will give us a lot of perspective, strength and energy to dive back into the burning task of ending this war and preventing the next.

See you tonight among the motorcycles!

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Real Peace

by Rabbi Misha

When the Holy Blessed One came to create Adam the first human, the ministering angels divided into various factions.

Daphna Mor and the musicians of East of the River will open our Kumah Festival on May 10th.

Dear friends,

When the Holy Blessed One came to create Adam the first human, the ministering angels divided into various factions. Some of them were saying: ‘Let him not be created,’ and some of them were saying: ‘Let him be created.’ This is what is referenced in the Psalms when it is written: “Kindness and truth met; righteousness and peace touched” (Psalms 85:11). Kindness said: ‘Let him be created, as he performs acts of kindness.’ Truth said: ‘Let him not be created, as he is all full of lies.’ Righteousness said: ‘Let him be created, as he performs acts of righteousness.’ Peace said: ‘Let him not be created, as he is all full of discord.’ What did the Holy Blessed One do? He took Truth and cast it down to earth, as is written: “You cast truth down to the earth.” (Daniel 8:12). The ministering angels said before the Holy Blessed One: ‘Master of the universe, what are you doing?! Let Truth rise up from the earth!’ As is written: “Truth will spring from the earth” (Psalms 85:12).

While the ministering angels were busy arguing with one another the Holy blessed One created Adam. He said to them: ‘Why are you deliberating? Adam has already been created.’

So much of the essence of the events of the last week are captured in this ancient midrash. Like the angels, we are passionately arguing over humanity, over Israel, while reality keeps flowing. From our American island we yell and scream, while in Gaza the madness is not theoretical. Hirsh cries out to us waving his mutilated arm. The Israeli Minister of Finance demands “total annihilation,” while the tanks line up on the border, and the two men leading this rabid tango continue to display their sick selfishness.

Last week I had a moment of pride, when Rabbi Abby joined other Jews, American and Israeli to try to deliver food to Gaza. They were stopped a couple kilometers from the border crossing, but for a moment the hollow words from the Seder: “Let all who are hungry come and eat,” were given some depth when Abby and the other Rabbis for Ceasefire spoke about the hunger across that border.

The truth is I’m hungry. Hungry for quiet, for humility, for a world that doesn’t constantly provoke the earth to spew us out. Nachmanides said that the difference between the land of Israel and anywhere else is that unlike other places, Israel vomits away the people who defile it through moral abominations. I’m not sure that’s only true of Israel.

Monday is Holocaust Remembrance Day, the day on which we recall when the Jews paid the price for the moral abomination called Europe. We are still recovering from that. Even 79 years after that war ended there are still close to one million less Jews in the world than there were in 1939. Each antisemitic chant pushes us further away from recovery. And each Palestinian child who dies too.

This week’s Haftarah is one of the clearest ethical rebukes of a nation, in a bible full of them. Speaking to Jerusalem, “the city of blood,” the prophet Ezekiel enumerates the moral, social and religious abominations of the Jews of the city – which he already knows will lead to the land spewing them out.

הִנֵּה֙ נְשִׂיאֵ֣י יִשְׂרָאֵ֔ל אִ֥ישׁ לִזְרֹע֖וֹ הָ֣יוּ בָ֑ךְ לְמַ֖עַן שְׁפׇךְ־דָּֽם׃

Every one of the leaders of Israel in your midst uses their strength for the shedding of blood.

The punishment is coming, says the prophet, the circle is coming around, and he urges the people to consider their frailty:

הֲיַעֲמֹ֤ד לִבֵּךְ֙ אִם־תֶּחֱזַ֣קְנָה יָדַ֔יִךְ לַיָּמִ֕ים אֲשֶׁ֥ר אֲנִ֖י עֹשֶׂ֣ה אוֹתָ֑ךְ אֲנִ֥י יְהֹוָ֖ה דִּבַּ֥רְתִּי וְעָשִֽׂיתִי׃

Will your heart be able to stand it? Will your hands still hold any strength in the days when I deal with you? Unlike you, I, YHVH, am not all talk.

Our fate, suggests the prophet is not sealed. Goodness could appear in a flash; as quick as regret, as sudden as a realization; “a flash of lightning,” as Nietzsche put it:

"Rendering oneself unarmed when one had been the best armed, out of a height of feeling – that is the means to real peace, which must always rest on a peace of mind; whereas the so-called armed peace, as it now exists in all countries, is the absence of peace of mind."

When our ancestors were kicked out of Spain they found refuge in Turkey. While their leaders debated how to stay alive - like the angels in the Midrash - the musicians offered peace of mind through the new music they encountered there. They were alive, they were singing, they were at peace. As we prepare to open our Kumah Festival next Friday with that very music, let the memory of the six million remind us who we are: a nation of wandering improvisors, whose weapon and saving grace has always been our imaginative mind. May we return to it and find a real peace.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Festival of Faces

by Rabbi Misha

In the second century in Palestine, after the failed Bar Kochva rebellion, the Roman Emperor Adrianus imposed harsh laws on the Jews that included forbidding the practice of the religion.

Dear friends,

In the second century in Palestine, after the failed Bar Kochva rebellion, the Roman Emperor Adrianus imposed harsh laws on the Jews that included forbidding the practice of the religion. Many Jews were killed in the decades leading up to these decrees and many more will perish. in the midst of the struggle, 10 rabbis left their dwelling in the Galilee and went into the forest at night. They needed to shift the spiritual gravity center of the world, which was off in dangerous ways. They saw how people were not seeing one other. They would look one another in the face and see nothing. The problem, the rabbis understood, stemmed from the same thing happening in the divine world. The two faces of the divine, the male and the female, the God and the goddess turned away from each other. If they could turn them to face one another, the realignment in our world would be felt, and people would once again be able to see one another’s faces.

Our world today seems to be suffering from a similar problem. Too many people are caught in frameworks of thinking that prevent them from seeing the simple humanity of the person in front of them. This is what happens in wartime.

French Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas came out of World War II with a new understanding about the face of the other. Seeing another’s face is the sixth commandment, “Do not murder,” he taught. Once you see the other, you step out of yourself and your natural selfishness and find care for another. It is, in effect, the opposite of the dehumanization that war causes.

Our Kumah Festival this year is a search for the ultimate antidote to killing, the human face, in the midst of war. Each of the four events of the festival will offer a different search for the human face, through the overlapping of art, faith and politics.

Possibly the most amazing face-seeking these days is being done by Combatants for Peace and the Bereaved Parents Circle, when every year on Israeli Memorial Day they produce the Joint Israeli-Palestinian Memorial Ceremony. This unique event has grown to become the largest peace gathering in the world, drawing hundreds of thousands of viewers to witness Palestinians and Israelis mourn together their dead, sing and search for hope. This will be the first year that the event on May 12th will include a New York component, in which I will join with other rabbis and artists to frame the ceremony. Once you have heard a Palestinian speak tenderly about their lost loved one it becomes impossible to categorize all Palestinians as a faceless group.

We tend to think of our history as though it taught us only to distrust and fear others, but that is far from the case. Between the struggles there were long periods of friendship and comraderie with other religious groups. One such moment came in the late fifteenth century. We were kicked out of Spain by the Christians, and many Jews made their way into Muslim controlled lands. A significant contingent of Spanish Jews landed in Turkey and were welcomed by the local community. The people we are conditioned today to see as potential enemies were then the face of our new home. On May 10th, East of the River Ensemble will perform for us songs from that time in our history, when those Spanish Jews learnt Ottoman melodies and created a new form of Jewish music.

The play Here There Are Blueberries, which we will watch on May 16, takes the challenge of the face to the extreme: can we see the face of our murderers, and what does that do to us? This important piece by Tectonic Theatre Company follows the brave work of Holocaust Museum researchers who found photos of Nazi officers on break from Auschwitz. After the performance we will speak with Amanda Gronich, co-writer of the lauded play, and Jonathan Raviv, one of the leading actors. Together we will explore both the gravitational force of the enemy’s face, and the danger that comes with succumbing to its charms.

I hope that when we arrive at our closing event on May 18, which leads us back to the forest in second century Palestine to join the ten mystics, we will be equipped to see not only the face of our enemy but even the face of the divine. With text from the Zohar made into art by the talented artists from Laba, that task should become approachable.

את פניך יהיה אבקש

Sang the psalmist, “it’s your face, YHVH that I seek.” Where else might we seek the face of god other than in the faces of our fellow human beings?

