Sort by Category

The Great Crocodile

by Rabbi Misha

Kabbalistic wisdom on God, good and evil for the week of January 6th.

Dear friends,

Imagine yourself being invited into the unknown by some gentle voice. Imagine that what you hear in that voice is the voice of your beloved, or maybe your mother, someone you trust beyond everyone else. They take your hand and walk you into one room, then another, each room going deeper and deeper into some beautiful, majestic home. After many wonderous rooms you enter the largest one yet. A few stairways spiral upward, all leading to the same place, the seat of The Great Crocodile.

This is the Zohar’s depiction of the first verse of this week’s Parasha, Bo:

God said to Moses: Come to Pharaoh.

When Moses, with the Holy One’s gentle guidance, arrives at these stairways, he understands a few things: The creature at the top is an expression of Pharaoh. The crocodile is divine, a feature of God. Moses can see that Pharaoh and everything he represents is מִשְׁתָּרִשׁ בְּשָׁרָשִׁין עִלָּאִין, rooted in the high realms. He also knows that he is supposed to walk up those stairs and confront this crocodile. But he won’t. He is too scared, paralyzed by the ramifications of what he has seen.

The Zohar is neither scared nor paralyzed. It isn’t interested in a comfortable notion of divinity, or a neat and pleasant idea of good and evil. It isn’t looking for the Torah to be clear-cut and self-affirming. It is actively seeking out the challenge to its own ideas of right and wrong. It’s not only Pharaoh and the Egyptians who thinks he is a god, but Moses and the Jews can see the truth in that too. Moses enters into God and finds Pharaoh there.

God, like us, is not only good. I’ll repeat that. God is not only good. Godliness is inclusive of every aspect of existence, every possibility of our imagination, every dark wish. Every lie exists therein. Every selfish act, every expression of chaos, every tweet and every feeling of despair; everything is included in God. How could it not be, in a system in which God is understood to be the creator of everything, the life-source and death-source in whose image we live?

What you hate is part of you.

Who you blame is inside of you.

Your oppressor is not absent in your oppressed self, nor even in your liberated self.

Acceptance of reality is important. Without it we are shooting in the dark, or groundlessly dreaming. The Great Crocodile can be a beautiful teacher.

“The mystery of the wisdom of ‘The Great Crocodile hanging out in his river’ has been demonstrated to those seekers who know the mysteries of their God,” says Rabbi Shimon in the Zohar.

And yet, this does not mean that we are supposed to accept reality quietly. The lesson may well be about when to confront the earthly expressions of the crocodile, and how to beat and subdue it.

When Moses is standing there frozen in fear of the reality he has just learned, God steps in.

“When the blessed Holy One saw that Moses was afraid, He said to (the crocodile) ‘I am against you, Pharaoh king of Egypt, the Great Crocodile hanging out in his river…’ The blessed Holy one, and no one else, had to wage war against him…”

God must wage war against pieces of God’s-self, and so must we. This is true on a personal level, a societal level and a global level.

This evening we will have a special Shabbat, in which Rabbi Jim Ponet and New Shul co-founder Ellen Gould will help us think and sing through what we have to learn from, and how we can confront and subdue The Great Crocodile, on the week of the anniversary of the insurrection.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Moments

by Rabbi Misha

A year is made up lots of little moments.

Dear friends,

As the year comes to close I find myself thinking back to the smaller moments that have constituted the vast majority of 2021. These were of course in certain ways colored by the bigger events. Biden came into office, the vaccine rollout, waves of the pandemic, the constant knowledge that people are sick and that many are dying. 100 shades of confusion as to how to act and when to act differently and what each different stage and new bit of information means or doesn’t mean. There were big changes in peoples personal lives as well. Changing work situations, adapting to new stages of life, health issues that have come and gone, happy occasions and trying occasions and sad occasions.

Between each of those there was a lot of living. A lot of doing the things of the every day, surrounded by the people who we are used to seeing. There were meals, and movies, and walks, And doing nothings. There were moments of thinking, talking and reading. So much of the time we spent was good. Even when overall many of us experienced difficult times.

In this weeks Parasha Moses asks god a question:

למה הרעות לעם הזה?

Why did you make things so bad for the people?

The people are in a tough spot. They’ve been slaves for a long time. Pharaoh’s been tightening the grip, and when Moses shows up and convinces them it’s time to stand up and get free, pharaoh responds with even more hardship. It seemed as though redemption was at hand, but instead it’s taken them backwards. That’s when Moses asks his question.

Why did you make things so bad for the people?

God gives a strange answer.

”I appeared to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob as El Shaddai, but I did not make Myself known to them by My name יהוה.”

Until now, says God, I’ve appeared as the god Shaddai. Now I am making my first appearance to you and the rest of the people for the first time as YHVH, or Adonai. Shaddai derives from the Hebrew word for a woman’s breast, Shad, and therefore carries with it a strong maternal connotation. It’s as if until now God was mothering the people, caring for them like one does for a baby, protecting them, feeding them. Now, as the nation grows up God manifests as the strange, past-present-future of the verb To be. The story of redemption, of moving to the next stage in life, is composed of infinite moments of being. Some large moments, some incredible moments, some terrifying moments, and mostly lots and lots of little moments in which to be.

The Hebrew word for moment, rega, is where the root for the word for calm, ragua comes from. To be calm is to embody the moment, to be “momented.” I wish us all a year filled with countless moments of calm that come together like a puzzle to form the next step on our path out of the narrows to ever expanding freedom. May we manage to enjoy the moments as they come, to think back to the sweet moments that we experienced this last year, and to create a time of healing and freedom for all.

Happy 2022!

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Practicing Lightness

by Rabbi Misha

Days like these demand a light state of being if we do not want to fall into despair, anger and depression.

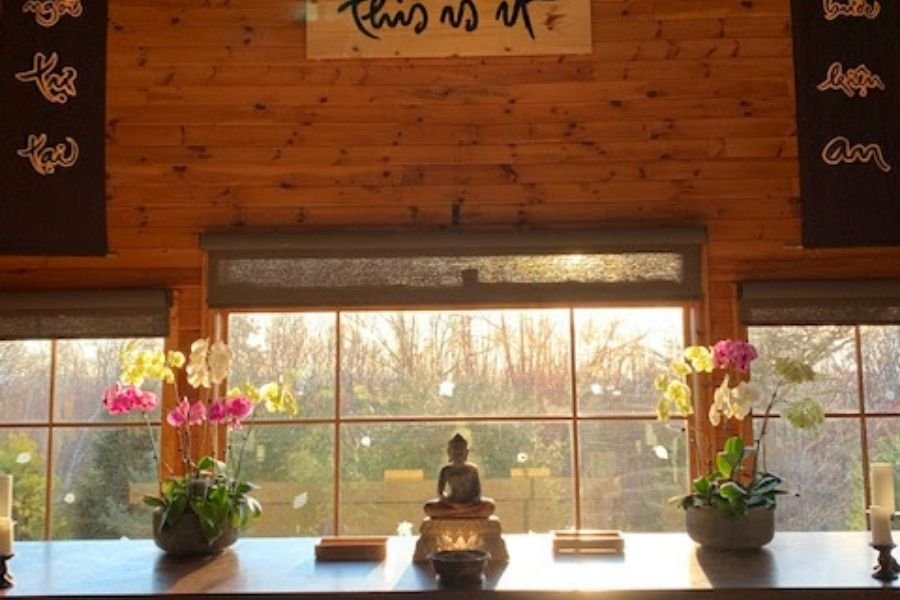

Blue Cliff Monastery

Dear friends,

Lightness is not a state of being that the Jewish tradition tends to espouse. Ours leans towards the weighty, the digging into concepts complicated and deep, toward responsibilities placed on our shoulders for the sake of preserving our tradition, healing the world and doing what we were placed on this planet to do. The Hebrew word for light (the opposite of heavy), Kal, appears a whopping zero times in the Torah. The few times in which the verb using the three-letter root of Kal appears in Torah are anything but light. Sarah feels like she has “become light” in the eyes of Hagar, meaning she doesn’t respect her enough. Children who “mekalel” their parents, understood as curse but literarily lighten, are to be put to death. Moses offers us “the blessing or the curse,” the brachah or the klalah, the latter also deriving from the same root, ק-ל-ל.

But days like we are experiencing lately demand a light state of being if we do not want to fall into despair, anger and depression.

I was reminded this week of the deep sense of gratitude I had toward Quentin Tarantino after I watched Inglorious Bastards. This Holocaust revenge movie could have never been made by a Jew. We needed a friend to come and make it for us. Another friend showed up for me to help me lighten my attitude.

