Sort by Category

Religion in Technicolor

by Rabbi Misha

Every spring, exactly one week before Passover a unique ritual takes place in the South of India. The local Jews leave their towns, cities and villages, and make pilgrimage to a small, holy mountain tucked away to the east of the backwaters.

A different kind of holiday celebration at the School for Creative Judaism

Dear friends,

Every spring, exactly one week before Passover a unique ritual takes place in the South of India. The local Jews leave their towns, cities and villages, and make pilgrimage to a small, holy mountain tucked away to the east of the backwaters. As the sun sets, they climb the 1800 steps that lead up to the mountaintop shrine, where they gather to watch the play that they have seen every year since their birth. It depicts the Pharaoh of Egypt’s struggle to understand how he brought about the death of his first-born son in the tenth plague.

After lighting the ritual flames, they watch him tell the story we all know of the Hebrew slaves’ leader Moses, and the ten plagues he brought upon Egypt in order to secure their release from slavery. They hear Pharaoh’s reasoning for refusing to let the Hebrews go and watch him turn from an all-powerful god-king to a sad, broken father. And then they walk down the mountain singing a psalm of humility.

They have felt the pain of their enemies. They have witnessed the consequences of their fight for freedom. They have internalized their adversary’s perspective. They have shed a layer of certainty and gained a layer of understanding.

Now they are ready to celebrate Passover.

There is no lost Jewish tribe of South India that performs this ritual. I made it up when I sat down this week to write my playwright's note for my play, PHARAOH. But what if there were such a tribe with that ritual? What if this were a tradition right here in New York City, which would take place at the highest point in Fort Tryon Park, or on Mount Prospect Park, or up the river over the Hudson? How would it change our experience of Passover? Our relationship with liberation? What would the inclusion of a ritual play in our religious practices do to our experience of our faith tradition? What would preparing for Passover by diving into the inner world of Pharaoh do to our national psyche and our political behavior in the world?

It has always seemed to me, and I’m oversimplifying here, that Jews have a hard time imagining the Palestinian experience. “There is no Palestinian people,” they would tell me as a kid, even as I would see people hanging up a Palestinian flag on the lamppost beyond the fence of my elementary school in Jerusalem. I was never taught anything about the history and culture of those we shared the land with. They were often represented simply as terrorists. There was an incredible flattening of the humanity and the culture of our neighbors.

The story of the telling of the exodus is not dissimilar. We grow up with a stick figure cruel king who kept saying "No, no, no," for no reason whenever the Hebrew freedom fighter would ask him to let the slaves go. That's not far from how the Haggadah tells it too.

The Torah, however gives a richer depiction of Pharaoh. in several interactions he listens quite carefully to Moses, and makes him offers that seem like they should satisfy his requests. "חטאתי ליהוה," the king even says to Moses a few plagues in, "I have sinned to YHVH." Is that not at least the beginning of a repentance process?

Furthermore, the king of Egypt offers perhaps the thorniest problem regarding free will in the entire Torah. Over and over again we are told that "YHVH hardened Pharaoh's heart." It appears so many times that the commentators have to excuse this breach of human freedom - upon which the entire belief system is founded! - with the excuse that God only hardened Pharaoh's already hard heart. Not only is this a weak excuse, but it also negates a prime principle of rabbinic biblical exegesis, that every word in the Torah is exactly right, and holds both straightforward and deeper meanings. The matter serves to further enrich the king's character, who appears to be moved to denying the Hebrew's demands by God, rather than his own impulse.

The Torah, in other words, offers us a nuanced character, Since then, this biblical character has been systematically flattened into the one that appears in our children's songs, out of a human desire for simplicity. We seem to be wired to need black and white in order to function. But that is precisely what creates a colorless reality.

PHARAOH, which opens a week from today was the play I wrote as my main project toward becoming a rabbi. I wrote it as a rejection of the black and white that led us to October 7th, as well as October 8th through today; a rejection of the knee-jerk vilification of those we disagree with; and an invitation to recreate our ancient faith traditions as complex, forward-looking frames, through which we can see all the colors of the rainbow.

I hope you can join us this evening for a colorful New Shul Shabbat of Peace, which will include an array of incredibly talented Broadway singers and musicians, freedom songs by the inimitable Rob Kaufelt and prayers for a better world.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

One (and only?)

by Rabbi Misha

Before I begin, I'd like to invite you all to a very special gathering we're holding this evening, which can connect us to both the reality of the current situation in Israel/Palestine, and the hopeful ways people are working to overcome it.