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

How to Do Passover This Year

by Rabbi Misha

Wishing you a happy Passover, a Zissen Pesach and Shabbat shalom.

Pre Passover Seder this week at our Hebrew School branch in Windsor Terrace

Dear friends,

Last Friday at Kabbalat Shabbat I chose to speak about how to prepare ourselves for Passover this year. Although in the background of what I said was the relationship between Jewish liberation and Palestinian oppression, I purposefully avoided speaking about the war head on, for the first time since October 7th. When the service ended Maia thanked me for my words but expressed dismay at the fact that I hadn’t named the difficulty this year. How could we celebrate freedom while we are killing tens of thousands and displacing millions? Everyone I know who will be at a seder this year is asking themselves a variation of that question. So instead of schmoozing, I suggested we sit down with whoever would like, to discuss it.

Of the many honest, thoughtful voices, it was Rene’s that stayed with me most. “In the camps,” she said, recalling her childhood escaping the Nazis, “people celebrated Passover. There was hunger – just like the hunger in Gaza today – so people took the horse feed, ground it into flour and baked Matzah out of it.” This short description cut to the chase of it all. Anyone there who thought that it’s impossible to celebrate Passover this year, immediately questioned their attitude. And anyone who thought they could ignore the war at their Seder this year couldn’t shake the Holocaust survivor’s clear-eyed comparison of the human situation in the camps and Rafah.

So how do we do it?

Ezzy was sick this week, which gave me a chance to read some of the Haggadah with him.

בכל דור ודור חייב אדם לראות עצמו כאילו הוא יצא ממצרים, he read.

“In each generation each person must see themselves as if they came out of Egypt.”

“Why,” he asked.

“What do you think it does, to imagine that you came out of Egypt?”

“Makes you appreciate what you have,” says Ezzy.

“Is that it?”

“It also makes you relate to other people’s suffering.”

I find these two pieces the keys to this year’s holiday. We can’t ignore the first one: the family and friends gathering, the joy of being together, the beauty of our traditions. Nor can we unhear the cries we have heard, the images we have seen, the situation our Palestinian brothers and sisters are in, and the one our Israeli brothers and sisters are in.

There’s one thing missing in this picture though, and that’s the way Passover connects us to the miraculous. Last Saturday’s thwarted Iranian attack was not quite the parting of the sea, but it was still miraculous. When we open the door for Elijah, let it help us keep the door open to the possibility of unexpected change. Let us remember that peace can come, that despair can be overcome, that human wickedness, greed and stupidity, has – incredibly - not completely undone us up to this point in history, and may yet be transformed.

This week’s Haftarah describes the type of reconciliation that Elijah’s return brings:

וְהֵשִׁ֤יב לֵב־אָבוֹת֙ עַל־בָּנִ֔ים וְלֵ֥ב בָּנִ֖ים עַל־אֲבוֹתָ֑ם

And the hearts of parents will turn back toward their children,

and the hearts of children toward their parents.

I leave you with one suggestion for a transformation of the text of one sction of the Haggadah that seems appropriate this year. Written by Elana Blum from the NYC Anti-Occupation Block, it suggests that something’s got to be different about this year’s Seder, maybe even radically so, but we have to build it on the Seder as we know it. Instead of the usual text about the four children, and how parents should deal with each type, we find the opposite. Maybe instead of parents teaching kids, this is the year that parents learn from their kids.

“The Four Parents”

by Elana Blum

With love to your people and mine / Passover 5784 (2024)

1. The wise parent says, ‘Here are all the laws which God commanded us to observe on Passover, and all the customs of the Seder. Come and study them with me.’ To this parent you shall say, ‘I will study our laws and customs with you, and I will also think about them in new ways.’ And you shall share your thoughts with them, even those they do not recognize, so they can see that you will treasure the legacy and make it yours.

2. The wicked parent says, ‘How dare you reject my tradition and my version of our history? You do not belong at my table.’ To this parent you shall say, ‘it is because you value me only as a reflection of yourself that I reject your teaching. I will read our story in my own way, and you will not be part of it.’

3. The simple parent says, ‘We are having a feast with matzo tonight! Eat, my child.’ You shall say to them, ‘I do not love matzo. But I learned that we eat it because our ancestors escaped from slavery, and I will tell you the story.’

4. As for the parent who does not know how to teach, you must begin for them, and explain: ‘This ritual belongs to us, and I will bear it forward.’

Wishing you a happy Passover, a Zissen Pesach and Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Point of Departure

by Rabbi Misha

The story of this war begins on October 7th, 2023. No, it begins several years earlier when Gaza was closed off. No, it begins in June 2007 when Hamas beat Fatah and took over the Strip.

Jacob as outer space Haman with the mask he made at Herbrew school

Dear friends,

The story of this war begins on October 7th, 2023. No, it begins several years earlier when Gaza was closed off. No, it begins in June 2007 when Hamas beat Fatah and took over the Strip. No, it begins on August 16th, 2005 when Israel pulled out of the Strip. No, it begins November 5th 1995 when Rabin was assassinated. No, it begins in 1967 when it was conquered. No, in 1948 when hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees arrived. No, in 1939 with Hitler. No, in 1897 in the First Zionist Congress. No, it really begins on October 8th, 2023.

Different ways of telling the story create vastly different stories, with incredibly different messaging, and very different realities. The point of departure is key, in both senses of the word “point.” At which point in time do you begin your telling, and what is the purpose of your story?

This is true for the war, and it is no less true for our national and religious stories.

In the last century BCE, our rabbis of blessed memory were tasked with framing the story of Hanukkah. The tale they had been handed down was one of victorious religious zealot-warriors. The nationalistic story of the Maccabees, the oppressed few who took up arms and beat the great Greek army was accompanied by violent acts of bigotry toward the less nationalistic Jews. The rabbis decided to completely transform the story. Theirs began at the end of the war, when the search for holy oil began at the temple. For hundreds of years the focus of the holiday was the miracle of the oil. It was only after the Holocaust when the Zionist movement brought the Macabbees back into the forefront, as a means of empowering a beaten down nation with the possibility of taking history into their own hands.

For the past three weeks I have been in the business of challenging the way we tell the Passover story. This weekend we are devoting two performances of Pharaoh to a discussion about how we tell our stories. Last night, in the talkback with Rabbis for Ceasefire, we examined the relationship between the way the Exodus story is told, and the story Jews tell about this current war.

Tomorrow night we will be joined by Professor Richard Schechner, a theater visionary who changed the way stories are told in the theater, by bringing a multi-cultural approach to the stage. In my “Intro to Theatre” class in undergrad I was taught about Schechner’s work on Rasa, an ancient Indian approach to emotion in performance, which offers an antithesis to the realistic acting style practiced in the west. The melding of ancient sensibilities with contemporary edge, which Schechner explored with The Performance Group, (later to become The Wooster Group) brought about an entire new field called Performance Studies. Schechner is considered the pioneer and leader of this influential movement.

When we seek other modes of storytelling, even for our own stories, we open ourselves to fresh thinking, and invite not only our familiar methods, but the universal mind that exists within each of us. The prophet Ezekiel promises us in this week’s haftarah that we will be offered “a new heart.” “I will remove from you the heart of stone, and will give in you a heart of flesh,” we are promised. May our stories, and the ways we tell them bring us closer to that reality.

I hope you can snag one of the few remaining tickets and join me tonight or Saturday at 8pm (with Prof. Schechner), or Sunday at 3pm for the final performances of Pharaoh.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Wear Your Enemy

by Rabbi Misha

In 1934, in the dead of winter, the chief rabbi of Palestine, Harav Kook received an urgent telegram. Three Jews escaping persecution were caught making their way through the snow from Russia across the Polish border. Their white clothes used for camouflage didn’t help.

Jacob as outer space Haman with the mask he made at Herbrew school

Dear friends,

In 1934, in the dead of winter, the chief rabbi of Palestine, Harav Kook received an urgent telegram. Three Jews escaping persecution were caught making their way through the snow from Russia across the Polish border. Their white clothes used for camouflage didn’t help. Now they were about to be handed over to the Russian authorities to suffer the penalty by Russian law for such a crime: death. The rabbi sprung into action, sent some urgent communications, and miraculously, managed to release the three and bring them to Palestine. They arrived 90 years ago today, on the eve of Purim, into a drunken celebration. When they recited: “cursed is Haman who tried to annihilate me,” they knew what they were talking about.