“We need to cultivate a spiritual dimension of our life if we want to be light, free and truly at ease,” writes the Vietnamese Buddhist teacher Thich Nhat Hanh. “We need to practice in order to restore spaciousness.”

I had the wonderful opportunity to spend a couple days at one his followers’ monasteries last week, Blue Cliff Monastery in the Catskills. It gave me an opportunity to practice this light spaciousness, as well as find some tools to retain a degree of lightness after I came back. Since returning several things have happened that would normally leave me feeling heavy and miserable: Omicron exploded, my son got sick, all my kids stayed home from school for a week and we had to cancel our family holiday plans. Throughout this time, my mind and heart have fared far better than usual thanks to Thich Nhat Hanh’s teaching on the practice of lightness.

What has this practice consisted of?

A few minutes of meditation in the morning, a few minutes of washing the dishes (especially pots and pans, which I usually hate washing) in the afternoon, and a few minutes of playing with my kids in the evening. During each of these events, in place of my habitual attempt to finish these tasks so I can get to the real thing I want (AKA “need”) to do, I make an effort to simply breathe, relax, and enjoy what I’m doing. Breathing, I’m finding, can be an enjoyable activity.

It’s not always simple, of course. But the experience of carrying the world on your shoulders, of weight and noise and mayhem, of the disaster inherent in not accomplishing this or that task, is often just an experience. We can work on disassociating ourselves from that weight.

The truth is that our tradition does teach these lessons as well. The psalmist wrote:

שויתי יהוה לנגדי תמיד

I see YHVH in front of me always.

YHVH, of course simply means being.

In whatever we do, we can try to keep the present moment in front of our eyes, rather than everything that isn’t there. We can ask ourselves: where in our lives are we being unnecessarily heavy? What are we experiencing as weight, which in our moment-by-moment reality has no actual existence?

In our Saturday morning prayers we find the Hebrew word for light denoting a desirable state of mind, which opens up the door to gratitude. I will leave you with the words of Ilu Finu, and wish you a Shabbat of lightness, spaciousness and ease, and a sweet birthday of our friend Jesus Christ:

Were our mouths as full of song as the sea,

and our tongues as full of melodies

as its multitude of waves,

and our lips as full of praise

as the breadth of the heavens,

and our eyes as brilliant as the sun and the moon, and our hands as outspread as the eagles in the sky ---

and our feet as light as gazelles’

Even then we would be able to thank you only for one millionth of a millionth of the blessings we live with every day.

אִלּוּ פִינוּ מָלֵא שִׁירָה

כַּיָּם וּלְשׁוֹנֵנוּ רִנָּה כַּהֲמוֹן גַּלָּיו

וְשִׂפְתוֹתֵינוּ שֶׁבַח כְּמֶרְחֲבֵי רָקִיעַ

וְעֵינֵינוּ מְאִירוֹת כַּשֶּׁמֶשׁ וְכַיָּרֵחַ

וְיָדֵינוּ פְרוּשׂוֹת כְּנִשְׂרֵי שָׁמַיִם

וְרַגְלֵינוּ קַלּוֹת כָּאַיָּלוֹת:

אֵין אָנוּ מַסְפִּיקִים לְהוֹדוֹת לְךָ

יְהֹוָה אֱלֹהֵינוּ וֵאלֹהֵי אֲבוֹתֵינוּ

וּלְבָרֵךְ אֶת־שְׁמֶךָ עַל־אַחַת

מֵאֶלֶף אַלְפֵי אֲלָפִים

וְרִבֵּי רְבָבוֹת פְּעָמִים

הַטּוֹבוֹת נִסִּים וְנִפְלָאוֹת

שֶׁעָשִׂיתָ עִמָּנוּ וְעִם־אֲבוֹתֵינוּ מִלְּפָנִים:

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

No Rewards Please

by Rabbi Misha

One of the most helpful concepts Jews have come up with, and one of the hardest to accomplish is called “Lishma”

Dear friends,

During the 7+ years I was studying toward ordination people would often ask me “what are you going to do once you’re ordained?” I consistently had no answer. I didn’t know what I wanted to do as a rabbi. I barely understood why I was doing it in the first place, other than some internal pull met with some external encouragement. I knew I was in it, and doing it and that it was important to me to complete it and to do it right. It was one of the few things in my life thus far that I managed to do without giving too much thought to what I will get out of it or what purpose it will serve. That kept the process both fresh and edgy and allowed me to reach the ordination ceremony open to what might come. A few months later I was rewarded with the wonderful opportunity to jump on this sweet, curious looking boat called The New Shul.

One of the most helpful concepts Jews have come up with, and one of the hardest to accomplish is called “Lishma,” or “for its own sake.”

Maimonides wrote in Mishneh Torah:

Let no man say: "Behold, I perform the commandments of the Torah, and engage myself in its wisdom so that I will receive all the blessings described therein, or so that I will merit the life in the World to Come; and I will separate myself from the transgressions against which the Torah gave warning so that I will escape the curses described therein, or so that I will suffer excision from the life in the World to Come". It is improper to serve the Lord in such way, for whosoever serves the Lord in such way, is a worshiper because of fear, which is neither the degree of the prophets nor the degree of the sages. And the Lord should not be worshiped that way.

Torah, to Maimonides was far larger than just the commandments. To the rabbis in Talmudic times Everything we do is Torah, from the loftiest study to the way they used the restroom. Maimonides may be focusing on Torah, but his words apply to almost everything we do. If there is too strong a utilitarian aspect in most things we do, if we are too often trying to extract things out of our actions we may, from this vantage point, have a problem. Any action that is performed in an attempt to squeeze something out of it for your benefit is not an action done “lishma.” The capitalist system, and the American reality both lead us toward utilization rather than to a quieter type of “being with” what we are doing.

Personally, I find myself constantly trying to accomplish tasks. Be they work or house or family related, so much of what I do is an attempt to complete the things that I believe need to be done. Even in the category of gaining knowledge, or creativity, or experience, I can fall into the habit of “accomplishing things,”rather than doing them for the sake of doing them. I might read a book for the sake of completing all of a certain writer’s work. I might study Talmud for the purpose of finding a particular piece of information, or read the Parasha in order to have what to write to you on Friday. I might practice my musical instruments so that I can bring in a song to Shabbat. Even the articles I choose to read in the publications I choose to follow are often chosen simply for the sake of re-enforcing my opinions. Confirmation bias is a good example of not “lishma.”

In a way there’s nothing wrong with any of those examples. Certainly judging ourselves isn’t helpful. Sometimes, as was coined in the Talmud: מתוך שלא לשמה בא לשמה

“Out of not lishma comes lishma,” or: out of doing something not for its own sake one learns to do it for its own sake. True though that may be, our countless actions done not “Lishma” often feel deeply misguided.

We need to work on releasing the utilitarian aspect of as many of our actions as we can, and simply doing them for the sake of doing them. When we manage to do that, often rewards come of their own accord. When you manage to be there with another person without an agenda, often the depth of communication is deeply enhanced. In study I often find that the deeper realms reveal themselves as soon as I manage to let go of my pre-conceived ideas of what will happen in the study session.

In the Mishna we find the following description:

Rabbi Meir said: Whoever occupies himself with the Torah for its own sake, merits many things; not only that but he is worth the whole world. He is called beloved friend; one that loves God; one that loves humankind; one that gladdens God; one that gladdens humankind. And the Torah clothes him in humility and reverence, and equips him to be righteous, pious, upright and trustworthy; it keeps him far from sin, and brings him near to merit. To him are revealed the secrets of the Torah, and he is made as an ever-flowing spring, and like a stream that never ceases. And he becomes modest, long-suffering and forgiving of insult. And it magnifies him and exalts him over everything.

Seeking rewards, says Rabbi Meir, prevents you from reaping them. Not seeking them showers you with countless rewards.

Singing is one of the hardest things to do not “lishma.” It is often a moment of freedom from our capitalist way of life. Music can help us treat our actions with more presence, intention and softness; To open us up to the unexpected. That’s why we will be devoting our Kabbalat Shabbat this evening to music and song as we look to welcome Shabbat “lishma.”

I hope to sing with you this evening at 6:30pm at the 14th Street Y, or on Zoom with our musical guests cantor and singer Raechel Rosen, and percussionist Yuval Lion.

Shabbat's Zoom Link here.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Choreography of Nearness

by Rabbi Misha

One of my closest childhood friends became very religious when we were 16. Over the course of a year or two he transitioned from being the kid that introduces cheeseburgers to his slightly more traditional Jewish friends, to a bearded aspiring rabbi.