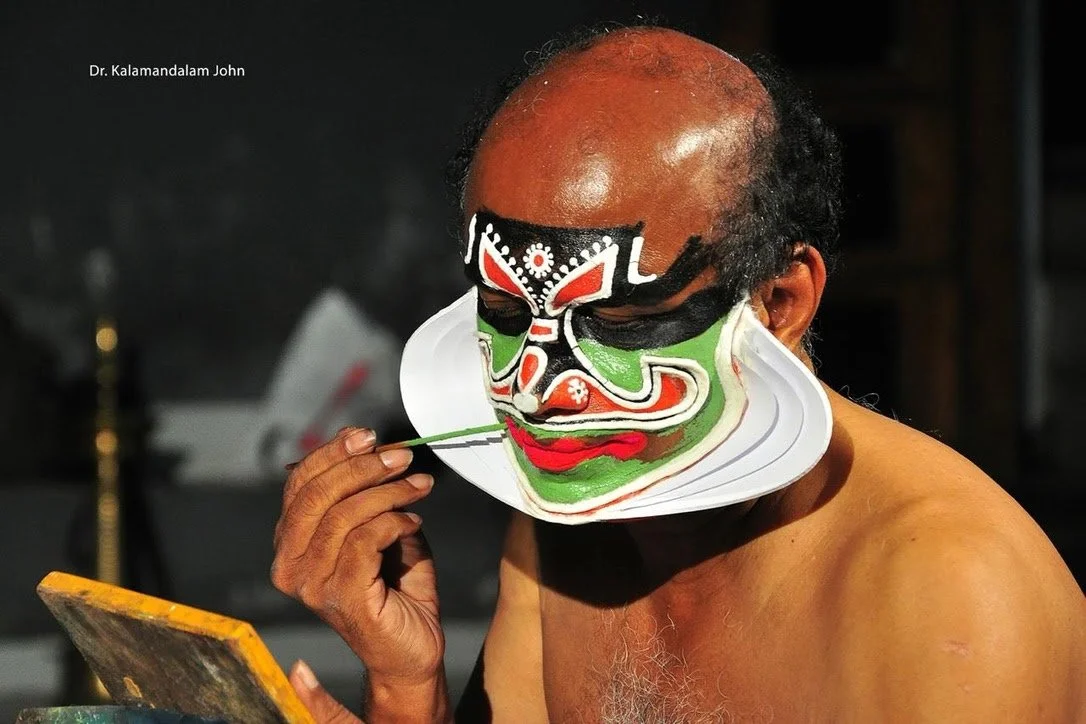

Kalamandalam John

Dear friends,

Before I begin, I'd like to invite you all to a very special gathering we're holding this evening, which can connect us to both the reality of the current situation in Israel/Palestine, and the hopeful ways people are working to overcome it. Spirit of the Galilee is an important organization working on co-existence between different faiths and cultural groups in the north of Israel. We will be joined by Ghadir Haney, a renowned and highly influential Muslim social activist, from the city of Acre, Fr. Saba Haj, the leader of a 5,000-member Christian-Arab-Orthodox Church in the town of Iblin, and Rabbi Or Zohar, Reform Rabbi of the Misgav region and director of the Spirit of the Galilee Association (SOG). These are critical voices for us to hear and take in here in the US, and I hope you can all join in person or tune in.

And now I'll pick it up from where I left off last week.

When he was fifteen years old, John was living a perfectly normal life for a Christian teenager in the South Indian state of Kerala. He went to the local school, and to the nearby Orthodox church for religious instruction . And then something happened that radically changed his life. He went to the theater.

Kerala is home to two of the oldest existing theatrical traditions in the world, which are kept as national treasures, but watched by very small audiences. Kudiyatam is the slower and more drama oriented form, in which a play lasts between 9 and 43 nights, each night between 2-5 hours. Kathakali is a form of dance theater with a faster pace, resulting in plays that only last one full night. At fifteen, John witnessed the latter and immediately fell in love. It did not matter to him that Kathakali tells only the stories of the Hindu gods from the great epics, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. Nor did it matter that most performances took place in Hindu temples, and included the actors paying obeisance to the temple gods. John left his school and his church education and devoted himself entirely to becoming a Kathakali actor.

For 9 years he studied the ins and outs of the form, at the prime school for Kathakali, the Kerala Kalamandalam. The full day, physically demanding days teach the actors techniques of controlling each part of their bodies, from head to toe. Mornings begin with eye exercises, continue with the study of abhinaya, the unique sign language used in Kathakali and Kudiyatam, and end with rigorous dancing. When he graduated, John was awarded an excellence award, and became the world’s first ever Christian Kathakali actor, and was awarded the honorific Kalamandalam John.He performed the Hindu plays for many years. When the opportunity presented itself he created a Kathakali play about the Christian saint who first came to the region from Syria. Despite controversy, he performed the saint without the elaborate make up and costume, in a simple monk’s outfit.

His wife Marie also shook things up in the Kathakali world, when she learned the art of Kathakali make up and began to prepare John for performances, (as you can see in the picture above) a process which takes three hours. She is the first and only Indian woman Kathakali make up artist.

John exhibits two things that impress me deeply, beyond the incredible talent and knowledge that come with 50 years of performing and teaching Kathakali. The first is a rare openness to experimentation and new creations, which remains rooted in this ancient theatrical form. And the other is the deep-seated openness around divinity that I have only witnessed in India. How could a devout Christian pay obeisance to Siva, Rama, Brahma, Vishnu or any of the other Hindu gods? How could he participate in a play written by a rabbi who considers the performance an offering to God? Because God is one.

The old Indian way is welcoming and inclusive of any and all gods. “Who, Jesus? Sure! Bring him into the temple! Adonai you said? An invisible god? Great, let’s put one of his symbols next to Ganesh.” This welcoming multiplicity comes from a deep understanding that God is simultaneously the most serious business we have, and a manifestation of human play. It’s so real that it goes beyond the categories we habitually use for reality. Using God to exclude or denigrate others is the ugliest type of idol worship.

My play, Pharaoh is in part an attempt to define what we mean by the phrase “one god.”

“What does it mean when you say ‘one and only God,’” Pharaoh asks Moses in one scene. After Moses scoffs at the question Pharaoh digs further: "So you're saying that everything we Egyptians believe in is a......"

"Fantasy," Moses answers.

This absurdly vain idea, that my imagining of God negates yours, has been bugging me since the first time I ever stepped into a Hindu temple, and was slapped with my people's centuries of guilt and prohibitions. I was sixteen and vulnerable to such guilt trips. And yet I quickly began to see how that exclusionary vision is being used not only for religious and cultural reasons, but for political purposes, with dire consequences.

Both monotheistic and polytheistic traditions can be either inclusive or exclusive, depending on your interpretation of the core idea of godliness in them. The current Indian government is taking an inclusive and playful faith tradition, and twisting it to exclude and humiliate Muslims and other faiths. Some Christians, Muslims and Jews around the world sin by interpreting the notion of one god as an exclusive and punishing “truth.” The faith I live by is a monotheism that is not threatened by other gods or notions of divinity, but raised up and buoyed by them. “Adonai Echad,” "God is one," means we are all one, a part of the all. The idea that “only my god is real” is, to my mind the opposite of the Torah’s charge.

Today, when John inhabits a character, he is in a glorious and unified command of his body. A decade of rigorous training followed by four decades of performing and teaching all over the world manifest in the spectator’s sense of watching a master at work. Countless times in rehearsal, Michael, Alysia and me have been swept into wonder watching John bring Pharaoh to life through movement.

Let us all take a page from Dr. Kalamandalam John in bringing true glory to God, through the open creativity, playfulness and inclusive understanding of the concept of God, and its expression through the wonder of the human body.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Pharaoh Sends Love

by Rabbi Misha

It has been fifteen years since I began obsessing over Pharaoh. It began in a tiny village in the south of India, a lush, tropical heaven by a river, where I had come to watch a play. It was a little longer than most plays I had seen with a run time of just over two weeks.