In the midst of the rejoicing the chief rabbi, born and raised in the Russian empire, did something unexpected. He began singing an old Russian soldier’s song. He danced and sang, and the entire community joined in on the song.

Now why would the rabbi bring such a strong representation of the enemy that almost killed three innocent Jews? And why would he get everyone present to sing and dance to it? Is this not the moment to celebrate the prisoners’ release, rather than reminding them of the songs of their captors?

The answer is no. It’s exactly the way Purim brings healing. The Holiday of Peace, as Rabbi Natan of Nemirov called it, is exactly the time to step into our enemies’ mindset, to explore our adversaries’ emotional world, to transform ourselves into those we disagree with in an overwhelming show of empathy. We dress in costume to get out of ourselves. We get drunk in order to allow a softening of the hard lines in our thinking. It is the only time of year when we are commanded to see something different in those we hate.

In wicked people there is a spark of goodness. In cruelty there are remnants of kindness. In Haman too there is god.

When we enter this mindset what we find is not agreement with those with whom we disagree, but a softer understanding for a day, a relaxing of the shoulders, a greater harmony in the world.

Many voices have called for a purim with no groggers this year. They see in it a representation of the vengeful mindlessness that is far too present in this war. Perhaps the noisemaking can be transformed as well, from a mocking cry of victory to a call to the spark in the soul of wickedness.

Tomorrow evening we will gather at the theater to watch Pharaoh, drink, munch and make merry. This play is an attempt to help us all wear Pharaoh, in order to increase empathy, soften our hard lines, and open a window to a more harmonious human kind. It has been wonderful witnessing both spectators and critics respond so powerfully to this message. I hope you can join us!

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Attention Is Love

by Rabbi Misha

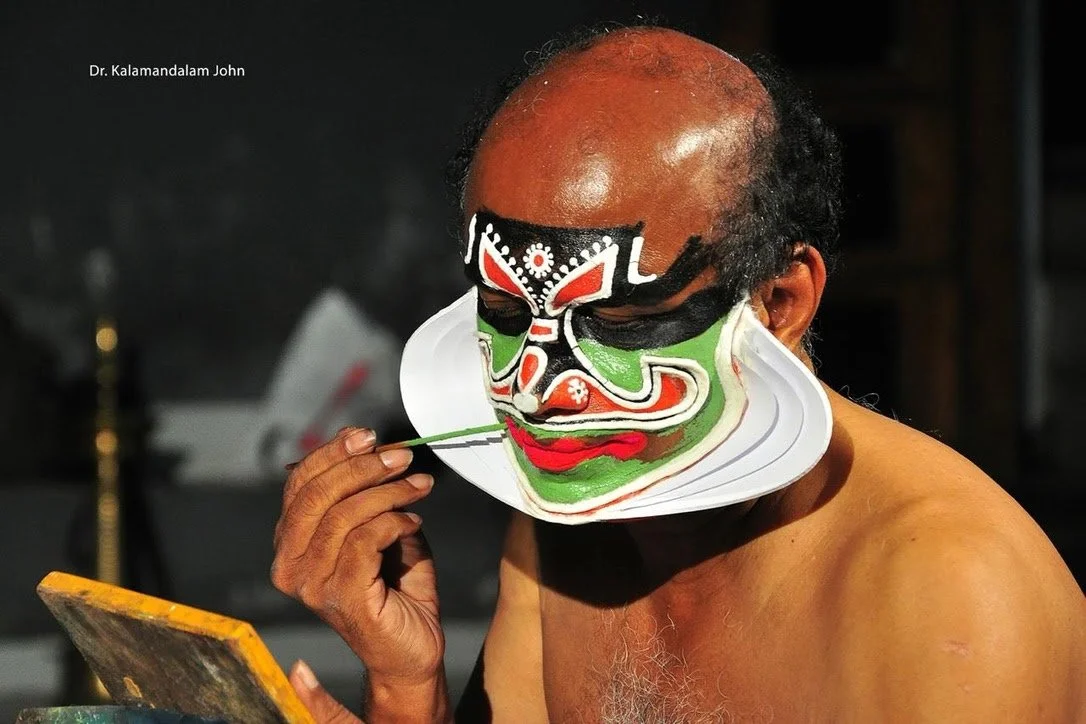

Last night we finally got to see John get made up and assisted into his costume. It’s a process that takes several hours.

Some of Kalamandalam John's Kathakali costume for Pharaoh, laid out in preparation to be worn, including the four-piece-crown.

Dear friends,

Last night we finally got to see John get made up and assisted into his costume. It’s a process that takes several hours. His wife, Marie, a Kathakali make-up artist, carefully applies the special dyes and powders onto his face in precise designs created hundreds of years ago. She paints his face red, green and white, and his forehead black. Then begins the process of putting on the costume. Piece by piece, in a particular order handed down through the generations, the forty pounds of dozens of costume pieces are attached. It begins with the bells on the legs and works its way all the way up to the crown of the head.

Each costume piece is made by a specialized artisan, using specific materials. Tremendous care is placed into every detail. The crown alone takes one month of work by a carpenter, and another month by a decorator. No one may wear shoes around the costumes. These are sacred garments. Without the right attitude, the ritual will not be fulfilled, the magic won’t happen.

Never before have I taken in this week’s parashah so clearly:

וּמִן־הַתְּכֵ֤לֶת וְהָֽאַרְגָּמָן֙ וְתוֹלַ֣עַת הַשָּׁנִ֔י עָשׂ֥וּ בִגְדֵי־שְׂרָ֖ד לְשָׁרֵ֣ת בַּקֹּ֑דֶשׁ וַֽיַּעֲשׂ֞וּ אֶת־בִּגְדֵ֤י הַקֹּ֙דֶשׁ֙ אֲשֶׁ֣ר לְאַהֲרֹ֔ן כַּאֲשֶׁ֛ר צִוָּ֥ה יְהֹוָ֖ה אֶת־מֹשֶֽׁה׃

וַיַּ֖עַשׂ אֶת־הָאֵפֹ֑ד זָהָ֗ב תְּכֵ֧לֶת וְאַרְגָּמָ֛ן וְתוֹלַ֥עַת שָׁנִ֖י וְשֵׁ֥שׁ מׇשְׁזָֽר׃ וַֽיְרַקְּע֞וּ אֶת־פַּחֵ֣י הַזָּהָב֮ וְקִצֵּ֣ץ פְּתִילִם֒ לַעֲשׂ֗וֹת בְּת֤וֹךְ הַתְּכֵ֙לֶת֙ וּבְת֣וֹךְ הָֽאַרְגָּמָ֔ן וּבְת֛וֹךְ תּוֹלַ֥עַת הַשָּׁנִ֖י וּבְת֣וֹךְ הַשֵּׁ֑שׁ מַעֲשֵׂ֖ה חֹשֵֽׁב׃

“Of the blue, purple, and crimson yarns they also made the service vestments for officiating in the sanctuary; they made Aaron’s sacral vestments—as יהוה had commanded Moses. The ephod was made of gold, blue, purple, and crimson yarns, and fine twisted linen. They hammered out sheets of gold and cut threads to be worked into designs among the blue, the purple, and the crimson yarns, and the fine linen.”

This is just a brief segment from the Torah’s careful description of the priest’s clothes, which is imbued with that very sense of specificity and attention to detail that we witness in John’s costume. Theater, we are reminded, is ritual. Religion, we are reminded, is theater.

One of the thin threads connecting the two is the loving attention we pay to performing these rituals as they should be done. Why? For the sake of the ritual.

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve performed plays that I’ve worked on for months in front of a handful of people, for little to no money, without more than a few clapping hands in return. Traditional all night Kathakali performances are usually watched by small audiences, often comprised of Kathakali students. They do it for the sake of doing it. Lishma, as the Jewish tradition calls it, for its own sake. This is the secret. When a human goal is removed from what we do, we can pay very close attention to it, and that in itself is peace. We suddenly find ourselves in love. In other words, attention is love.

If you haven’t noticed yet, I’m eager to share my play, Pharaoh with you all. I hope you can come see it sometime between this evening when we open, with the grace of God, and March 31st when we close. John has invited those who would like to see it, to come watch some of the process of putting on his make-up and costume. Make up will begin around two and a half hours before showtime. Shoot me an email if you plan on coming to see it.