Dear friends,

One of my closest childhood friends became very religious when we were 16. Over the course of a year or two he transitioned from being the kid that introduces cheeseburgers to his slightly more traditional Jewish friends, to a bearded aspiring rabbi. A year ago I asked Reb Leibush, now the head of a yeshiva in Jerusalem what sparked that transition. He answered like he answered me decades ago. He took three steps back before praying the Amidah, then three steps forward. During the time of that not very long prayer, before he concluded with three more steps back, bowing all around and two steps forward, something happened to him that he couldn’t ignore, nor define, but he knew that his life had changed.

The Amidah, our central prayer of request, our longest moment of silence, our standing time when our feet are fixed in place, this is our most intimate moment with God (or ourselves) in our prayers. There are physical preparations for this prayer as well as mental ones prescribed. Mental prep includes prayers of praise and gratitude, assertions of our world view and the limits of our knowledge, songs, devotional poems. Then come the physical actions: we turn our bodies toward Jerusalem, we take three steps back and three steps forward, and begin.

The strange magic of these dance moves, choreographed by rabbis for us thousands of years ago is illuminated in this week’s Parasha, Vayigash.

We find ourselves in the climax of the Joseph saga. He’s already been sold to slavery by his brothers, taken to Egypt, imprisoned unjustly, and used his understanding of dreams to become Pharaoh’s right hand man. He has saved Egypt from a terrible famine, and has already given food to his brothers, who have come from Canaan looking to stave off starvation. He hasn’t revealed himself to them though he certainly recognizes them. The second time the brothers come back after the food Joseph gave them has run out he devises a trick that puts his one full blood brother, Benjamin in prison. The defacto leader of the brothers, Yehudah now must respond.

וַיִּגַּ֨שׁ אֵלָ֜יו יְהוּדָ֗ה

And Judah approached him

This approach, the title of the parasha, is one of the three sources that inspired our pre-Amidah choreography:

The reason (for taking three steps before the Amidah) is because there are three “approaches” in prayer (found in Tanach): “And Avraham approached,” “And Yehudah approached,” “and Eliyahu approached.”

(Rabbi Avraham Eliezer bar Isaac)

The three instances where the word “Vayigash”, “and he approached” appear in the bible are followed by deep, honest expressions of a major need.

Rabbi Moshe Iserles writes:

“When a person is about to pray [the Amidah], he should take three steps forward, like someone approaching and drawing near to something that must be done.”

Yehudah had no choice. He had to get his brother out of prison or his father would have died of sorrow. And he will express this in clear language to this Egyptian ruler who he does not know is his brother. But before any words are said, he must first move his body nearer to him.

It is the silent physical movement that first grabs Joseph’s attention, signaling to him that something is about to happen. When we speak to our loved ones often a similar takes place. A physical movement away from them can signal fear, lack of clarity or care or love or importance. A movement toward them can signal a desire to engage, your need of your loved one and clarity of intention. It cries out: “I want to be close to you,” which can often be more effective than words.

In order to draw near, to come close, we must approach. This is the first lesson the rabbis learn from this moment of high drama and tension. Then come his words, ending with a selfless act of sacrifice:

Please let your servant remain as a slave to my lord instead of the boy (Benjamin), and let the boy go back with his brothers. For how can I go back to my father unless the boy is with me? Let me not be witness to the woe that would overtake my father!”

When we approach God or anyone else in this way, drawing near with selfless love of others, even if we have harmed them or done wrong, the response suggested in this story is a breaking down of barriers, inhibitions and anger into total and complete forgiveness:

Joseph could no longer control himself before all his attendants, and he cried out, “Have everyone withdraw from me!” So there was no one else about when Joseph made himself known to his brothers.

His sobs were so loud that the Egyptians could hear, and so the news reached Pharaoh’s palace.

Joseph said to his brothers “I am your brother Joseph, he whom you sold into Egypt.

Now, do not be distressed or reproach yourselves because you sold me hither; it was to save life that God sent me ahead of you... it was not you who sent me here, but God;

Wouldn’t it be nice if we could approach one another, and notice when we are being approached. Those quiet steps forward could be the beginning of knowing one and another more deeply, and the forgiveness that ensues from that knowledge.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Maoz Tsur

by Rabbi Misha

Before I share some thoughts on Hanukkah in advance of our celebration tomorrow, I’d like to acknowledge the anxiety and fear that the discussion in the Supreme Court on Wednesday may have provoked in many of you, especially women.

Dear friends,

Before I share some thoughts on Hanukkah in advance of our celebration tomorrow, I’d like to acknowledge the anxiety and fear that the discussion in the Supreme Court on Wednesday may have provoked in many of you, especially women. I find myself seriously impacted by the prospect of this decision, and have spent much of the last weeks thinking about the deeper meanings of this debate, and these two words “choice” and “life.” I will share some thoughts about all of this in the weeks ahead, and we are planning to address it in some of our gatherings as well, but for now I will just re-iterate that in the Jewish tradition the needs of the woman clearly supersede those of the fetus growing in her womb. If any of you would like to talk with me about this, or to organize around this issue please reach out.

We sing this song after candle lighting every night:

Ma'oz tsur yeshu'ati

lecha na'eh leshabeakh.

Tikon beit tefilati

vesham todah nezaveakh.

Le'et tachin matbeakh

mitsar hamnabeakh,

'az 'egmor beshir mizmor

khanukat hamizbeakh.

Poetry is hard to translate, which is why the translations out there are so terrible. Here’s one:

Rock of ages

Crown this praise

Light and songs to you we raise

Our will you strengthen

To fight for our redemption

It’s amazing how what people call a translation can offer nothing at all of the intention of the poet. I don’t know that I can do much better in poetic form, but I’ll try and give a sense of it in prose.

Maoz is a fortress, the place of condensed strength that cannot be broken.

Tsur is a foundational rock, the rock within a mountain that will never in our lifetime move. It is the one stable, constant and true piece of reality.

So Maoz tsur is the strongest inner core of the foundational rock.

Yeshuati means my redemption or salvation. My chance for improvement, for rising above, for becoming one with truth and goodness despite everything else going wrong in my world.

So Maoz tsur yeshuati is the strongest inner core of the foundational rock of my redemption. Fortress of the never changing rock of my best self.

Then we say – lecha na'eh leshabeach: to you, oh fortress, is it proper to give praise.

Tikon beit tefilati – literally the house of my prayer will be established. Here we clearly reference the Hanukkah story, and the return to the temple. But we can read this as any temple, the temple of our bodies, the place where we find peace, the home of our silence. This place will be established. And when it is, as we succeed occasionally in doing, then:

vesham todah nezaveakh: We will make an offering of gratitude there. When we manage to find this place of peace, we are able to see what we have, and to feel and express our gratitude with a zevach, a sacrificial gift that we offer out of love. Tomorrow at the party we will be making care packages for seniors with mental and financial problems. That will be our zevach todah, our gratitude offering.

We end the verse with these words:

'az 'egmor beshir mizmor

khanukat hamizbeakh.

Then I will conclude with a song. And what will that song accomplish? It will Hanukkah the alter; it will dedicate that alter of offering, the temple of our silence, and the work that is ahead of us to that fortress of truth, justice and goodness.

This medieval poem continues with several more verses, each one detailing a different dark time in our history. It is a poetic map of Antisemitic moments and sentiments which we somehow overcame. In each of these times of fear and oppression we managed to return to Maoz Tzur, this unshakeable truth at our core, this home, this quiet self. We managed, we could say, to return to YHVH.

Tomorrow we will acknowledge the ongoing problem of antisemitism, and look for our Maoz Tzur today. Our musical offering will be plentiful, with a special collection of incredible musicians including Frank London, Meg Okura, Trip Dudley and Yonatan Gutfeld. We will hear stories from elders, take part in an immersive play, fill our bellies with fancy latkes and ring the bells that still can ring.

Chag sameach and see you tomorrow at 3:30 at Judson.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Thank you

by Rabbi Misha

A prayer of gratitude from the daily prayers.

Dear friends,

A prayer of gratitude from the daily prayers:

We thank you

Our fountain

And fountain of our mothers and fathers

Slow painter of our lives,

Watchful keeper of our hope

In every generation, that's You.

We continue to thank you

By telling your tales of love:

Our lives in your hands

Our spirits in your care

Your miracles accompanying us day by day

Your evening wonders

Your morning silence

Your afternoon delights.

Goodness; whose compassion will not end.

Compassion; who won't stop acting like a lover.