Chakyar Margi Mahdu as Ravana in the Asokavanikangam. Photo by Ranjith S

Dear friends,

It has been fifteen years since I began obsessing over Pharaoh. It began in a tiny village in the south of India, a lush, tropical heaven by a river, where I had come to watch a play. It was a little longer than most plays I had seen with a run time of just over two weeks. Every evening we would gather at the Kuttambalam, a small, roofed open air theater a couple minutes walk from the temple. The drummers would take their seat atop the giant mizhavu drums, a conch horn was blown, and the actor would appear onstage, in the elaborate costume and make up of the ten-headed demon king, Ravana. That is when the improvisation would begin. Using the unique sign language of the Kudiyatam theatrical tradition, he would remind us what happened yesterday, and then enact for us the next piece of the story, complete with hours-long diversions to paint the full picture of the associations and memories the story evokes in Ravana’s gorgeous mind. It might go on four hours. Usually a bit less, sometimes more.

The play was called the Asokavanikangam, or Asoka Tree Garden, and told of the time when Ravana kidnapped the goddess Sita, wife of Rama, and did everything he could think of to convince her to sleep with him. It didn’t work. Ravana was thrown into a crisis. Never before had he been prevented from accomplishing a task, fulfilling a desire. Several times during the course of the play he recalls the time when his charioteer told him they would have to travel around Mount Everest (called Kailasa in the play), because it’s too high to go over. Ravana refused to accept this indignity. He steps off the chariot, and though it might take him half an hour of stage time he eventually succeeds in picking up the mountain and moving it aside (not before some agile juggling). Now, however, he is faced with an obstacle he cannot surpass, in the form of Sita’s pure devotion to her husband.

Over the fifteen nights of the play we watched Ravana lose his powerful, charismatic self to the experience of limitation. While he would sit sadly on the floor reckoning with his inability and his tremendous lust, the theater would be visited by fruit bats, who would fly in and flatten themselves against the ripening bananas decorating each side of the stage.

This is what religion is meant to be. An encounter with human creativity, with joint brokenness, with the interconnected depths of good and evil, with the inconceivable beauty of life.

I came out of that experience with two convictions, one conscious and the other not yet. Consciously I decided to write a play that would offer the gift of falling in love with a mythical villain to a Western audience. A few days later I landed on the great enemy of the Hebrews, symbol of ego, stubbornness and cruelty to all three major monotheistic faiths, Pharaoh. The next day I arrived at the central temple of the great ancient Tamil city of Tanjavur. After offering gifts and prayers to the god Siva and his bull Nandi, I parked myself with a notebook in a corner of the temple, and out came the first scene, where Pharaoh battles Death, and wins.

Since then I have been spending far too much time with my beloved Pharaoh. I have learned of his genius, his relationships with his wife, daughter and son, his blind spots and his prophetic wisdom. I gained insight into the theological-political duel between him and Moses. I have come to see the destructiveness in the flat story of good and evil that our tradition attempts to maintain. And I’ve encountered through him my own hints of divinity, and my deep, human limitations.

After a path I could have never imagined, the play is set to open in a few weeks, with a South Indian master of Kathakali - the faster paced dance theater sibling of Kudiyatam - in the lead role, who will be dressed in the same costume and make up as Ravana was in that play I saw all those years ago. I’ll tell you more about this incredible actor and maybe more about the theological battle at the heart of the play in the coming weeks. And hopefully about that unconscious conviction I mentioned earlier as well. It’s rare for a playwright to have an opportunity to lay out the story of writing the play, and the ideas they are working out in them. I’m excited to take these next few weeks until the opening to dig into some of the driving questions behind my rabbinical and theatrical path, as they found expression in the writing, acting and production of Pharaoh.

For now I wish you a peaceful Shabbat. Pharaoh sends his love. Might it be time to open your heart to him?

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

The Angel in Your Dream

by Rabbi Misha

One of the greatest polemical books in the Jewish canon is The Kuzari, a medieval book by Rabbi Yehudah Halevi. The book tells of the idol-worshipping King of Kuzar, who has a recurring dream, in which he is visited by an angel who tells him:

Dear friends,

One of the greatest polemical books in the Jewish canon is The Kuzari, a medieval book by Rabbi Yehudah Halevi. The book tells of the idol-worshipping King of Kuzar, who has a recurring dream, in which he is visited by an angel who tells him:

כוונתך רצויה אך מעשך אינו רצוי

Your intentions are desired, but your actions are not desired.

The king understands that God is both pleased and displeased with him. He must keep his intentions of serving God, but change the ways in which he does it. The king then engages in philosophical, religious and theological conversations with a philosopher, a priest, an Imam and a rabbi, in an attempt to figure out which practice he should adopt.

At the heart of the book is a challenge to us all: can we ask ourselves the question posed by the angel. Where are our intentions good, but our actions not?

The question seems to me the stuff of dreams. Something that can gnaw at our subconscious at night and unnerve our days. But there have been times in my life, in which I've managed to locate a discrepancy between action and intention, moments in which I was telling myself I am doing one thing, but in effect doing another. During those times it is as if my body is serving someone else. And perhaps the strangest thing about it is that while it does that, buried in the back of my own mind is the full knowledge that this is taking place; that I am setting aside the connection between my mind and my body for a time, and living with the pain of that split.

Last week I related some of my military service, and several of you expressed interest in that experience. In my own limited conscious understanding of my self, there is no other experience I've been through that better embodies the angel's axiom about intention and action. The intention was to give back to the collective, to do my part, to protect life, to participate in the shaping of our world. The action was to uphold an occupation of a militaristic nation state.

People really do want to do good. I believe that about almost every person. I believe that about myself, and I believe that about you. But I know that our actions don't always result in goodness. The angel asks: Where are we not acting out our true selves? Where are our intentions taken hostage by someone else's agenda? Where are we supporting causes and projects that bring about our internal corruption or our national combustion? Where are we living someone else's life?

If we can find those places we might be able to unclog the channels between our pure intentions and our misguided actions.

If we can pose these questions to our waking, and more importantly perhaps to our dreaming selves, maybe we will be able to enjoy the deep satisfaction of having both our intentions and our actions desired by that mysterious force who keeps consciousness flowing.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Happiness in Tough Times

by Rabbi Misha

I always remembered my time in the Israeli army as depressing.

Living Theatre legend, Tom Walker, who died last week, performing a strike-support play with the company in Italy, 1976

Dear friends,

I always remembered my time in the Israeli army as depressing. Beyond the fact that soldiers are constantly counting backwards the days until they go home, and until their final release, I felt my time in the South of Lebanon as a moral compromise about which I was deeply conflicted. The idea of being a part of any army felt antithetical to who I am. And following the orders of the terrible and cruel man at the top of the pyramid – then first term Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu - didn’t help. Imagine holding a rifle that you have to shoot whenever the leader you hate most says shoot and you’ll understand the situation I was in.