And for those of you staying home tonight, please join the virtual Shabbat that Rabbi Abby will be leading this evening.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Religion in Technicolor

by Rabbi Misha

Every spring, exactly one week before Passover a unique ritual takes place in the South of India. The local Jews leave their towns, cities and villages, and make pilgrimage to a small, holy mountain tucked away to the east of the backwaters.

A different kind of holiday celebration at the School for Creative Judaism

Dear friends,

Every spring, exactly one week before Passover a unique ritual takes place in the South of India. The local Jews leave their towns, cities and villages, and make pilgrimage to a small, holy mountain tucked away to the east of the backwaters. As the sun sets, they climb the 1800 steps that lead up to the mountaintop shrine, where they gather to watch the play that they have seen every year since their birth. It depicts the Pharaoh of Egypt’s struggle to understand how he brought about the death of his first-born son in the tenth plague.

After lighting the ritual flames, they watch him tell the story we all know of the Hebrew slaves’ leader Moses, and the ten plagues he brought upon Egypt in order to secure their release from slavery. They hear Pharaoh’s reasoning for refusing to let the Hebrews go and watch him turn from an all-powerful god-king to a sad, broken father. And then they walk down the mountain singing a psalm of humility.

They have felt the pain of their enemies. They have witnessed the consequences of their fight for freedom. They have internalized their adversary’s perspective. They have shed a layer of certainty and gained a layer of understanding.

Now they are ready to celebrate Passover.

There is no lost Jewish tribe of South India that performs this ritual. I made it up when I sat down this week to write my playwright's note for my play, PHARAOH. But what if there were such a tribe with that ritual? What if this were a tradition right here in New York City, which would take place at the highest point in Fort Tryon Park, or on Mount Prospect Park, or up the river over the Hudson? How would it change our experience of Passover? Our relationship with liberation? What would the inclusion of a ritual play in our religious practices do to our experience of our faith tradition? What would preparing for Passover by diving into the inner world of Pharaoh do to our national psyche and our political behavior in the world?

It has always seemed to me, and I’m oversimplifying here, that Jews have a hard time imagining the Palestinian experience. “There is no Palestinian people,” they would tell me as a kid, even as I would see people hanging up a Palestinian flag on the lamppost beyond the fence of my elementary school in Jerusalem. I was never taught anything about the history and culture of those we shared the land with. They were often represented simply as terrorists. There was an incredible flattening of the humanity and the culture of our neighbors.

The story of the telling of the exodus is not dissimilar. We grow up with a stick figure cruel king who kept saying "No, no, no," for no reason whenever the Hebrew freedom fighter would ask him to let the slaves go. That's not far from how the Haggadah tells it too.

The Torah, however gives a richer depiction of Pharaoh. in several interactions he listens quite carefully to Moses, and makes him offers that seem like they should satisfy his requests. "חטאתי ליהוה," the king even says to Moses a few plagues in, "I have sinned to YHVH." Is that not at least the beginning of a repentance process?

Furthermore, the king of Egypt offers perhaps the thorniest problem regarding free will in the entire Torah. Over and over again we are told that "YHVH hardened Pharaoh's heart." It appears so many times that the commentators have to excuse this breach of human freedom - upon which the entire belief system is founded! - with the excuse that God only hardened Pharaoh's already hard heart. Not only is this a weak excuse, but it also negates a prime principle of rabbinic biblical exegesis, that every word in the Torah is exactly right, and holds both straightforward and deeper meanings. The matter serves to further enrich the king's character, who appears to be moved to denying the Hebrew's demands by God, rather than his own impulse.

The Torah, in other words, offers us a nuanced character, Since then, this biblical character has been systematically flattened into the one that appears in our children's songs, out of a human desire for simplicity. We seem to be wired to need black and white in order to function. But that is precisely what creates a colorless reality.

PHARAOH, which opens a week from today was the play I wrote as my main project toward becoming a rabbi. I wrote it as a rejection of the black and white that led us to October 7th, as well as October 8th through today; a rejection of the knee-jerk vilification of those we disagree with; and an invitation to recreate our ancient faith traditions as complex, forward-looking frames, through which we can see all the colors of the rainbow.

I hope you can join us this evening for a colorful New Shul Shabbat of Peace, which will include an array of incredibly talented Broadway singers and musicians, freedom songs by the inimitable Rob Kaufelt and prayers for a better world.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

One (and only?)

by Rabbi Misha

Before I begin, I'd like to invite you all to a very special gathering we're holding this evening, which can connect us to both the reality of the current situation in Israel/Palestine, and the hopeful ways people are working to overcome it.

Kalamandalam John

Dear friends,

Before I begin, I'd like to invite you all to a very special gathering we're holding this evening, which can connect us to both the reality of the current situation in Israel/Palestine, and the hopeful ways people are working to overcome it. Spirit of the Galilee is an important organization working on co-existence between different faiths and cultural groups in the north of Israel. We will be joined by Ghadir Haney, a renowned and highly influential Muslim social activist, from the city of Acre, Fr. Saba Haj, the leader of a 5,000-member Christian-Arab-Orthodox Church in the town of Iblin, and Rabbi Or Zohar, Reform Rabbi of the Misgav region and director of the Spirit of the Galilee Association (SOG). These are critical voices for us to hear and take in here in the US, and I hope you can all join in person or tune in.

And now I'll pick it up from where I left off last week.

When he was fifteen years old, John was living a perfectly normal life for a Christian teenager in the South Indian state of Kerala. He went to the local school, and to the nearby Orthodox church for religious instruction . And then something happened that radically changed his life. He went to the theater.

Kerala is home to two of the oldest existing theatrical traditions in the world, which are kept as national treasures, but watched by very small audiences. Kudiyatam is the slower and more drama oriented form, in which a play lasts between 9 and 43 nights, each night between 2-5 hours. Kathakali is a form of dance theater with a faster pace, resulting in plays that only last one full night. At fifteen, John witnessed the latter and immediately fell in love. It did not matter to him that Kathakali tells only the stories of the Hindu gods from the great epics, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. Nor did it matter that most performances took place in Hindu temples, and included the actors paying obeisance to the temple gods. John left his school and his church education and devoted himself entirely to becoming a Kathakali actor.

For 9 years he studied the ins and outs of the form, at the prime school for Kathakali, the Kerala Kalamandalam. The full day, physically demanding days teach the actors techniques of controlling each part of their bodies, from head to toe. Mornings begin with eye exercises, continue with the study of abhinaya, the unique sign language used in Kathakali and Kudiyatam, and end with rigorous dancing. When he graduated, John was awarded an excellence award, and became the world’s first ever Christian Kathakali actor, and was awarded the honorific Kalamandalam John.He performed the Hindu plays for many years. When the opportunity presented itself he created a Kathakali play about the Christian saint who first came to the region from Syria. Despite controversy, he performed the saint without the elaborate make up and costume, in a simple monk’s outfit.

His wife Marie also shook things up in the Kathakali world, when she learned the art of Kathakali make up and began to prepare John for performances, (as you can see in the picture above) a process which takes three hours. She is the first and only Indian woman Kathakali make up artist.

John exhibits two things that impress me deeply, beyond the incredible talent and knowledge that come with 50 years of performing and teaching Kathakali. The first is a rare openness to experimentation and new creations, which remains rooted in this ancient theatrical form. And the other is the deep-seated openness around divinity that I have only witnessed in India. How could a devout Christian pay obeisance to Siva, Rama, Brahma, Vishnu or any of the other Hindu gods? How could he participate in a play written by a rabbi who considers the performance an offering to God? Because God is one.

The old Indian way is welcoming and inclusive of any and all gods. “Who, Jesus? Sure! Bring him into the temple! Adonai you said? An invisible god? Great, let’s put one of his symbols next to Ganesh.” This welcoming multiplicity comes from a deep understanding that God is simultaneously the most serious business we have, and a manifestation of human play. It’s so real that it goes beyond the categories we habitually use for reality. Using God to exclude or denigrate others is the ugliest type of idol worship.

My play, Pharaoh is in part an attempt to define what we mean by the phrase “one god.”

“What does it mean when you say ‘one and only God,’” Pharaoh asks Moses in one scene. After Moses scoffs at the question Pharaoh digs further: "So you're saying that everything we Egyptians believe in is a......"

"Fantasy," Moses answers.