Whatever’s left of us turns to face You

Now

For all of it

Be blessed

Be praised

Be carried on our lips

And hearts and minds

Always

מוֹדִים אֲנַֽחְנוּ לָךְ שָׁאַתָּה הוּא יְהֹוָה אֱלֹהֵֽינוּ וֵאלֹהֵי אֲבוֹתֵֽינוּ לְעוֹלָם וָעֶד צוּר חַיֵּֽינוּ מָגֵן יִשְׁעֵֽנוּ אַתָּה הוּא לְדוֹר וָדוֹר נֽוֹדֶה לְּךָ וּנְסַפֵּר תְּהִלָּתֶֽךָ עַל־חַיֵּֽינוּ הַמְּ֒סוּרִים בְּיָדֶֽךָ וְעַל נִשְׁמוֹתֵֽינוּ הַפְּ֒קוּדוֹת לָךְ וְעַל נִסֶּֽיךָ שֶׁבְּכָל יוֹם עִמָּֽנוּ וְעַל נִפְלְ֒אוֹתֶֽיךָ וְטוֹבוֹתֶֽיךָ שֶׁבְּ֒כָל עֵת עֶֽרֶב וָבֹֽקֶר וְצָהֳרָֽיִם הַטּוֹב כִּי לֹא כָלוּ רַחֲמֶֽיךָ וְהַמְ֒רַחֵם כִּי לֹא תַֽמּוּ חֲסָדֶֽיךָ מֵעוֹלָם קִוִּֽינוּ לָךְ:

וְעַל־כֻּלָּם יִתְבָּרַךְ וְיִתְרוֹמַם שִׁמְךָ מַלְכֵּֽנוּ תָּמִיד לְעוֹלָם וָעֶד:

Wishing you all a happy Thanksgiving weekend!

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Us and the Stars

by Rabbi Misha

Imagine you knew the constellations as well as you knew your neighborhood. Like you knew how to get from the subway stop to your apartment, you knew the way from the Big Dipper to Orion.

Ben Shahn

Dear friends,

Imagine you knew the constellations as well as you knew your neighborhood. Like you knew how to get from the subway stop to your apartment, you knew the way from the Big Dipper to Orion. Like you could make your way from Lincoln Center to Grand Central you could follow the stars from Aquarius to Gemini. This used to be a much more common human ability but it was always rare. In the Talmud we find one true expert of the heavens. “Shmuel said: the paths of the skies are as clear to me as the paths of Nehardea (the town he lived in).” An intimacy with the night skies is something we city dwellers seem to have largely lost.

A couple weeks ago the stars entered my living room. My cousin shipped me a painting that belonged to my grandmother, with text from the Book of Job under an abstract depiction of the night sky. Painted by Ben Shahn, a Jew who traversed the paths from the old world to the US, from Cheder (parochial school) to the world of political art, the painting has brought with it soft questions of our place in the universe, gentle queries about the ways we walk the earth, and new readings of the Book of Job.

The stars serve a few different purposes according to our creation story.

והיו לאתת ולמועדים ולימים ושנים

They will serve as signs, and holidays and days and years.

Signs that suggest where we might go. Holidays that we can stop and mark special times. Days that we might stay connected with the slow movement of the everyday. Years that we can feel the flow of our lives, its circularity as well as its changing nature.

Life here on the ground beneath the stars is not always easy. We struggle to see those signs up there.

The text in the painting is part of God’s speech to the ultimate sufferer, Job toward the end of the book. You’ll recall that Job was a rich, happy man, who had his entire life implode, losing his children, his wealth and health, and his trust in the goodness of God. After thirty some chapters of theological poetry about the question of bad things happening to good people, God finally speaks. God’s speech is most easily understood as a scolding. General sentiment: Who are you to complain at me, you little speck of dust?! But staring at these verses sitting under Shahn’s constellations has softened God’s words from angry rhetorical questions, to just plain questions:

הַֽ֭תְקַשֵּׁר מַעֲדַנּ֣וֹת כִּימָ֑ה אֽוֹ־מֹשְׁכ֖וֹת כְּסִ֣יל תְּפַתֵּֽחַ׃

הֲתֹצִ֣יא מַזָּר֣וֹת בְּעִתּ֑וֹ וְ֝עַ֗יִשׁ עַל־בָּנֶ֥יהָ תַנְחֵֽם׃

הֲ֭יָדַעְתָּ חֻקּ֣וֹת שָׁמָ֑יִם אִם־תָּשִׂ֖ים מִשְׁטָר֣וֹ בָאָֽרֶץ׃

Can you tie sweet cords to Pleiades

Or undo the reins of Orion?

Can you lay out the constellations each month,

Or keep the North Star in her mothering spot?

Do you know the laws of the sky

Or the way they govern the earth?

There are answers to these questions beyond the simple “No” that most people have seen in them. Instead of a slap on the wrist or a trodding upon I have begun to see them as an invitation to participate in the heavenly play. Sitting under the loving painted sky I can’t help but notice how Shahn has tied sweet cords to Plaides, connected me to them and them to the other constellations. Or how Shmuel, like many star gazers learned the laws of the sky, and how some part of me understands the way they are connected to my life. Even though we rarely see the vast majority of the stars, many of us still know the way they were aligned on the day, the hour and the minute we came out from the dark to the place where they can be seen. There is hidden love and protection in this universe that we can look for, imagine, discover, take part in and know, even in - especially in - our darkest moments.

Wishing you a shabbat filled with stars.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Strong Women

by Rabbi Misha

Divine though it may be, the Torah was written by and about men.

Judy Chicago, The Creation from the Birth Project, 1982

Dear friends,

Divine though it may be, the Torah was written by and about men. We can see direct lines between the Tanach and the abortion law in Texas, the backwards attitude toward parental leave in this country and the war on women around the world. All of this provides one of the most exciting opportunities religion has to offer: the chance to participate in reshaping it through new practices and re-interpretation of the ancient texts. I feel empowered when I can see the direct line not between the Torah and the current expressions of the patriarchy but between the Torah and the work of feminist artists like Judy Chicago, or even singers like Cardi B.

I get especially excited when a young person clues me in to the subversive feminine voice in the Torah. These past weeks I’ve been learning from a 13 year old young woman named Willow, a member of the Shul who will be rising to the Torah at her Bat Mitzvah tomorrow. She looks at this week’s parashah and doesn’t see the story of Jacob leaving Canaan to Mesopotamia to find a wife, but of Rachel, who sets her eyes on a young man that turns up at the well, and decides to create a family with him.

When Rachel’s father, Laban tricks Jacob into having sex with her older sister, Leah (and in that act solidifying their marriage), the Torah points our attention to Jacob. But in Willow’s narrative we are looking at how this impacts Rachel, as well as Leah. When a decision to leave and head back to Canaan after 20 years happens, Willow sees the two women as the initiators of that move.

The amazing thing is that once you make that switch in your mind it’s hard to see the text of Genesis as anything but that way.

In God, Sex and The Women of the Bible, Rabbi Shoni Labowitz z”l wrote: “When you change the story, you can change the whole culture. This is what the patriarchal era did in history, and women have the power now to correct it.” Labowitz, who knew well how the (male) rabbis over the centuries diverted the story toward an even more male-centered approach, seems to be suggesting that the Torah may be more gender-neutral than we are used to thinking about it, and can therefore be reclaimed by women through interpretation.

The contemporary practice of Midrashey Nashim, stories and commentaries on the Torah written by women is an important piece of this work. Women like Tamar Biala and Chana Thompson, who take the traditional form of Midrash, stories that flesh out the stories in the bible, but do it with a woman’s viewpoint are hard at work. Yael Kanarek, whose Re-gendered Bible flips all the genders in the Torah to create a new impression on the reader, is a downtown artist deeply engaged in Torah and its reboot.

And just like in any of the struggles for women’s liberation, we shouldn’t forget that men can play an important role as well as allies. The struggle for a just Torah is the struggle for a just society for all of us. Perhaps we could all start with hearing the women in the stories of this week’s parashah, as Willow has helped me do.

If you’d like to give that a try, a wonderful place to start is in the Shul’s Women of the Bible Chevrutah, led by Elana Ponet. For more info click HERE.

I hope you can join us this evening for Kabbalat shabbat at the 14th Street Y (or on Zoom), where we will have a conversation about one of Rachel’s strongest and strangest moments in Torah, and the echoes we might see of her actions today. We will be joined by Yacine Boulares, a wonderful French-Tunisian saxophone player and composer.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Wine, Cheese and Ben and Jerry's Ice Cream

by Rabbi Misha

This week I posted a note on the Shul’s Instagram about State Comptroller Tom DiNapoli’s decision to divest New York state’s pension fund from Unilever, the parent company of Ben and Jerry’s.