Soldiers were dying around me, while rockets kept flying into northern Israel, the stated reason for our presence there. More depressing was the state of the local population, with which I had significant contact, since my base in Marj Ayoun served as the regional headquarters of both the IDF and the South Lebanon Army, a kind of puppet army of Israel. The locals had no prospects, between the allegiance they had to show the IDF to survive, and the knowledge that one day the Israelis will leave, and Hezbollah will take over and accuse them of collaboration with the enemy. I left in 1999, and indeed a year later that’s exactly what happened.

A few years after I was released, I visited my commanding officer, long out of the army, and like me pursuing a career in theater. Sitting in his apartment in Jerusalem, he showed me a photo from our service. Five of us were in his office in our uniforms, each of us with smiles on our faces. Mine was the biggest smile in the photo. The photo rattled me. It brought back the experience of the day to day there, the friends I hung out with, the exciting sense of moving around, hitchhiking up to the northern border, bussing down to see my girlfriend in her kibbutz near Haifa, reading Hemingway under the sole fig tree in the base, drinking Lebanese black coffee (rivaled only by Italian espresso in Italy) as I gaze out at the high mountains leading up to Syria in the east, and the Beaufort, a majestic Crusader fort above the Litani Valley to the west. That single photo shattered my conception of my time in the army. I saw it and knew that even within the painful circumstances, I had plenty of moments of happiness and contentment.

I find myself wandering back to that time in search of ways to be content during this period. The war rages on. The insanity of the death toll and the destruction of Gaza weighs heavy. The hostages that are still alive are not back. And that’s before I even go into my more mundane anxieties and painful events here in New York. Anyways this stage of winter has a way of getting me down.

And yet – this evening begins a new moon.

This moon of the Hebrew month of Adar brings with it a command:

משנכנס אדר מרבין בשמחה,

“Once Adar begins, we do lots of happy.”

More than that, this is a leap year in the Hebrew calendar, which means we get two months of Adar. Do you feel that kick in your ass to step out of your malaise? Those are your ancestors saying “snap out of it! Life is short.” It’s time for us to actively seek happiness, relaxation, peace. We deserve it.

Shortly after I came out of the army and engulfed myself in the New York downtown arts scene, I met a theater troupe that had just come back from a series of workshops in Lebanon. When they were down south, in what was by then Hezbollah territory, they created an anti-war play in the notorious Al Hayyam prison, where the IDF would imprison and often torture suspects. Led by the daughter of a rabbi, The Living Theatre is a pacifist-anarchist group that was in the business of taking the brokenness of the world and the pain in their souls and transforming it into borderless, theatrical love. My years with the company taught me a lesson about joy: it’s not about ignoring pain; it’s not about ignoring the world; it’s not about ignoring what you feel commanded to do. Be with it, and see through it into God, into humanity, into the dancing soul of the universe.

I hope you can all join us this evening for Shabbat, where we will follow the tradition of finding joy on the narrow bridge. John Murchison, a wonderful Qanun player will be joining Yonatan and Daphna in bringing the music, and rabbi and activist Miriam Grossman will join me in laying out the ideas that might lead us to finding happiness and peace.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Jazz Shabbat 2024

Jazz Shabbat 2024

Our Jazz Shabbat at The National Jazz Museum in Harlem on January 19.

Nothing on My Tongue

by Rabbi Misha

Imagine the world going silent.

Dear friends,

Imagine the world going silent.

Perhaps the last time such a moment took place was 3,334 years ago (according to Rabbinic calculations.) That was when our people stood at the foot of Mount Sinai, as described in this week’s parashah, and expounded upon ever since.

“When the Holy Blessed One gave the Torah no songbird chirped, no winged creature took flight, no cow mood, no angel flew, no seraph said “holy!” The sea did not move, the people did not speak, but the world is quietly keeping silent – and the voice came out: “I am YHVH your God.”

Without keeping silent, we learn, revelation would not have come. Keeping silent is an old virtue that could use some reviving. So much of our anguish and anger these days come from people's inability to measure their words.

“Rabban Shimon Ben Gamliel said: All my days I grew up among the sages, and I did not find anything as good for the body as silence: and anyone who speaks too much brings about sin.”

The silence that took over the world before the utterance of the first of the Ten Commandments (or in Hebrew the Ten Dibrot, or spoken pronouncements), allowed for the word of God to be heard in all of its precision and power. It imbued the words that came out with a transcendence of time and space.

The rabbis succumb to their poetic instincts:

“Every single word that came out of the mouth of the Holy Blessed One filled the entire world with the smell of sweet spices.”

“Every single word that came out of the mouth of the Holy Blessed One split into seventy languages.”

“When the Holy Blessed One gave the Torah to Israel His voice went from one end of the world to the other, and the kings of all the nations were taken over by trembling, and they began to sing.”

And yet, precise words that come after true silence can be dangerously strong.

“Every single word that came out of the mouth of the Holy Blessed One made the souls of Israel depart.”

In other words, when the Hebrews heard God’s voice, they all died! Then how did we receive this story, you might ask.

“The word came back in front of the Holy Blessed One and said: Master of the world, you’re alive and your Torah is alive – but you sent me to dead people?! - They’re all dead!

The angels began to hug and kiss them. “Don’t worry, you are children of YHVH!” And the Holy Blessed One sweetened the word in His mouth and said to them: are you not my children? I love you! And continued to touch them until their souls returned.”

That word travelled all the way to the end of the world and right up to its source.

This is the power of a word preceded by silence. Not only can it kill, but it can also give life, as the Book of Proverbs put it:

מוות וחיים ביד הלשון

“Death and life are in the hand of the tongue.”

At our Kabbalat Shabbat next Friday we will be transported by the Qanun of our musical guest, John Murchison to that prayerful realm of “nothing on my tongue but Hallelujah,” as Leonard Cohen described it. Until then, let us all practice staying silent, and maybe allowing the few precise words that follow to emerge.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

A Happy Story

by Rabbi Misha

A happy story is set to reach its climax tonight in my neighborhood in Brooklyn. You’re all invited, and it’s worth accepting and taking the Q train out to Cortelyou Road to witness it tonight at 9pm.