This absurdly vain idea, that my imagining of God negates yours, has been bugging me since the first time I ever stepped into a Hindu temple, and was slapped with my people's centuries of guilt and prohibitions. I was sixteen and vulnerable to such guilt trips. And yet I quickly began to see how that exclusionary vision is being used not only for religious and cultural reasons, but for political purposes, with dire consequences.

Both monotheistic and polytheistic traditions can be either inclusive or exclusive, depending on your interpretation of the core idea of godliness in them. The current Indian government is taking an inclusive and playful faith tradition, and twisting it to exclude and humiliate Muslims and other faiths. Some Christians, Muslims and Jews around the world sin by interpreting the notion of one god as an exclusive and punishing “truth.” The faith I live by is a monotheism that is not threatened by other gods or notions of divinity, but raised up and buoyed by them. “Adonai Echad,” "God is one," means we are all one, a part of the all. The idea that “only my god is real” is, to my mind the opposite of the Torah’s charge.

Today, when John inhabits a character, he is in a glorious and unified command of his body. A decade of rigorous training followed by four decades of performing and teaching all over the world manifest in the spectator’s sense of watching a master at work. Countless times in rehearsal, Michael, Alysia and me have been swept into wonder watching John bring Pharaoh to life through movement.

Let us all take a page from Dr. Kalamandalam John in bringing true glory to God, through the open creativity, playfulness and inclusive understanding of the concept of God, and its expression through the wonder of the human body.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Pharaoh Sends Love

by Rabbi Misha

It has been fifteen years since I began obsessing over Pharaoh. It began in a tiny village in the south of India, a lush, tropical heaven by a river, where I had come to watch a play. It was a little longer than most plays I had seen with a run time of just over two weeks.

Chakyar Margi Mahdu as Ravana in the Asokavanikangam. Photo by Ranjith S

Dear friends,

It has been fifteen years since I began obsessing over Pharaoh. It began in a tiny village in the south of India, a lush, tropical heaven by a river, where I had come to watch a play. It was a little longer than most plays I had seen with a run time of just over two weeks. Every evening we would gather at the Kuttambalam, a small, roofed open air theater a couple minutes walk from the temple. The drummers would take their seat atop the giant mizhavu drums, a conch horn was blown, and the actor would appear onstage, in the elaborate costume and make up of the ten-headed demon king, Ravana. That is when the improvisation would begin. Using the unique sign language of the Kudiyatam theatrical tradition, he would remind us what happened yesterday, and then enact for us the next piece of the story, complete with hours-long diversions to paint the full picture of the associations and memories the story evokes in Ravana’s gorgeous mind. It might go on four hours. Usually a bit less, sometimes more.

The play was called the Asokavanikangam, or Asoka Tree Garden, and told of the time when Ravana kidnapped the goddess Sita, wife of Rama, and did everything he could think of to convince her to sleep with him. It didn’t work. Ravana was thrown into a crisis. Never before had he been prevented from accomplishing a task, fulfilling a desire. Several times during the course of the play he recalls the time when his charioteer told him they would have to travel around Mount Everest (called Kailasa in the play), because it’s too high to go over. Ravana refused to accept this indignity. He steps off the chariot, and though it might take him half an hour of stage time he eventually succeeds in picking up the mountain and moving it aside (not before some agile juggling). Now, however, he is faced with an obstacle he cannot surpass, in the form of Sita’s pure devotion to her husband.

Over the fifteen nights of the play we watched Ravana lose his powerful, charismatic self to the experience of limitation. While he would sit sadly on the floor reckoning with his inability and his tremendous lust, the theater would be visited by fruit bats, who would fly in and flatten themselves against the ripening bananas decorating each side of the stage.

This is what religion is meant to be. An encounter with human creativity, with joint brokenness, with the interconnected depths of good and evil, with the inconceivable beauty of life.

I came out of that experience with two convictions, one conscious and the other not yet. Consciously I decided to write a play that would offer the gift of falling in love with a mythical villain to a Western audience. A few days later I landed on the great enemy of the Hebrews, symbol of ego, stubbornness and cruelty to all three major monotheistic faiths, Pharaoh. The next day I arrived at the central temple of the great ancient Tamil city of Tanjavur. After offering gifts and prayers to the god Siva and his bull Nandi, I parked myself with a notebook in a corner of the temple, and out came the first scene, where Pharaoh battles Death, and wins.

Since then I have been spending far too much time with my beloved Pharaoh. I have learned of his genius, his relationships with his wife, daughter and son, his blind spots and his prophetic wisdom. I gained insight into the theological-political duel between him and Moses. I have come to see the destructiveness in the flat story of good and evil that our tradition attempts to maintain. And I’ve encountered through him my own hints of divinity, and my deep, human limitations.

After a path I could have never imagined, the play is set to open in a few weeks, with a South Indian master of Kathakali - the faster paced dance theater sibling of Kudiyatam - in the lead role, who will be dressed in the same costume and make up as Ravana was in that play I saw all those years ago. I’ll tell you more about this incredible actor and maybe more about the theological battle at the heart of the play in the coming weeks. And hopefully about that unconscious conviction I mentioned earlier as well. It’s rare for a playwright to have an opportunity to lay out the story of writing the play, and the ideas they are working out in them. I’m excited to take these next few weeks until the opening to dig into some of the driving questions behind my rabbinical and theatrical path, as they found expression in the writing, acting and production of Pharaoh.

For now I wish you a peaceful Shabbat. Pharaoh sends his love. Might it be time to open your heart to him?

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

The Angel in Your Dream

by Rabbi Misha

One of the greatest polemical books in the Jewish canon is The Kuzari, a medieval book by Rabbi Yehudah Halevi. The book tells of the idol-worshipping King of Kuzar, who has a recurring dream, in which he is visited by an angel who tells him:

Dear friends,

One of the greatest polemical books in the Jewish canon is The Kuzari, a medieval book by Rabbi Yehudah Halevi. The book tells of the idol-worshipping King of Kuzar, who has a recurring dream, in which he is visited by an angel who tells him:

כוונתך רצויה אך מעשך אינו רצוי

Your intentions are desired, but your actions are not desired.

The king understands that God is both pleased and displeased with him. He must keep his intentions of serving God, but change the ways in which he does it. The king then engages in philosophical, religious and theological conversations with a philosopher, a priest, an Imam and a rabbi, in an attempt to figure out which practice he should adopt.

At the heart of the book is a challenge to us all: can we ask ourselves the question posed by the angel. Where are our intentions good, but our actions not?

The question seems to me the stuff of dreams. Something that can gnaw at our subconscious at night and unnerve our days. But there have been times in my life, in which I've managed to locate a discrepancy between action and intention, moments in which I was telling myself I am doing one thing, but in effect doing another. During those times it is as if my body is serving someone else. And perhaps the strangest thing about it is that while it does that, buried in the back of my own mind is the full knowledge that this is taking place; that I am setting aside the connection between my mind and my body for a time, and living with the pain of that split.

Last week I related some of my military service, and several of you expressed interest in that experience. In my own limited conscious understanding of my self, there is no other experience I've been through that better embodies the angel's axiom about intention and action. The intention was to give back to the collective, to do my part, to protect life, to participate in the shaping of our world. The action was to uphold an occupation of a militaristic nation state.

People really do want to do good. I believe that about almost every person. I believe that about myself, and I believe that about you. But I know that our actions don't always result in goodness. The angel asks: Where are we not acting out our true selves? Where are our intentions taken hostage by someone else's agenda? Where are we supporting causes and projects that bring about our internal corruption or our national combustion? Where are we living someone else's life?

If we can find those places we might be able to unclog the channels between our pure intentions and our misguided actions.

If we can pose these questions to our waking, and more importantly perhaps to our dreaming selves, maybe we will be able to enjoy the deep satisfaction of having both our intentions and our actions desired by that mysterious force who keeps consciousness flowing.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Happiness in Tough Times

by Rabbi Misha

I always remembered my time in the Israeli army as depressing.

Living Theatre legend, Tom Walker, who died last week, performing a strike-support play with the company in Italy, 1976

Dear friends,

I always remembered my time in the Israeli army as depressing. Beyond the fact that soldiers are constantly counting backwards the days until they go home, and until their final release, I felt my time in the South of Lebanon as a moral compromise about which I was deeply conflicted. The idea of being a part of any army felt antithetical to who I am. And following the orders of the terrible and cruel man at the top of the pyramid – then first term Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu - didn’t help. Imagine holding a rifle that you have to shoot whenever the leader you hate most says shoot and you’ll understand the situation I was in.