Dear friends,

This week I posted a note on the Shul’s Instagram about State Comptroller Tom DiNapoli’s decision to divest New York state’s pension fund from Unilever, the parent company of Ben and Jerry’s. DiNapoli based his decision on Cuomo’s 2016 executive order forbidding the state to do business with supporters of the Boycott Divestment and Sanctions movement (BDS). I wanted to take the time to lay out some of my thinking on this issue that is close to my heart, which led me to post about it, and, I’m sorry to say, upset some of you.

Before that, however I’d like to explain that I see my role as rabbi as one entangled with ethics and morality rather than “the news”. When I read the newspaper as Misha I have all kinds of thoughts and opinions about whatever I read. When I take action on an issue as Rabbi Misha it is because I see ethical implications which transcend the current moment and speak to the moral bedrock of our tradition and our people’s history. That was the case this week.

Let me also clarify that what I posted this week had little to do with BDS. That was actually one of the points I was trying to make: that DiNapoli was using an anti-BDS law to penalize a company for an action that has nothing to do with BDS. You see, BDS is a movement to boycott, divest and sanction the State of Israel as a whole. They make no distinction between Israel proper, the land inside the internationally recognized 1967 borders, and the Occupied Palestinian Territories. To the BDS movement as a whole, the Israeli settlers of Chavat Maon - who have beaten my father and terrorized and assaulted countless Palestinians - and the residents of the Jewish-Arab village Neve Shalom, are the same.

Ben and Jerry’s takes a different stance. Their action did not comment on the legitimacy or lack thereof of the State of Israel. They self-define as “Jewish supporters of the State of Israel.” The boycott they announced is limited solely to the Jewish settlements in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. They wrote in the NY Times that what they did is not a rejection of Israel but “of Israeli policy, which perpetuates an illegal occupation that is a barrier to peace and violates the basic human rights of the Palestinian people who live under the occupation.”

Throwing this kind of boycott into the same basket as BDS amounts to silencing criticism of the state. It’s the same as telling critics of Egypt or China or India--or any of the other countries around the world doing horrific things--to keep quiet. There is a reason why so many American Jews I meet are afraid to speak their minds, or even to hold an opinion on Israel/Palestine, and it has to do with messaging like this.

Ben and Jerry’s is not questioning the legitimacy of Israel. They are questioning the legitimacy of a brutal 54 year-long occupation, and the actions of the State of Israel to fill the territory with Jews and create a system of segregation and oppression.

Ben and Jerry’s is not saying that Israel is the worst country in the world. They know like we do that China is holding a million people in concentration camps and forcing them to pick the cotton that ends up on your clothes and mine. They know like we do that half of the population of Afghanistan and many other countries is under attack daily by the men who run it. They know that LGBTQ people are killed by the state in many countries in the world. They know that this country is still chasing black people at the border on horseback and keeps close to two million mostly black and brown people in prison.

The reason they singled out one government is because of what I began with. It has to do with who we are. They clearly identify with Israel. They care about what goes on there. They feel a stake in it. And they were moved to take a stand on the one country that claims to speak for them as Jews.

They’ve come to the same conclusion that many of the Israelis I know have arrived at: there’s something wrong with buying wine made in Jewish owned vineyards near Nablus, or cheese made in Jewish-owned farms outside of Hebron, both of which sit on lands confiscated from Palestinian farmers. It’s somehow different than wine or cheese from Binyamina, south of Haifa.

We could agree with them or we could disagree. But to try to silence them in this uninformed way, which doesn’t even rise to the standards of the executive order that DiNapoli claims as his reason (and the rest of the politicians in the state have been mum on), is wrong.

מבשרך לא תתעלם, implored Isaiah, Do not ignore your own flesh.

Ben and Jerry’s refused to ignore the pain they feel over their ancestral homeland. They are choosing to engage, rather than to step back and say: “Oh it’s just so crazy over there.” They’re choosing to step in, despite the serious financial damages they stand to lose, rather than to hide.

In this week’s Parashah we are introduced to our ancestor, Jacob, whose name will be changed next week. “You will no longer be called Jacob” the angel says to him. Jacob, the little brother of, the one who comes in the heel of (the literal meaning of his name), the follower who did what Mommy told him and ruined his relationship with his brother. No more of that. From now on, the angel tells him, you will have your own name, the name of one who doesn’t shy away, but struggles, leads and takes risks. “Your name will be Israel, because you have struggled with God and with humans and were not beaten.”

Israel means to wrestle. Whether or not we agree or disagree with what they’ve done, Ben and Jerry’s is wrestling with Zion. Let’s not divest from wrestling. I hope you write me back some wrestling notes with whatever you may be thinking or feeling about this flawed communication.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Standing the Face of God

by Rabbi Misha

The Merriam Webster dictionary gives thirteen different meanings for the word “stand” as an intransitive verb, 7 as a transitive verb, and 3 of what they term the essential meaning of the verb. Each of them is true to how we use the word in English. None touch upon how the rabbis understand the word.

Lot's wife standing in perpetual prayer in the Judean Desert.

Dear friends,

The Merriam Webster dictionary gives thirteen different meanings for the word “stand” as an intransitive verb, 7 as a transitive verb, and 3 of what they term the essential meaning of the verb. Each of them is true to how we use the word in English. None touch upon how the rabbis understand the word.

אין עמידה אלא תפילה the Talmud declares, “there is no standing that is not praying.” Standing is praying say the sages. Prayer is an embodied practice that happens in relation to the world around us. It is an action rather than an introspection. The rabbis trace this Jewish practice back to this week’s parashah, where after Sodom and Gemorrah are destroyed and Lot’s wife turned to a pillar of salt we find the following verse:

וַיַּשְׁכֵּ֥ם אַבְרָהָ֖ם בַּבֹּ֑קֶר אֶ֨ל־הַמָּק֔וֹם אֲשֶׁר־עָ֥מַד שָׁ֖ם אֶת־פְּנֵ֥י יְהֹוָֽה׃

Early the next morning Abraham got up and returned to the place where he had stood before the Lord.

Truth be told, the Hebrew is more complex and interesting than this (and any other translation I found) expresses. Yes, Abraham woke up early the next morning, those are the first three words וַיַּשְׁכֵּ֥ם אַבְרָהָ֖ם בַּבֹּ֑קֶר. The next two, אֶ֨ל־הַמָּק֔וֹם mean “to the place.” So he woke up early to the place, which most interpreters agree means he went there quickly or went straight there. The next couplet אֲשֶׁר־עָ֥מַד means “in which he stood.” All of this the translation captures decently. But the final piece of the verse אֶת־פְּנֵ֥י יְהֹוָֽה׃ is untranslateable. The Hebrew word “et” from our phrase “Amad et peney Adonai” denotes a direct object. Literally this would be translated: “Where he stood the face of Adonai.” Standing is not a verb that takes a direct object. We stand on, before, up, to. Then what is the meaning of “standing the face of God?”

The commentators are silent on this phrase. They seem to see it as a type of phrasing that may have been prevalent during the time when Genesis was written, and that is comprehensible enough to us. It goes along with phrases like את האלוהים התהלך נח, Noah walked God, normally translated Noah walked with God.

In my view, however this line is too central to the way we pray today to ignore, and might hold some key to understanding what we mean when we use the word “prayer.” In the Talmud this verse is the proof text for the fact that Abraham created the practice of the morning prayer. When the Talmud uses the word Tefilah, prayer it is referring to the Amidah prayer – literally the Standing prayer, which is our central prayer in the morning, afternoon and evening service.

In a sense, whenever we pray the Amidah we are leaning on this instant in our collective imagination when Abraham “stood the face of Adonai.” What was the nature of his prayer? The clearest thing about it was that it was a dialogue. God says he’s going to destroy Sodom, and Abraham answers. They go back and forth, conversing with one another. The other clear thing about it is that Abraham does not stand God’s decision to destroy an entire city. “Abraham came forward and said, “Will You sweep away the righteous along with the wicked?” Abraham demands of God to act according to God’s job description; the righteous judge. “Far be it from You! Shall not the Judge of all the earth deal justly?” What follows is the well-known haggling over how many righteous people Abraham must find in order to spare the city.

Whenever we pray the Amidah we hearken back to challenging the ultimate authority, we stand up for what’s right, we demand goodness. In so doing we embody the face of God that we invoke when we speak the words of the priestly blessing: יאר יהוה פניו אליך, “May Adonai shine Her face toward you.”