Tu Bishvat Seder this week in our Windsor Terrace branch of the School for Creative Judaism

Dear friends,

A happy story is set to reach its climax tonight in my neighborhood in Brooklyn. You’re all invited, and it’s worth accepting and taking the Q train out to Cortelyou Road to witness it tonight at 9pm.

It started, like many stories begin these days, with anger and accusations of hate, followed by cancellations. But then, right as everyone was taking sides and feeling hurt and commenting and grieving how rotten the world has become, there was an unexpected twist in the plot. It was so radical that it disarmed all the nay sayers and confused all the yay sayers and reshuffled the deck to shake it out of the political, and into that distant realm we used to occasionally inhabit called “human.”

The story began when a Palestinian restaurant opened a couple months ago. The owner, Abdul Elenani, an Egyptian married to a Palestinian woman, named the restaurant after his beloved, Ayat. There were several bold decisions made by the owners. When you walk in the first thing you see is a large mural of Al Aqsa. Around it are images of beauty, and oppression. When you open the menu the first thing you see is a full page in Arabic, Hebrew and English that reads: “End the Occupation.” All of that did not cause a stir. What did was the seafood section. It reads: “From the River to the Sea: Shrimp Kebab, Salmon Kebab, Whole Red Snapper, Whole Branzino.”

Within a few weeks from opening, Abdul had received dozens of hate mail, death threats and suggestions for what should happen to the dead and living of the Gaza strip. Soon after, newspapers began reporting about it. Some Jews in this incredibly diverse neighborhood swore it off, while others started organizing a boycott.

And then Abdul miraculously transformed the direction of the story. There were also Jews who came to the restaurant to show solidarity in the face of the boycott. In conversations with them he managed to come up with a plan: he invited them, and the entire Jewish community of the neighborhood to a Shabbat dinner. Word started trickling out. I caught word of it on the Whatsapp group of Israeli peace activists in New York, after one of the members received a warm invitation from Abdul, telling him to bring all his Israeli friends. “Everyone is welcome.” Under current circumstances Palestinians inviting Israelis, no matter how left wing they are, is almost unheard of. Abdul made it clear that the dinner will be free. He hired musicians to make the event festive. And Kosher caterers to allow for all Jewish diets to attend.

When we started realizing how big this event is becoming, some of the Israelis organized a second dinner, for the activists, who wanted to pay for their dinner. Abdul tried to convince us not to pay, but eventually agreed for people to pay whatever they felt comfortable paying. This past Monday 50 Israelis gathered at Ayat for dinner. It was a rare moment for a community of dispersed and argumentative peace activists - as marginalized as anyone these days - to come together and share a happy moment. Many of us will be there tonight again.

The title of the seafood section remains the same. But the understanding of the phrase, when sitting in the restaurant (which has a few other branches around the city) is different. This was the brilliance of Abdul. He told the NY Post: “You can’t come to me and translate my verse. You should ask me and I will give you my translation. I’m not going to change it because you want to change the meaning to feed your story.”

What does it mean to him? “This mantra stands for Palestinians to have equal rights and freedoms in their own country. In no way does this advocate any kind of violence.”

Personally, I’ve heard this mantra many times in my life. I don’t like it when Palestinians use it, or when Jews use it. But there was one time when for a moment it sounded just right, when my friend, activist and writer Udi Aloni roared it at a protest: “From the river to the sea ALL the people will be free!”

I am of course aware of the problematic nature of this phrase, and of the erasure it implies in the minds of many people who employ it. But the simplicity, even the innocence that it can hold when spoken by some, helps me in those cases to remove the armor, the tinted glasses, and whatever is on my ears skewing the sound bites, and see a human being. This is what can save us. This is redemption.

If one man can take a cancellation circus and transform it into a celebration of humanity, maybe a lot more of the horrors we are witnessing are also opportunities for transformation.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Wonder, Mindlessness and A Love Supreme

by Rabbi Misha

Creation is the move from chaos to order that is often obscured by darkness. Like most things in this universe, we can’t see it happening. It’s like the communication between trees, the realization reached by the person next to us on the subway, or the perfect, disjointed unison of a Jazz quartet.

John Coltrane - A Love Supreme, Part IV - Psalm (Live In Seattle, 1965)

Dear friends,

Creation is the move from chaos to order that is often obscured by darkness. Like most things in this universe, we can’t see it happening. It’s like the communication between trees, the realization reached by the person next to us on the subway, or the perfect, disjointed unison of a Jazz quartet.

“I never have to tell them anything,” said John Coltrane of his three collaborators, McCoy Tyner, Jimmy Garrison and Elvin Jones shortly after they completed one of the greatest Jazz albums in history, A Love Supreme. “They always know what they’re supposed to do and are constantly inspired. I know that I can always count on them. And that gives me confidence. There is a perfect musical communion between us that doesn’t take human values into account.”

So goes creation. No human values. A logic far deeper is at play when, for example a seed sprouts in the earth.

“Even in the case of A Love Supreme," continued Coltrane, "without discussion, I don’t go any further than to set the layout of the work.“

Not to compare a professed servant of God to God, but it seems that Coltrane followed in the image of the divine, as described in Genesis:

“And the earth was formless and empty

and darkness was over the surface of the deep,

and the spirit of God was hovering over the waters.

And God said ‘Let there be light,’

and there was light.”

The holy phrase תהו ובהו, translated above as “formless and empty” is worth pausing over in this musical context. While the phrase is not exactly logical, more linguistic or poetic, possibly even onomatopoeiac, תהו comes from תהה meaning to wonder, and בהו from בהה meaning to mindlessly stare, or zone out. The chaotic raw materials of creation are mindfulness and mindlessness. These are often the two elements that lead to something new. The wondering, a type of thinking that implies curiosity and inquiry is the active element. And the blank staring is a type of passive emptiness without which, in my own experience new ideas don’t come. We need both the search and the rest, the waking and the sleep for newness to appear.

Consider this statement from Coltrane: “For me, when I go from a calm moment to extreme tension, it’s only the emotional factors that drive me, to the exclusion of all musical considerations.”

What rises in him while he’s blowing his horn is divorced from the musical structure of the piece. The moment of creation, as we might call it, when a musician is truly connected, and allows their instrument to be a vessel of the soul, is a moment of chaos and freedom, which can only come about within the structure held by the other members of the ensemble. While he’s in תהו, wonder, the rest of the quartet is in בהו, mindlessness. When they hold the wonder - he can inhabit the emptiness.