Soldiers were dying around me, while rockets kept flying into northern Israel, the stated reason for our presence there. More depressing was the state of the local population, with which I had significant contact, since my base in Marj Ayoun served as the regional headquarters of both the IDF and the South Lebanon Army, a kind of puppet army of Israel. The locals had no prospects, between the allegiance they had to show the IDF to survive, and the knowledge that one day the Israelis will leave, and Hezbollah will take over and accuse them of collaboration with the enemy. I left in 1999, and indeed a year later that’s exactly what happened.

A few years after I was released, I visited my commanding officer, long out of the army, and like me pursuing a career in theater. Sitting in his apartment in Jerusalem, he showed me a photo from our service. Five of us were in his office in our uniforms, each of us with smiles on our faces. Mine was the biggest smile in the photo. The photo rattled me. It brought back the experience of the day to day there, the friends I hung out with, the exciting sense of moving around, hitchhiking up to the northern border, bussing down to see my girlfriend in her kibbutz near Haifa, reading Hemingway under the sole fig tree in the base, drinking Lebanese black coffee (rivaled only by Italian espresso in Italy) as I gaze out at the high mountains leading up to Syria in the east, and the Beaufort, a majestic Crusader fort above the Litani Valley to the west. That single photo shattered my conception of my time in the army. I saw it and knew that even within the painful circumstances, I had plenty of moments of happiness and contentment.

I find myself wandering back to that time in search of ways to be content during this period. The war rages on. The insanity of the death toll and the destruction of Gaza weighs heavy. The hostages that are still alive are not back. And that’s before I even go into my more mundane anxieties and painful events here in New York. Anyways this stage of winter has a way of getting me down.

And yet – this evening begins a new moon.

This moon of the Hebrew month of Adar brings with it a command:

משנכנס אדר מרבין בשמחה,

“Once Adar begins, we do lots of happy.”

More than that, this is a leap year in the Hebrew calendar, which means we get two months of Adar. Do you feel that kick in your ass to step out of your malaise? Those are your ancestors saying “snap out of it! Life is short.” It’s time for us to actively seek happiness, relaxation, peace. We deserve it.

Shortly after I came out of the army and engulfed myself in the New York downtown arts scene, I met a theater troupe that had just come back from a series of workshops in Lebanon. When they were down south, in what was by then Hezbollah territory, they created an anti-war play in the notorious Al Hayyam prison, where the IDF would imprison and often torture suspects. Led by the daughter of a rabbi, The Living Theatre is a pacifist-anarchist group that was in the business of taking the brokenness of the world and the pain in their souls and transforming it into borderless, theatrical love. My years with the company taught me a lesson about joy: it’s not about ignoring pain; it’s not about ignoring the world; it’s not about ignoring what you feel commanded to do. Be with it, and see through it into God, into humanity, into the dancing soul of the universe.

I hope you can all join us this evening for Shabbat, where we will follow the tradition of finding joy on the narrow bridge. John Murchison, a wonderful Qanun player will be joining Yonatan and Daphna in bringing the music, and rabbi and activist Miriam Grossman will join me in laying out the ideas that might lead us to finding happiness and peace.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Nothing on My Tongue

by Rabbi Misha

Imagine the world going silent.

Dear friends,

Imagine the world going silent.

Perhaps the last time such a moment took place was 3,334 years ago (according to Rabbinic calculations.) That was when our people stood at the foot of Mount Sinai, as described in this week’s parashah, and expounded upon ever since.

“When the Holy Blessed One gave the Torah no songbird chirped, no winged creature took flight, no cow mood, no angel flew, no seraph said “holy!” The sea did not move, the people did not speak, but the world is quietly keeping silent – and the voice came out: “I am YHVH your God.”

Without keeping silent, we learn, revelation would not have come. Keeping silent is an old virtue that could use some reviving. So much of our anguish and anger these days come from people's inability to measure their words.

“Rabban Shimon Ben Gamliel said: All my days I grew up among the sages, and I did not find anything as good for the body as silence: and anyone who speaks too much brings about sin.”

The silence that took over the world before the utterance of the first of the Ten Commandments (or in Hebrew the Ten Dibrot, or spoken pronouncements), allowed for the word of God to be heard in all of its precision and power. It imbued the words that came out with a transcendence of time and space.

The rabbis succumb to their poetic instincts:

“Every single word that came out of the mouth of the Holy Blessed One filled the entire world with the smell of sweet spices.”

“Every single word that came out of the mouth of the Holy Blessed One split into seventy languages.”

“When the Holy Blessed One gave the Torah to Israel His voice went from one end of the world to the other, and the kings of all the nations were taken over by trembling, and they began to sing.”

And yet, precise words that come after true silence can be dangerously strong.

“Every single word that came out of the mouth of the Holy Blessed One made the souls of Israel depart.”

In other words, when the Hebrews heard God’s voice, they all died! Then how did we receive this story, you might ask.

“The word came back in front of the Holy Blessed One and said: Master of the world, you’re alive and your Torah is alive – but you sent me to dead people?! - They’re all dead!

The angels began to hug and kiss them. “Don’t worry, you are children of YHVH!” And the Holy Blessed One sweetened the word in His mouth and said to them: are you not my children? I love you! And continued to touch them until their souls returned.”

That word travelled all the way to the end of the world and right up to its source.

This is the power of a word preceded by silence. Not only can it kill, but it can also give life, as the Book of Proverbs put it:

מוות וחיים ביד הלשון

“Death and life are in the hand of the tongue.”

At our Kabbalat Shabbat next Friday we will be transported by the Qanun of our musical guest, John Murchison to that prayerful realm of “nothing on my tongue but Hallelujah,” as Leonard Cohen described it. Until then, let us all practice staying silent, and maybe allowing the few precise words that follow to emerge.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

A Happy Story

by Rabbi Misha

A happy story is set to reach its climax tonight in my neighborhood in Brooklyn. You’re all invited, and it’s worth accepting and taking the Q train out to Cortelyou Road to witness it tonight at 9pm.

Tu Bishvat Seder this week in our Windsor Terrace branch of the School for Creative Judaism

Dear friends,

A happy story is set to reach its climax tonight in my neighborhood in Brooklyn. You’re all invited, and it’s worth accepting and taking the Q train out to Cortelyou Road to witness it tonight at 9pm.

It started, like many stories begin these days, with anger and accusations of hate, followed by cancellations. But then, right as everyone was taking sides and feeling hurt and commenting and grieving how rotten the world has become, there was an unexpected twist in the plot. It was so radical that it disarmed all the nay sayers and confused all the yay sayers and reshuffled the deck to shake it out of the political, and into that distant realm we used to occasionally inhabit called “human.”

The story began when a Palestinian restaurant opened a couple months ago. The owner, Abdul Elenani, an Egyptian married to a Palestinian woman, named the restaurant after his beloved, Ayat. There were several bold decisions made by the owners. When you walk in the first thing you see is a large mural of Al Aqsa. Around it are images of beauty, and oppression. When you open the menu the first thing you see is a full page in Arabic, Hebrew and English that reads: “End the Occupation.” All of that did not cause a stir. What did was the seafood section. It reads: “From the River to the Sea: Shrimp Kebab, Salmon Kebab, Whole Red Snapper, Whole Branzino.”

Within a few weeks from opening, Abdul had received dozens of hate mail, death threats and suggestions for what should happen to the dead and living of the Gaza strip. Soon after, newspapers began reporting about it. Some Jews in this incredibly diverse neighborhood swore it off, while others started organizing a boycott.

And then Abdul miraculously transformed the direction of the story. There were also Jews who came to the restaurant to show solidarity in the face of the boycott. In conversations with them he managed to come up with a plan: he invited them, and the entire Jewish community of the neighborhood to a Shabbat dinner. Word started trickling out. I caught word of it on the Whatsapp group of Israeli peace activists in New York, after one of the members received a warm invitation from Abdul, telling him to bring all his Israeli friends. “Everyone is welcome.” Under current circumstances Palestinians inviting Israelis, no matter how left wing they are, is almost unheard of. Abdul made it clear that the dinner will be free. He hired musicians to make the event festive. And Kosher caterers to allow for all Jewish diets to attend.