It’s hard to stand up for something. When we do we often buckle under the pressure, or revert back to other things. But to stand in Hebrew also means to stop, as in the verse: “And the sea stood from its fury” (Jonah 1:15). Three times a day we are taught to cease what we are doing, to quit participating in the flaws of the world, the pressures of the particular ideology and culture of our time and place, and the fantastical rushing of our minds, to stand firm like a tree planted firmly in the middle of a gushing river. "Even if a snake is wrapped around your heel you should not interrupt your Amidah," says the Talmud. Remain standing, firm like a tree.

Prayer is stopping. Prayer is refusing to accept wrong. Prayer is reminding God and people and ourselves what we are all supposed to be.

Wishing you a peaceful Shabbat filled with sitting and lying down, and some standing as well.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Action as Beginning

by Rabbi Misha

Beginnings are important. How you set out will likely color the rest of your journey. In this week’s parashah the Jews begin, or rather the Hebrews, out of which the Jews will emerge.

Dear friends,

Beginnings are important. How you set out will likely color the rest of your journey. In this week’s parashah the Jews begin, or rather the Hebrews, out of which the Jews will emerge. If we judge this beginning from the first few words, it’s a marvelous one:

וַיֹּ֤אמֶר יְהֹוָה֙ אֶל־אַבְרָ֔ם לֶךְ־לְךָ֛ מֵאַרְצְךָ֥ וּמִמּֽוֹלַדְתְּךָ֖ וּמִבֵּ֣ית אָבִ֑יךָ אֶל־הָאָ֖רֶץ אֲשֶׁ֥ר אַרְאֶֽךָּ׃

Adonai said to Abram, “Go forth from your land, from your birthplace and from your father’s house to the land that I will show you.”

The actor is able to hear the primordial voice calling on him to begin a life that is his own. “The land,” the kabbalists tell us, is not physical. It’s a form of wisdom that will be cracked open and revealed to Abraham as his life unfolds. Our first ancestors had the ability to hear, to listen, and to set out in search of their unique path. This bodes well.

Quickly, though the journey sours.

Abraham, worried that his wife’s good looks will get him killed, convinces Sarah to be presented to the Pharaoh of Egypt as his sister, not his wife. The Pharaoh takes her in and sleeps with her (or is about to according to some of the commentators), and as a result gets a disease. Incredulous at Abraham’s lie he sends them away.

Shortly after Abraham complains to God that he has no child, and as such all of God’s promises of a nation that will sprout from him seem bogus. The rabbis point out that his prayer, while logical, is selfish. He could be praying for Sarah, or for the two of them. He could at least acknowledge her existence. Instead he lets his self-pity drive him and complains at God:

וְאָנֹכִ֖י הוֹלֵ֣ךְ עֲרִירִ֑י

I walk alone.

This is the line that leads right into the ugliest chapter in this beginning, the story of the birth of Abraham’s first child, Ishmael.

And Sarai said to Abram, “Look, YHVH has kept me from bearing. Consort with my maid; perhaps I shall have a son through her.” And Abram heeded Sarai’s request. So Sarai, Abram’s wife, took her maid, Hagar the Egyptian—after Abram had dwelt in the land of Canaan ten years—and gave her to her husband Abram as concubine. He cohabited with Hagar and she conceived; and when she saw that she had conceived, her mistress was lowered in her esteem. And Sarai said to Abram, “The wrong done me is your fault! I myself put my maid in your bosom; now that she sees that she is pregnant, I am lowered in her esteem. YHVH decide between you and me!”

Abram said to Sarai, “Your maid is in your hands. Deal with her as you think right.” Then Sarai tormented her, and she ran away from her.

God then steps in and protects Hagar, and makes big promises regarding her son to be. But I am more interested in the human behavior displayed, and so are several of the rabbis. Nachmanides writes:

“Our mother (Sarah) did indeed sin by this affliction, and Abraham also by his permitting her to do so.”

This is a courageous move from a major rabbinic voice. In most cases the commentators see it as their role to explain, defend and exult the actions of the ancestors. It takes the type of originality and guts that Abraham displayed in the beginning of the parashah for Nachmanides to speak out plainly in this fashion.

The medieval rabbi cannot ignore the reality around him. He sees Jews oppressed by their Muslim rulers all over the world. He sees strife between the seed of Isaac and the seed of Ishmael. So he continues:

“And so, G-d heard Hagar’s affliction and gave her a son who would be a wild-ass of a man (as God tells Hagar), to afflict the seed of Abraham and Sarah with all kinds of affliction.”

It’s a complex statement. On the one hand it paints Muslims as wild asses. And on the other it places the blame for the strife between Jews and Muslims squarely on the Jews. In any case we see a powerful attitude toward beginnings, rife with warning and possibility; How something begins is how it will continue.

Each of our actions is a beginning, and carries with it the weight of that which will come out of it. After all, we each have our own unique journey, hear our unique voices, make our unique mistakes and have the capacity to begin a unique tribe. We will all be shown the land that we must come to. On our way there let’s try to make our all of our beginnings openings to the unfolding of goodness.

I am feeling under the weather so unfortunately we will not be holding our Kabbalat Shabbat in person this evening. I hope you will meet me on Zoom instead.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

This is Torah Study

by Rabbi Misha

Hebrew school kicked off this week and it reminded me how fun it is to have conversations with young people about questions of spirituality and tradition.

Dear friends,

Hebrew school kicked off this week and it reminded me how fun it is to have conversations with young people about questions of spirituality and tradition. We sat in a circle and spoke the words of the Ashrei: we will praise you forever. I asked the kids about the notion of praising God and whether it makes sense to them. Answers differed as you might expect, but there was a general sense in the room that there is certainly something strange about praising God. I shared with them that when I was their age I didn’t understand why God would need my praise, or the praise of any human being, but that eventually I started seeing it differently, realizing that the praise we say is not for God but for us.

After learning a niggun we turned to the Torah. Naomi unwrapped it and Aliyah held The Yad in her hand, the pointer. When you introduce kids to a Torah scroll you sometimes realize what a crazy thing is. The scroll we were reading from was over 100 years old, and had survived the Holocaust in Romania, traveled to Israel in the 60s and then flew to Brooklyn at some point after that. It is identical or almost identical to almost every other Torah scroll in the world, including those that are written today. I watched as the kids touched the parchment and told me it felt like leather or paper or animal skin. Their eyes grew big when they were taught the labor went into this scroll, and goes into every one of these scrolls.

Finally we all chanted the blessing before the reading together and then Yoni chanted the first day of creation. “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. and the earth was formless an empty and darkness hovered over the surface of the deep.”

This is one of my favorite lines to teach. You can pause on pretty much any phrase and ask all kinds of questions. In the beginning. Of what I ask. What is this beginning? Is it a prolonged period or a moment? And what are our beginnings, as we start this new year? The question that came up with the kids this week was about that second verse. What does it mean that the earth was formless and empty? Did it exist or did it not exist ? is emptiness really empty and is formlessness not there? Aliyah said it’s a blob. June said it’s potential. Jacob said in any case it exists.When one goes slow she can scratch at what’s underneath these words. This is Torah study.

Then We chanted the blessing after the Torah together.

Later that week I met with Rami who has his bar mitzvah coming up in a month. As we were discussing his Torah portion suddenly he felt the need to share with me something: I don’t believe in God. Great, I said, but you know you’re going to have to speak to God at your bar mitzvah. When you say Baruch Atah Adonai, Blessed are you Adonai, what is it that you are going to be saying do you think? How can you construe those words to make sense for you? This is a question I often ask students who struggle with their belief in God, but really it’s a great question for theists to ask themselves as well. How can you re-construe ancient words to mean something for you? And specifically the recurring phrase Blessed are You Adonai. What might that mean to you today, and why actually are you saying it? For Ramy it had more to do with tradition, with his parents, but he also suggested something incredible: I’ll be saying goodbye to God. We ploughed that statement, imagined his future speakings of the same phrase, and wallowed in time for a moment. This is Torah study.

In our conversation about praise Daniel suggested that praise is easier once you’ve come out as a difficult situation. I shared with him that earlier that day I conducted a funeral, in which the family and I paused to consider the words we say when we hear of a loved one who has passed: Baruch Dayan Emet, Blessed is the Judge of truth. An amazing woman had lived an amazing life that she filled with beautiful creativity, questions, answers, movement and richness. Surrounding her casket where her seven grandchildren, walking her on her last way, And then singing her praises. That is also Torah study.