With the frame of melody, chord progression and improvisation, Jazz combines structure and freedom, intention and emptiness, prayer and meditation. This is especially true of the Spiritual Jazz out of which was born A Love Supreme, a blast of inspiration shot into the world in 1964, from a musician who called music his “way of giving Thanks to God.”

Tonight we will be gathering at the National Jazz Museum in Harlem to experience the overlap between music and faith that drove Coltrane, through the Jewish Jazz of our musical guru Frank London, and his ensemble. I hope to see you there.

We see the chaos in the world. We tremble at its empty formlessness. What we cannot yet see is the new light being created out of it. Perhaps we will catch a glimpse of it this evening.

There is a structure to the universe. Some have heard it called a love supreme.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Hope resides in the Spirit - reflections on a David Shulman lecture

by Julia Stone

“What time is it right now in Israel?” David asks. He’s sitting next to Rabbi Misha in the front of the room- father and son- clad in earthy winter flannels and sweaters.

By Julia Stone

“What time is it right now in Israel?” David asks. He’s sitting next to Rabbi Misha in the front of the room- father and son- clad in earthy winter flannels and sweaters. It’s a Monday night and the two men are staring out at a crowd of about 70 Jewish New Yorkers, anxious in our folding chairs, all of us looking for some kind of lifeline. When David starts to speak, he’s so gentle it’s like he’s having 70 private conversations at once. He is effortlessly intimate.

“It’s the middle of the night in Israel”, someone answers. You can see David’s chest cave in slightly. “The nights are the worst”, he whispers like a confession, “the nights are filled with terror.”

David lives in Jerusalem, but he’s one of a group of devoted Israeli activists who have been traveling to the occupied West Bank for some 20-odd years to protect Palestinians from increasingly violent Israeli settlers. The activists wake up before dawn, travel through checkpoints, and decamp for the night in Palestinian homes – their physical bodies serving as the last line of defense.

I googled David before I arrived at the talk, and it’s difficult not to be immediately impressed by him. Or should I say enamored. He’s a multi-lingual, multi-award-winning scholar and Indologist, and he’s also a poet- although I’m not sure which language he writes in. Somehow, in the early 2000’s, he found time to join the nascent grassroots volunteer organization - Ta’ayush - that’s long since been at work to “break down the walls of racism and segregation by constructing a true Arab-Jewish partnership.” It strikes me that David is many things inside of one human vessel.

***

Reporting about the October 7 Hamas attack and what’s happening in Gaza has dominated the Western media in the past two months, but the West Bank is also under attack. Right now, amidst the devastation and chaos of war, a segment of Israeli settlers has seized the moment to further its goal of eliminating Palestinians from the southernmost part of the West Bank- and they’re doing so with the tacit approval- and sometimes even direct support- of the Israeli Defense Forces.

The settlers launch their intrusions into the Palestinian homes at all hours, but they particularly favor the middle of the night. They know to strike in the darkness- when the cameras of the Israeli activists struggle to capture what’s happening in the shadows. When the Palestinian children are asleep. Aren’t we all the most vulnerable while dreaming?

But David lets us watch the sunrise with him as he begins his talk. He paints the sky over the Palestinian homes- golden, warm, the glow transforming throughout the day like onions turning to caramel. He describes a village of shepherds. These aren’t political extremists- these aren’t individuals affiliated with the various Palestinian terrorist groups that dominate the news headlines. These are people who plow the land. Their livelihoods depend on the fruits of the soil.

Under the Oslo Accords, the West Bank was divided into three areas: A, B, and C – noncontiguous sections of land where an estimated 3 million Palestinians currently reside. David’s group of activists primarily focuses on advocating for Palestinians in Area C. “Let’s imagine a village”, he begins, “in the South Hebron Hills- the southernmost part of the occupied West Bank.”

The land here is inhabited by shepherds and small-scale farmers, or a combination of the two. David tells us that they are not nomadic people, but are firmly rooted and many of them have worked this very land “since time immemorial.” They are ordinary, peaceful human beings with an “almost-blank” security record. They live a “biblical lifestyle” in small hamlets, where their homes consist of 4-7 canvas tents, maybe a few metal shacks. As David speaks, it is increasingly clear that these people are a threat to no one.

It is ravishingly beautiful there, he tells us. There are sheep and goats and the hills are rocky and elevated and speckled with green, thorny shrubs against the backdrop of beige. In the spring there are wildflowers. There’s a vista and you can gaze out for miles as the land and the sky change color in tandem throughout the day-- wrapping-up in a blanket of deep purple blue. David tells us that the sight of the shepherds never ceases to move him.

***

About half a million Israelis currently live in the West Bank, which under international law is completely illegal. Under Israeli law, however, the older settlements are still regarded as legal. But the same can’t be said for the new outposts.

There are three primary types of Israeli settlements, and David outlines important distinctions among them. First, you have the “quality of life” settlements, built close to the 1967 border Green Line. The Israelis who live here don’t usually have a particular ideological attachment to the land, but instead typically settled there because it was cheap. Israelis could build a big villa there with the help of government subsidies, and most of them commute to the larger Israeli cities for work.

The residents of these settlements don’t tend to be violent, although some, like the settlers in Halamish in the hills north of Ramallah, have from the start having been “making life hell” for the Palestinian villagers of Nabi Saleh. These settlers constantly harass, attack, and steal land from the villagers, and they even took over the beautiful well that was a central site and vital component of life in Nabi Saleh. Three Israelis were also killed Halamish in a stabbing attack in 2017, which only increased the tensions.

The second type of settlements are the “veteran” settlements placed in the heart of the West Bank; these residents are ideologically committed. These are the Jews who believe they have a religious commandment to settle the land, and most of these settlements were established in the 1980’s and 90’s. The settlers who live there are virulent and impassioned, with the settlers of Itamar southeast of Nablus representing some of the most violent among them.

The third type of settlements – and easily the most terrifying- are the “outposts.” David tells us that outposts are a relatively new tactic of the most radical settlers- and they’ve only been established over the past five or six years. But he estimates that there are already about 100 outposts.

The outposts are where the most aggressive settlers- often teenage boys- come to claim their turf. They bring with them sheep and goats and M16s. David describes these boys as frequently “deeply troubled, brainwashed teens” who have found a type of asylum within the settler movement. They embody a certain form of religiosity that isn’t unlike other religious extremist groups. And they are a perversion of every Jewish value that I hold dear.