When we started realizing how big this event is becoming, some of the Israelis organized a second dinner, for the activists, who wanted to pay for their dinner. Abdul tried to convince us not to pay, but eventually agreed for people to pay whatever they felt comfortable paying. This past Monday 50 Israelis gathered at Ayat for dinner. It was a rare moment for a community of dispersed and argumentative peace activists - as marginalized as anyone these days - to come together and share a happy moment. Many of us will be there tonight again.

The title of the seafood section remains the same. But the understanding of the phrase, when sitting in the restaurant (which has a few other branches around the city) is different. This was the brilliance of Abdul. He told the NY Post: “You can’t come to me and translate my verse. You should ask me and I will give you my translation. I’m not going to change it because you want to change the meaning to feed your story.”

What does it mean to him? “This mantra stands for Palestinians to have equal rights and freedoms in their own country. In no way does this advocate any kind of violence.”

Personally, I’ve heard this mantra many times in my life. I don’t like it when Palestinians use it, or when Jews use it. But there was one time when for a moment it sounded just right, when my friend, activist and writer Udi Aloni roared it at a protest: “From the river to the sea ALL the people will be free!”

I am of course aware of the problematic nature of this phrase, and of the erasure it implies in the minds of many people who employ it. But the simplicity, even the innocence that it can hold when spoken by some, helps me in those cases to remove the armor, the tinted glasses, and whatever is on my ears skewing the sound bites, and see a human being. This is what can save us. This is redemption.

If one man can take a cancellation circus and transform it into a celebration of humanity, maybe a lot more of the horrors we are witnessing are also opportunities for transformation.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Wonder, Mindlessness and A Love Supreme

by Rabbi Misha

Creation is the move from chaos to order that is often obscured by darkness. Like most things in this universe, we can’t see it happening. It’s like the communication between trees, the realization reached by the person next to us on the subway, or the perfect, disjointed unison of a Jazz quartet.

John Coltrane - A Love Supreme, Part IV - Psalm (Live In Seattle, 1965)

Dear friends,

Creation is the move from chaos to order that is often obscured by darkness. Like most things in this universe, we can’t see it happening. It’s like the communication between trees, the realization reached by the person next to us on the subway, or the perfect, disjointed unison of a Jazz quartet.

“I never have to tell them anything,” said John Coltrane of his three collaborators, McCoy Tyner, Jimmy Garrison and Elvin Jones shortly after they completed one of the greatest Jazz albums in history, A Love Supreme. “They always know what they’re supposed to do and are constantly inspired. I know that I can always count on them. And that gives me confidence. There is a perfect musical communion between us that doesn’t take human values into account.”

So goes creation. No human values. A logic far deeper is at play when, for example a seed sprouts in the earth.

“Even in the case of A Love Supreme," continued Coltrane, "without discussion, I don’t go any further than to set the layout of the work.“

Not to compare a professed servant of God to God, but it seems that Coltrane followed in the image of the divine, as described in Genesis:

“And the earth was formless and empty

and darkness was over the surface of the deep,

and the spirit of God was hovering over the waters.

And God said ‘Let there be light,’

and there was light.”

The holy phrase תהו ובהו, translated above as “formless and empty” is worth pausing over in this musical context. While the phrase is not exactly logical, more linguistic or poetic, possibly even onomatopoeiac, תהו comes from תהה meaning to wonder, and בהו from בהה meaning to mindlessly stare, or zone out. The chaotic raw materials of creation are mindfulness and mindlessness. These are often the two elements that lead to something new. The wondering, a type of thinking that implies curiosity and inquiry is the active element. And the blank staring is a type of passive emptiness without which, in my own experience new ideas don’t come. We need both the search and the rest, the waking and the sleep for newness to appear.

Consider this statement from Coltrane: “For me, when I go from a calm moment to extreme tension, it’s only the emotional factors that drive me, to the exclusion of all musical considerations.”

What rises in him while he’s blowing his horn is divorced from the musical structure of the piece. The moment of creation, as we might call it, when a musician is truly connected, and allows their instrument to be a vessel of the soul, is a moment of chaos and freedom, which can only come about within the structure held by the other members of the ensemble. While he’s in תהו, wonder, the rest of the quartet is in בהו, mindlessness. When they hold the wonder - he can inhabit the emptiness.

With the frame of melody, chord progression and improvisation, Jazz combines structure and freedom, intention and emptiness, prayer and meditation. This is especially true of the Spiritual Jazz out of which was born A Love Supreme, a blast of inspiration shot into the world in 1964, from a musician who called music his “way of giving Thanks to God.”

Tonight we will be gathering at the National Jazz Museum in Harlem to experience the overlap between music and faith that drove Coltrane, through the Jewish Jazz of our musical guru Frank London, and his ensemble. I hope to see you there.

We see the chaos in the world. We tremble at its empty formlessness. What we cannot yet see is the new light being created out of it. Perhaps we will catch a glimpse of it this evening.

There is a structure to the universe. Some have heard it called a love supreme.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Out of the Depths

by Rabbi Misha

To mark 100 days of the hostages in captivity, and 100 days of death and destruction, as a means of praying for an immediate ceasefire, an end to the displacement, destruction and killing of innocents, and a safe return of the hostages, I turn to the ancient words of the poet:

Gaza, as seen from Kfar Aza. Photo by Itamar Dotan Katz

Dear friends,

Dear friends,

To mark 100 days of the hostages in captivity, and 100 days of death and destruction, as a means of praying for an immediate ceasefire, an end to the displacement, destruction and killing of innocents, and a safe return of the hostages, I turn to the ancient words of the poet:

מִמַּעֲמַקִּים קְרָאתִיךָ יהוה

Out of the depths I call to You

Two great minds help me make meaning of these words and those that follow in Psalm 130. 19th century German rabbi, Samson Rafael Hirsch, and contemporary (Jewish) Zen priest and translator of the Psalms, Norman Fischer. This psalm, writes Rabbi Hirsch “sings of the ways in which the Jewish spirit can rise up even from the depth of that deepest misery of all, misfortune coupled with the burden of guilt.”

This is our situation, after being brutally attacked, and having responded with an operation that took the lives of at least 23,357 people.

The poet continues:

אֲדֹנָי שִׁמְעָה בְקוֹלִי תִּהְיֶינָה אָזְנֶיךָ קַשֻּׁבוֹת לְקוֹל תַּחֲנוּנָי:

Listen to my voice

Be attentive to my supplicating voice

קוֹל תַּחֲנוּנָי, “My supplicating voice,” is not only about begging according to Hirsch. Coming from the Hebrew word חן, grace, it is the expression of a broken person’s commitment to improve: “I endeavor to make myself worthy of Your grace once more,” he translates. God hears our prayers when they are not complaints. The cries of help heard by divine ears are those in which despite our misery and despair we leave an opening to the possibility of human agency and goodness.

אִם עֲוֺנוֹת תִּשְׁמָר יָהּ אֲדֹנָי מִי יַעֲמֹד: כִּי עִמְּךָ הַסְּלִיחָה לְמַעַן תִּוָּרֵא

If you tallied errors

Who would survive the count?

But you forgive, you forbear everything

And this is the wonder and the dread

The dread is related to what Hirsch calls “the iron law of cause and effect.” We know what killing thousands children will do as well as Hamas knew what killing, kidnapping and raping brings. It should fill us with dread to the brim. But the wonder is there too in the form of the unknown, of the possibility of transformation, of the very real existence of changing one’s ways. In Hirsch’s words: “You have provided man, Your creature who is capable of sin, with the ability to rise up again at any time, and assured him of Your help and forgiveness in his striving for redemption from the bondage of sin.” There is both wonder and dread in the idea of forgiveness, in which in Hirsch’s understanding the past is wiped out, and instead we might experience “a new future, untouched by all the consequences of previous error.”

קִוִּיתִי יהוה קִוְּתָה נַפְשִׁי וְלִדְבָרוֹ הוֹחָלְתִּי: נַפְשִׁי לַאדֹנָי מִשֹּׁמְרִים לַבֹּקֶר שֹׁמְרִים לַבֹּקֶר

You are my heart’s hope, my daily hope

And my ears long to hear your words

My heart waits quiet in hope for you

More than they who watch for sunrise

Hope for a new morning

“Together with the awareness of my guilt,” Hirsch explains, “there is also the hope and trust in forgiveness.” It is hard to see forgiveness now, but we know it exists, and can appear unexpectedly as it has done countless times in each of our lives. “Even in the low state to which I have descended through my own fault, within the inalienable core of my soul there lies the force that will draw me up... a force which, in the midst of the night of my own life and from the darkness of the nights of time, will help me find the light that heralds its approaching nearness. And my own trust in the morning to be brought to pass by the coming of forgiveness is greater and surer still than that of the eye which looks eastward at night to watch for the morning.”