I very much look forward to seeing you at our first in person Kabbalat Shabbat next Friday at 630 on the roof of the 14th Street Y, or on Zoom if you can’t make it in person.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

A Beauty We Can Take Part In

by Rabbi Misha

The Torah is dead without us. It is a piece of dead animal skin with incomprehensible letters. Our job is to breathe the breath of life into it. We play God every time we read it.

Dear friends,

By the time we reached Neilah something had been transformed. One could sense the minds in the space were somehow softer, less busy, the bodies somehow lighter and the hearts sitting a touch closer to their original spot. I had experienced something like this toward the end of the day of Kippur before, but there was something special about this year. The density of fear, anxiety and instability all around us had something to do with it. The time we allowed ourselves to find where we are in the present moment also. The music, the ancient words, the coming together in person despite all the fears, and online despite screen-fatigue, the positivity and desire of each of us to create something together that comes out of our souls or kishkes or yearning or memories or hopes; these were the ingredients of our very special High Holidays services this year. On a personal note, these holidays were a far deeper experience for me in large part because I now know so many of you, whereas last year I was really just beginning to get to know you all. Thank you for being there with me, and for making these holidays so unique.

There were too many wonderful moments to recount, but to me the heart what happened this year were expressed by the two Torah readings, on the morning services of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. On Rosh Hashanah evening, in a Syrian piyyut we invoked God by the name Chai, meaning Life or Living, or Alive. This was the attempt in these experiential Torah readings, to make the experience of a Torah reading a living, breathing organism. My teacher, Rabbi Dovid Neiburg once likened the Torah to Adam’s lifeless body before God, in Genesis 2 blows the air of life into him:

וַיִּפַּ֥ח בְּאַפָּ֖יו נִשְׁמַ֣ת חַיִּ֑ים וַֽיְהִ֥י הָֽאָדָ֖ם לְנֶ֥פֶשׁ חַיָּֽה

G-d breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and Adam became a living being.

The Torah is dead without us. It is a piece of dead animal skin with incomprehensible letters. Our job is to breathe the breath of life into it. We play God every time we read it.

Many of you expressed your appreciation of the way we read Torah this year. How Amy chanted the Hebrew, Chanan sang the translation and Frank blew his horn to express the sensuality of the words and the emotions expressed. Some told me they heard it as if for the first time, much like the ancient Israelites in front of the Gate of Water in Jerusalem in 445 BC. I think we all felt that this was different, new, of the moment.

It strikes me as very much what The New Shul tries to do in general. An ancient tradition that can be so stale and remote can become fresh and exciting when we blow some of our breath into it.

It’s a similar process, I think with forgiveness. When we come to examine our actions, our patterns of behavior, our failures with the judgement of our idea of what should be, with rigid notions of right and wrong, we get lost in what is no longer alive. When, and this happened to me this Yom Kippur over the course of the day, we manage to extricate ourselves from the clutches of dead ideas and bring ourselves into what simply is, we know the complexity of each of our mistakes, the forces beyond us that lead us to make them, with some of them we even know they weren’t mistakes after all, but the unfolding of our lives. This softer type of judgement is the lounge of forgiveness.

Reaching this space is what allows for Sukkot to emerge. The holiday of joy, of nature, of gratitude for what has been harvested, of the beauty of the transitory. My grandmother, Deana z”l, who died on the eve of Sukkot almost a decade ago, taught me that this is the holiday on which we read the Book of Ecclesiastes.

אִם־יִמָּלְא֨וּ הֶעָבִ֥ים גֶּ֙שֶׁם֙ עַל־הָאָ֣רֶץ יָרִ֔יקוּ וְאִם־יִפּ֥וֹל עֵ֛ץ בַּדָּר֖וֹם וְאִ֣ם בַּצָּפ֑וֹן מְק֛וֹם שֶׁיִּפּ֥וֹל הָעֵ֖ץ שָׁ֥ם יְהֽוּא׃

When clouds fill with water

they empty themselves onto the earth.

And when a tree collapses down south or up north,

in the place where it falls, there it will lie.

We are a part of these cycles of life, filling and emptying like the clouds, arriving and departing in the spots that are ours. That is a beauty we can accept. That is a beauty we can take part in. That is a beauty we can love.

I look forward to celebrating Sukkot with you in an easy meditation walk in Prospect Park on Tuesday evening. If you’ve never done one before, it’s a chill, pleasant experience.

Chag sameach!

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Assignment Recap

by Rabbi Misha

It was beautiful kicking off the year with you. Many of you asked for a reminder of the assignment I gave to complete between now and Yom Kippur. This note will focus primarily on that.

Dear friends,

It was beautiful kicking off the year with you. Many of you asked for a reminder of the assignment I gave to complete between now and Yom Kippur. This note will focus primarily on that.

A week or so ago, when I was consulting with Holly about this very assignment she reminded me of that week of good will, that Et Ratzon that followed the September 11th terrorist attack. We recalled together how the entire city was washed over with positivity and warmth in the face of the disaster. We remembered the impossibly long lines to donate blood, the people helping one another on the streets, strangers sitting together on stoops; an active community of millions. During that horrific moment we found a way to act, for one another, for goodness. That is the action that Hannah Arendt defines as freedom, and what I am suggesting we search for this week.

The question at the heart of the assignment is what can we do with what we’ve learned? What can we do in this world that is so cracked, despite our limited capacity?

This past year we’ve all learned things about how to better live our lives. Think back and reconstruct those lessons. They could be lessons you’ve learned about your own life, your family unit’s, your city or society at large. They could be lessons you learned because you had a different angle or more space to think, or they could be lessons thrust upon you by the trying circumstances you were in. However you reached these understandings, see if you can find a small way to realize one of these lessons, to pass it forward.

On Monday night I conjured Hannah Arendt and her idea of action, which must involve other people, and cannot be solitudinous. So you want to look for a way to actualize what you’ve learned that isn’t only for yourself.

One way to think about it that might be helpful would be to ask yourself what helped you this past year, and then to pass that outward. If, for example, a friend’s phone calls helped keep you happy you might think of a person that would perhaps be lifted by a phone call, and call them. Maybe a physical activity like sports or yoga helped you, and there’s someone you know who might get a boost from some yoga classes or a session with a personal trainer or whatever activity it is. Maybe you learned that music is important to you, and you can send some people a song or two, or invite them to listen to some music together, or send them to a concert. Maybe a random kind act that someone did for you stayed with you and you want to make a meal for a homeless person, or volunteer somewhere. Many of us sensed a major change in our internal landscape after the elections. Maybe there’s an election you can make calls toward, or text out the vote or volunteer on some particular issue. Maybe you discovered Shabbat this year and want to invite someone over for dinner on a Friday night soon.

It doesn’t have to be a big action. My hope is that it will help us define one of the lessons we’ve learned, and that it will allow us to step beyond our doubts and to do a small deed of goodness, as a way to express our gratitude for what we have learned. Maybe it will move us one step toward knowing that God is good, that the world is good, that we are good, that despite all the difficulties, goodness abounds.

I look forward to hearing about your thoughts and actions on Yom Kippur during the morning service.

I also want to remind you to bring cloths of any kind to weave into our collective standing loom, which Suzanne Tick so beautifully described on Monday. This will be an opportunity to literally weave our community’s intentions and prayers for the new year together in the way this Shul knows best: through art. You can cut them up into strips, or just bring them in as they are for whichever service you can attend on Yom Kippur, and we will have scissors and markers there in case you’d like to write a word or a prayer onto the cloth.

May this shabbat bring us the peace that will move us to action.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

New Year New City New Shul

by Rabbi Misha

I arrive at this new year wet, slightly ragged, but infused with new ideas and horizons I’ve picked up at our chevrutahs this last month. I come with a real feeling that I need to see you people, that we all need these holidays, that being together in whatever way each of us is able will give us the boost we need to dive into this year.

Dear friends,

I arrive at this new year wet, slightly ragged, but infused with new ideas and horizons I’ve picked up at our chevrutahs this last month. I come with a real feeling that I need to see you people, that we all need these holidays, that being together in whatever way each of us is able will give us the boost we need to dive into this year.

Yesterday morning on the subway platform I saw a woman singing I Will Survive to the tiny number of people who braved the post Ida MTA. She reminded me that I love this city. Strange and beautiful acts of resilience and resistance happen here. Unusual and interesting entities like The New Shul mushroom out of the fertile asphalt. Moments of beauty are less rare here and pop up when you’re not expecting them.