Most importantly, perhaps, these outpost settlers are completely safe from any consequences of their actions. They think they’re going to bring the Messiah by clearing the land of any non-Jews, or more secular Jews like me, and they’re in favor of an apocalyptic war. To them, the Palestinian farmers and shepherds are the ones defiling the land.

***

And here’s where David begins to tell us about how, exactly, these settlers go about ridding the land of the Palestinians. It’s important to note several things about David- highlighted both by his son Misha and his daughter-in-law Erika who had gone with him on some of his protective missions into the West Bank.

David isn’t a person who complains much. He was born in the United States but he chose to move to Israel in 1967 after a self-proclaimed love affair with the Hebrew language-- but his life work has involved the study of Indian languages and cultures. He served in the IDF and raised his three sons in Israel, where they also served. David doesn’t consider himself to be on the far-left. He thinks that any moderate person would feel the way about the settlers that he does - if only they could see them in action, face-to-face.

David has regularly made the uncomfortable and dangerous journey to the southern edge of the West Bank for over 20 years. He’s no stranger to the area, and he has no reason to exaggerate or lie about anything that he’s about to tell us. Listening to him, you quickly understand that he sees this particular slice of land, with these particular inhabitants and intruders, with a sense of indisputable moral clarity.

It’s also clear that David understands the full gravity of his descriptions and language. He tells us about how his beloved grandmother, who lived in the Western Ukrainian city of Mykolaiv was subject to a devastating Cossack pogrom. He describes how his grandmother’s brother nearly escaped the violent onslaught by taking refuge in a pool of water nearby, but instead he drowned to death while hiding. David doesn’t take the word “pogrom” lightly.

And yet, that’s the word he uses to describe what some of the settlers are doing to the Palestinian villagers. David explains that he’s only going to share details from events that he’s seen with his own eyes. There’s too much disinformation and misinformation to believe almost anything else at this point. Bearing in-person witness to the violence is crucial.

The outpost settlers like to attack between midnight and 3am. They arrive in groups ranging from 3 to about 50, but typically there are around 20 of them. Every single one of them is armed. David mentions here that the Israeli Minister of National Security, Itamar Ben-Gvir, has been instrumental in ensuring that these settlers get plenty of M16s.

The settlers also carry pistols and butcher knives. Butcher knives. The attackers are sometimes young- about 16 or 17 years-old, but there are also older men in their twenties or thirties. They are rage-filled and destructive. David tells us that the settlers wear Israeli army uniforms- but they are not soldiers. They are pretend soldiers.

These teens are not trained to use weapons, but that doesn’t seem to faze Ben-Gvir. They go house to house and start shooting- sometimes into the air, but often aiming at sheep and goats- killing anything in their way. David tells us that he personally knows of about 10 people who have been murdered by settlers on these rampages over the last few weeks, but nothing ever happens to the killers. Israeli law has no purchase here.

And often the IDF soldiers actively support the settlers as they launch their midnight pogroms. The attackers “break anything that is break-able- doors, windows, cooking vessels…they might set fire to the house.” They are screaming curses and threats- “a mantra of threats.” They tell the Palestinian families that they “have 24 hours to leave” or else they will all be killed. Women, children, whoever.

If there’s any food in the homes, the settlers will throw it all out, maybe piss on it. Over the years, David’s group and other activists have helped the Palestinians secure water tanks on their property- essential infrastructure in such arid land. And the activists have worked to secure wind turbines and solar panels so that the Palestinians have electricity. But the settlers use these goods for target practice.

As they’re ransacking the locals, the outpost settlers shoot the turbines and solar panels and water tanks. They could be there from anywhere between half an hour to 3 hours, wreaking havoc upon the inhabitants. Sometimes these attacks will be coordinated with the IDF and other times the soldiers will just stand-by passively and watch it.

The Palestinians under attack are a far cry from the militant gunmen who invaded southern Israel. These Palestinians are not affiliated with terrorist groups. They have no weapons to defend themselves. They still use plows pulled by donkeys. If they can’t take care of the land, next year’s crop will be ruined. They won’t be able to survive.

David reminds us here that the entirety of the West Bank belongs to Palestinians- noting only one exception of the Etzion bloc- a bit of land purchased by Jews pre-1948. “Everything else is theirs”, he says. The settlements are built mainly upon so-called “state lands” meant to be kept in reserve for the Palestinian population; instead, they have been appropriated, through a legal ruse that the Israeli courts have accepted, for settling Jews on them, in clear contravention of international law.

Listening to him, you can tell that David is personally attached to many individuals that he’s come to know through his years in the West Bank. He doesn’t talk about Gaza- it’s too big, a live-wire, complicated by a different imbalance of power and grievances. Instead, he describes how some Israelis are at war in what are clearly the wrong places, adopting what are clearly immoral methods.

In the Southern Hebron Hills where he and the activists go to sleep, David uses his body as a shield. The Hebrew word “Magan” can mean a shield, a protector, or a source of peace in times of great trial.

David tells us about how the settlers and IDF soldiers take the plows that belong to the shepherds. Sometimes the soldiers even take the tractors. They confiscate the goods- knowing that they are essential to the Palestinians’ survival- and hold them in an army outpost somewhere. If the Palestinians or activists manage to track down the equipment, they are often charged 4-10 thousand shekels for their retrieval- an insurmountable amount for the shepherds and farmers.

These Palestinians are “living in terror”. They have zero rights and no recourse. They are frequently prohibited from accessing the land they own for their livestock to graze, and David tells us that with “lands in dispute” the Palestinians are at the mercy of a ruthless, bureaucratic machine.

***

Someone in the audience asks, “When the settlers launch their attacks and encounter you and your fellow activists, what do you do then?”

David answers that he speaks directly to the settlers who are attacking. He tells them that “what they are doing is illegal”- that the Israeli Supreme Court ruled in 2004 that Israelis cannot prevent Palestinians from accessing their own grazing lands. He feels it’s his job to inform them of their transgression- and if they don’t absorb the meaning of it in the moment, that maybe at some time later what he says might resonate.

The activists have also learned to stream the violence on Facebook Live, so the video can be shared even if their recording devices get destroyed.

But the activists are committed to non-violence, so their only weapons are the unenforced Israeli law, live videos, and the presence of their bodies. David concedes that all of the activists have been brutally attacked over the years. And the risk to their own lives only seems to be increasing.