יַחֵל יִשְׂרָאֵל אֶל יהוה כִּי עִם יהוה הַחֶסֶד וְהַרְבֵּה עִמּוֹ פְדוּת: וְהוּא יִפְדֶּה אֶת יִשְׂרָאֵל מִכֹּל עֲוֺנֹתָיו

Let those who question and struggle

Wait quiet like this for you

For with you there is durable kindess

And wholeness in abundance

And you will loose all our bindings

Surely

The word "Yisrael" means those who question and struggle. What allows us strugglers to find peace even in our darkest, most guilt-ridden hours is the knowledge that love is ever-available. Or in Hirsch’s words: “Loving-kindness is ready at all times to redeem.”

Here's Fischer's full translation:

Out of the depths I call to You

Listen to my voice

Be attentive to my supplicating voice

If you tallied errors

Who would survive the count?

But you forgive, you forbear everything

And this is the wonder and the dread

You are my heart’s hope, my daily hope

And my ears long to hear your words

My heart waits quiet in hope for you

More than they who watch for sunrise

Hope for a new morning

Let those who question and struggle

Wait quiet like this for you

For with you there is durable kindess

And wholeness in abundance

And you will loose all our bindings

Surely

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Dying With A Kiss

by Rabbi Misha

Moses died differently. So did Miriam and Aaron, as well as Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. These six all died, according to the Talmud, with a kiss from the shechinah, the gentle presence of God.

Dear friends,

Moses died differently. So did Miriam and Aaron, as well as Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. These six all died, according to the Talmud, with a kiss from the shechinah, the gentle presence of God. Some of us are lucky enough to receive a soft departure, and some less. Dying, I learned this week can, under some circumstances, be a beautiful part of life.

Last Shabbat’s Parashah was Vayechi, “And he lived,” which describes Jacob’s death. The patriarch gathers his children. He blesses his grandchildren. He leaves instructions for his burial. He speaks to each of his sons. Then he lays down and “is gathered to his people.”

This special way of describing death implies a type of reunion with previous generations, possibly with loved ones who have passed. It suggests that dying is an experience that is decidedly not solitary. The word the Torah uses for “people” is actually plural, עמיו, “peoples,” as if to say “when you die you will not be alone.”

The Jewish prayers often associated with death imply a presence that accompanies the dead.

Psalm 121, part of the canon of Psalms in funerals and burials, puts it this way:

יְהוָ֥ה שֹׁמְרֶ֑ךָ יְהוָ֥ה צִ֝לְּךָ֗ עַל־יַ֥ד יְמִינֶֽךָ׃

YHVH is your shomer, your guardian companion, the shadow by your side.

After Jacob breathes his last, we immediately hear about a kiss:

וַיִּפֹּ֥ל יוֹסֵ֖ף עַל־פְּנֵ֣י אָבִ֑יו וַיֵּ֥בְךְּ עָלָ֖יו וַיִּשַּׁק־לֽוֹ׃

“Joseph flung himself upon his father’s face and wept over him and kissed him.”

In our tradition, that kiss is expressed in a variety of physical and spiritual ways. People sit with the body from death until burial, often reciting Psalms. The body is washed and purified, while the washers recite love poetry from the Song of Songs. Some bodies get cleansed in the Mikvah. All of this comes out of a loving concern for the soul, which is imagined to still be present in the vicinity of the body until burial.

Finally, after family and friends express their love and appreciation, the body, now dressed in soft cloth, is laid to rest, and then lovingly covered with the earth from whence it came.

The tradition is signaling to us the importance of a death of beauty. Death is not separate from life, but an integral part of it, and for some it can be a truly wonderful part, if we treat it with the right attention and care.

As I spent the last week with a dear grandparent preparing to pass, I marveled at the sweetness of a blessed departure. Family gathered around her in her final days. She blessed them all and thanked them, and they her. Once she passed, her body received the full treatment that Jews offer their dead. It was as beautiful a death as one could hope for.

This week brought into sharp relief the the brutal deaths of so many Palestinians and Israelis over the last months, many of whom did not even receive proper burial, never mind the unspeakable moment of death itself. This never-ending war in Gaza has robbed so many people of their lives. And it has robbed almost all of those who lost their lives from a loving, dignified death as well.

Let this at least remind us of the glory of a dignified passing, and help us seek the sweetness and blessings in times of transition and loss.Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Small Moral Acts

by Rabbi Misha

“Never underestimate the power of one small moral act.” This was one of the lines that stuck with me from my father’s talk about the West Bank on Monday.

For those of you who missed it, David Shulman's talk about the situation in the West Bank during the war.

Dear friends,

“Never underestimate the power of one small moral act.” This was one of the lines that stuck with me from my father’s talk about the West Bank on Monday. When contemplating this week’s parashah the following morning, I realized that this is a defining characteristic of Jewishness, or at least of the biblical character after whom Jews are named, Yehudah, or Judah.

The parashah begins with the greatest Hail Mary in the Bible. Joseph and his brothers have been estranged for decades, since they sold him into slavery. Now the brothers come in front of Joseph a second time to beg for food. Joseph responds by angrily imprisoning Benjamin and telling the rest of them to go back to Canaan. The relationship is on the verge of becoming irreparable. If they leave, Jacob will die of sorrow, and the brothers will forever live in animosity. It is at this moment that Judah steps into action. There is no reason for him to think that what he is about to do will help. Joseph has planted stolen goods on them and used it as proof to imprison Benjamin. He sits on his throne surrounded by advisors and guards. He has not shown openness to anything other than deciding things on his own.

However, Judah’s desperation seems to move him toward a simple, crazy act:

ויגש אליו יהודה

"And Judah approached him."

The early translators of Torah into Aramaic translate this: “And Judah came close to him.”

This act, which shouldn’t have helped, only endangering the brothers further, radically changes everything. After decades of separation, anger and guilt, this step toward him brings tears to Jospeh’s eyes, and completely shifts the relationship toward forgiveness and love.

On Tuesday evening I was invited to speak at a protest of Israelis for Peace in Columbus Circle calling for immediately returning the hostages, a bilateral ceasefire and the Netanyahu government to resign. There I described this moment in the Parashah as exactly like the political moment in Israel/Palestine. There are two options on the table: solidifying our mutual relationship of hatred, anger and guilt for another few generations, maybe for good, or attempting a small, Judean act of approach.

The Netanyahu government will not make such an approach. “Never, ever,” as my father put it on Monday. “He will fight it tooth and nail,” he said. Netanyahu’s entire political life has been designed to prevent a Palestinian state. The ethos of separation, expressed in the Joseph story by living for decades with no knowledge of each other’s lives, and on the ground with walls and fences, has failed. Crazy as it might sound to Israelis who are licking their wounds and whose distrust of Palestinians is higher than ever; and crazy as it might sound to Palestinians who are still dying every day, this, now is literally the pivotal moment.

After Judah’s approach, and his soft speaking in Joseph’s ear, Joseph sends out of the room everyone other than the brothers, and weeps loudly. He tells his brothers who he is, and they are so shocked that they move away from him. It’s then that Joseph makes a gesture like his older brother did.

גשו נא אלי

“Come close to me,” he says, and the Torah continues, “And they came close.”

“Don’t be angry at yourselves,” he tells them, and one can hear him speaking to himself too: don’t be angry, Joseph.

It is then that Joseph suggests an end to the physical separation as well:

“Come down to me from Canaan, do not stay standing where you are. Instead, sit in the Land of Goshen and be close to me.”

This is the first of nine mentions of The Land of Goshen in the Parashah. Goshen is a kind of suburb of Cairo. It’s strange to have that many mentions of it in such a short segment. It’s as if I’d tell you to come live in Hoboken, and just keep saying Hoboken over and over and over until you start thinking I’m trying to communicate something else. Goshen comes from the same root of the word Vayigash. It can be understood less as an actual place, and more of a state of mind: It is the place of coming close, the town of pivots, the city of approaches against all odds; the land of small moral acts.