Rosh Hashanah last year, in a farm in Queens produced that feeling too. I was just finishing the Amidah when Liat showed me a headline on her phone. “Ruth Bader Ginsburg is dead.” When we got to the mourners Kaddish people yelled out her name. We gasped. Some cried. The musicians played their music. And then community members shared their cooked pieces of glory that represented what we needed in that moment. Ghiora explained the details of his saffron honey cake, a complex kabbalistic creation with specific numbers of nuts to reflect the zeitgeist. Others shared their fun brilliance in the form of cooked goods. And the moment was transformed. We were still sad, but we were in community, and it was nice. The bitter shock had softened a touch.

Theater for the New City, where we will meet on Monday evening is a historic place. Early Sam Shepard plays, Living Theatre performances that changed the definition of what a play is, the wildest Halloween costume party in the city for years on end, Street plays to protest Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, Bread and Puppet Theater performances protesting the ills of capitalism and hailing the indestructible power of Mother Earth, Grammy and Emmy and Pulitzer prize winners work performed before anyone knew who they were. Fifty years of New York strange, New York protest, New York art - and now we step into the fold, and try to cook up some New York Shul action.

The chevrutah learning pods over the last month proved to me yet again what a unique group of people this Shul is made of. The type of discussions that went down in the Erich Gutkind chevrutah, a strange and marvelous combination of philosophy, rebellion and mysticism, were something I hadn’t experienced in a long time. In the Death and Dying chevrutah, deeply personal reflections on loved ones was shared in a way I had never quite witnessed, combining intellectual digging into text with the quiet awe of knowing there is an end. In the Karma chevrutah there were discussions of past lives. In Nehemiah history and economics morphed into the present political moment and Kabbalah. In the Meditation and Niggunim chevrutahs gates were opened, hearts relaxed, people shared moments of peace.

Despite what we may or not be feeling, we are ready to bring in a new year together.

See you Monday evening at Theater for the New City, and Tuesday morning at Brooklyn Bridge Park. (If you haven't already please register!)

Let’s use these last few days to prepare. Our season of return begins.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Our High Holidays Plans

by Rabbi Misha

This Shabbat, stop and remind yourself that the holidays are coming. A new type of Beginning is returning to our city and our hearts.

Dear friends,

We have been in touch with many of you about the specifics of our High Holiday plans with regard to Covid. Some of you have reached out with questions or concerns, others we have contacted to consult with or ask how you and yours are feeling about in person gatherings, especially indoors. Susan, the Va'ad and I have been deep in these questions for at least several weeks. And I wanted to share with you all where we have landed and why. I can’t think of a more important communication at this moment.

Last Yom Kippur we read the following words from Deuteronomy: “I have given you today life and goodness, death and evil. Choose life.” That’s what we are working on. What does choosing life mean for us this year? Our highest priority is our health, first physical and then mental. People need in person services more than ever. But not all of us feel comfortable attending them at this stage of the Delta’s spread. The vast majority of adults in our community are vaccinated. But all our kids under 12 are not. They and their parents are pretty tired of getting tested every two minutes. And we all understand what’s at stake, and are accustomed to the sacrifices we each have to make for each other these days.

We think we have come up with a plan that maximizes everyone’s ability to participate with joy and ease this year. It’s not perfect, or full proof, but health experts we’ve spoken to have backed us up and we believe we will be all be able, in one way or another to feel the unique New Shul jig moving through us.

Besides all services being streamed live on Zoom with a top notch team of video and sound crew, we have moved some of our services outdoors. On Rosh Hashanah two of our three services will be by the water, morning service on Tuesday at Brooklyn Bridge Park and afternoon Tashlich on Wednesday. We hope this will make it possible for some who aren’t comfortable coming indoors to join and to make it more family friendly (both outdoor services will be shorter, more experiential and near a playground for jumpy ones). We are considering moving one of the Yom Kippur services outdoors as well.

The indoor services will take place in a huge theater (Theater for the New City on 1st Avenue and 10th Street), with very high ceilings, two windows, and an air filtration system recently revamped to Equity’s high standard. We will be capping capacity at 50%, but expect closer to 20% for all services except Kol Nidrei. Entrance will require proof of vaccination for those 12 and up, and a negative PCR test for those under 12. We will be wearing masks and maintaining social distance. For many months no one has been allowed into the theater without proof of vaccine or a negative test due to their strict policies.

A week ago our incredible team of designers and tech crew met at the theater. The meeting got us all excited. Not only did the artistic vibe of TNS display itself in exciting ideas, but the team was so impressed with the theaters safety protocol that some who weren’t planning on coming in person decided to come after all.

None of this is a guarantee of any sort. We go into these high holidays with awe and unknowing. But the Va'ad and the leadership team feel confident that we will be safe - as medical consultants have told us - that our plan answers as many of our community’s needs as we possibly can at the moment - that this is our way this year to choose life.

If you have questions about any of the particulars of our Covid plans, please reach out to Susan at Susan@newshul.org. If you would like to come but are unsure, and feel like talking it over would be helpful, please call me at 9172020882. I will happily listen and certainly won’t pressure anyone one way or another. We all need to speak through our feelings every now and then. I am here to talk over this or other joys and sorrows. Elul is a heavy month always. Lots of us are struggling these days, and these holidays can help us work on ourselves. We want to use these opportunities in the way that makes most sense for each of us.

If you haven’t already, please let us know your plans for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. Wherever you join us from, it’s going to be an awesome ride.

This Shabbat, stop and remind yourself that the holidays are coming. A new type of Beginning is returning to our city and our hearts.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Return Return Return

by Rabbi Misha

But how does one begin the process of teshuvah, return? We are clouded by our circumstances, our suffering, our patterns of behavior, our ideas of what we want and need. Reaching that clear perception of truth is hard. Where might we start?

Dear friends,

Every day we pray for return. We remind ourselves that God wants us to improve, that we want to be better, that the self we have grown alienated from is calling us back. In the prayers of this season, which culminate in Yom Kippur, we keep repeating the mantra:

Adonai Adonai, el rahum vechanun, erekh apayim verav chesed ve’emet, noseh chesed la’alafim noseh avon vafesha vechata’ah venakeh.

“Adonai! Adonai! God, Compassionate and Gracious, Slow to anger and Abundant in Kindness and Truth, Preserver of kindness for thousands of generations, Forgiver of iniquity, willful sin, and error, Cleanser of all.”

The mantra works as a reminder that we, like God, are capable of compassion, of forgiveness, of return. It reminds us that return is always available to us. It is, as philosopher Erich Gutkind suggested, “a perpetual possibility.” After all, Gutkind wrote, the state we wish to return to, that of “a clairvoyant perception of truth,” is a human faculty that each of us possess, “like eyes and heart.”

But how does one begin the process of teshuvah, return? We are clouded by our circumstances, our suffering, our patterns of behavior, our ideas of what we want and need. Reaching that clear perception of truth is hard. Where might we start?

In our meditation chevrutah this week two answers were offered. The first avenue was the senses. We sat and noticed what we hear, smell and see. Without judgement or even thought if we can, we simply observed. Over and over we returned from our wandering panting minds to the simple reality we are in. In the next exercise we worked on the breath. Return to the breath. “Return, return, return,” Michael guided us. If we are able to create small islands of presence, with them may come the islands of peace that will help us step out of our spirals and anxieties, and come back to ourselves. When I listened to the sounds, I heard the cicada’s for the first time this summer. At that moment I knew for a minute that I am in and a part of the cycle of nature, that everything is in its right place, including me. I became aware of the greater reality I live in. I returned home to the world.

That kind of awareness can be painful. When Nehemiah receives a report from his brother about the ruinous state of affairs in Jerusalem, his and our spiritual home, “the city where my ancestors are buried,” as he names it, he breaks down. For days he fasts, prays and self-examines. He works hard to admit his wrongs, to pull himself back to a place where he might be able to do something about the situation that is breaking his heart.

“Lord, the God of heaven, the great and awesome God, who keeps his covenant of love with those who love him and keep his commandments, let your ear be attentive and your eyes open to hear the prayer your servant is praying before you day and night for your servants, the people of Israel. I confess the sins we Israelites, including myself and my father’s family, have committed against you. We have acted very wickedly toward you. We have not obeyed the commands, decrees and laws you gave your servant Moses.”

A few weeks ago we learned that mindfulness in the Buddhist tradition is infused with memory. And indeed a crucial piece of his return has to do with memory.

“Remember the instruction you gave your servant Moses, saying, ‘if you return to me then even if your exiled people are at the farthest horizon, I will gather them from there and bring them to the place I have chosen as a dwelling for my Name.’”

He is speaking to God, or to himself. He is gathering courage to believe in the possibility of a better world, a stronger self, a rebuilt Zion, a home that isn’t broken.