The settlers see the war in Gaza as their moment of opportunity. David tells us that the Palestinians are being constantly harassed, and over the past six months Palestinians have been expelled from over 16 villages – highlighting how many Palestinians were forced out of Ein Samia village earlier this spring. With all eyes on Gaza, who will stop these violent marauders who violate the most fundamental principles of decency and humanity?

It is clearly not right that activists like David need to take their own lives in their hands to protect people who should never be under attack in the first place. There are enough actual enemies in this neighborhood to fight. As David finishes up his talk, one of the audience members asks him what we can do- how do we help? David admits that in the crush of war, there’s not much anyone can do- that he’s only doing the most micro thing and even that he says is not enough.

But in a world of big ideas and grand deception, the micro actions take on even greater meaning. The personal interactions between his group and the Palestinians they attempt to protect. The talk delivered to 70 strangers who are suddenly closer because of the shared experience of listening.

Someone asks David if he is an optimist. He replies that he’s not really an optimist- an optimist would have to look at what’s happening and rationally say that it’s going to get better. He thinks it might get better, but he doesn’t know for sure. Instead, he says that he still has hope. “Hope resides in the spirit” he tells us.

***

I hesitate to write about Israel as an American Jew, and especially as there’s a war going on that I’m not fighting. I don’t agree with the policies of the Israeli government, or many governments for that matter. I despise extremism in any form- be it the zeal of violent Jewish religious settlers or the leadership of Hamas.

But if David is brave enough to put his life on the line to protect his neighbors, the least I can do is to share his teachings. If I cannot prevent injustice, at least I can help keep injustice visible.

Listening to David speak, I’m reminded of the shaken feeling I had when learning about the Israeli peace activist Vivian Silver, who died at the hands of Hamas. Was she naïve to believe that the people she wanted to coexist with would also accept living side-by-side with her? Was her effort to befriend and support Palestinians all in vain?

And then I watched a clip of one of Vivian’s Palestinian friends, weeping on live TV. The news anchor was also weeping. What made Vivian a righteous woman has everything to do with her life and nothing to do with her death. Vivian might not have chosen how to be killed but she fully decided how to live.

Rabbi Misha wrote that his father, David, is perhaps most at peace right now while sleeping in the homes of Palestinians in the West Bank. Doing something, doing nothing. Existing there, side by side. His body, both a weapon of protest and a shield of justice. His spirit above them, preparing for a new dawn.

***

Out of the Depths

by Rabbi Misha

To mark 100 days of the hostages in captivity, and 100 days of death and destruction, as a means of praying for an immediate ceasefire, an end to the displacement, destruction and killing of innocents, and a safe return of the hostages, I turn to the ancient words of the poet:

Gaza, as seen from Kfar Aza. Photo by Itamar Dotan Katz

Dear friends,

Dear friends,

To mark 100 days of the hostages in captivity, and 100 days of death and destruction, as a means of praying for an immediate ceasefire, an end to the displacement, destruction and killing of innocents, and a safe return of the hostages, I turn to the ancient words of the poet:

מִמַּעֲמַקִּים קְרָאתִיךָ יהוה

Out of the depths I call to You

Two great minds help me make meaning of these words and those that follow in Psalm 130. 19th century German rabbi, Samson Rafael Hirsch, and contemporary (Jewish) Zen priest and translator of the Psalms, Norman Fischer. This psalm, writes Rabbi Hirsch “sings of the ways in which the Jewish spirit can rise up even from the depth of that deepest misery of all, misfortune coupled with the burden of guilt.”

This is our situation, after being brutally attacked, and having responded with an operation that took the lives of at least 23,357 people.

The poet continues:

אֲדֹנָי שִׁמְעָה בְקוֹלִי תִּהְיֶינָה אָזְנֶיךָ קַשֻּׁבוֹת לְקוֹל תַּחֲנוּנָי:

Listen to my voice

Be attentive to my supplicating voice

קוֹל תַּחֲנוּנָי, “My supplicating voice,” is not only about begging according to Hirsch. Coming from the Hebrew word חן, grace, it is the expression of a broken person’s commitment to improve: “I endeavor to make myself worthy of Your grace once more,” he translates. God hears our prayers when they are not complaints. The cries of help heard by divine ears are those in which despite our misery and despair we leave an opening to the possibility of human agency and goodness.

אִם עֲוֺנוֹת תִּשְׁמָר יָהּ אֲדֹנָי מִי יַעֲמֹד: כִּי עִמְּךָ הַסְּלִיחָה לְמַעַן תִּוָּרֵא

If you tallied errors

Who would survive the count?

But you forgive, you forbear everything

And this is the wonder and the dread

The dread is related to what Hirsch calls “the iron law of cause and effect.” We know what killing thousands children will do as well as Hamas knew what killing, kidnapping and raping brings. It should fill us with dread to the brim. But the wonder is there too in the form of the unknown, of the possibility of transformation, of the very real existence of changing one’s ways. In Hirsch’s words: “You have provided man, Your creature who is capable of sin, with the ability to rise up again at any time, and assured him of Your help and forgiveness in his striving for redemption from the bondage of sin.” There is both wonder and dread in the idea of forgiveness, in which in Hirsch’s understanding the past is wiped out, and instead we might experience “a new future, untouched by all the consequences of previous error.”

קִוִּיתִי יהוה קִוְּתָה נַפְשִׁי וְלִדְבָרוֹ הוֹחָלְתִּי: נַפְשִׁי לַאדֹנָי מִשֹּׁמְרִים לַבֹּקֶר שֹׁמְרִים לַבֹּקֶר

You are my heart’s hope, my daily hope

And my ears long to hear your words

My heart waits quiet in hope for you

More than they who watch for sunrise

Hope for a new morning

“Together with the awareness of my guilt,” Hirsch explains, “there is also the hope and trust in forgiveness.” It is hard to see forgiveness now, but we know it exists, and can appear unexpectedly as it has done countless times in each of our lives. “Even in the low state to which I have descended through my own fault, within the inalienable core of my soul there lies the force that will draw me up... a force which, in the midst of the night of my own life and from the darkness of the nights of time, will help me find the light that heralds its approaching nearness. And my own trust in the morning to be brought to pass by the coming of forgiveness is greater and surer still than that of the eye which looks eastward at night to watch for the morning.”

יַחֵל יִשְׂרָאֵל אֶל יהוה כִּי עִם יהוה הַחֶסֶד וְהַרְבֵּה עִמּוֹ פְדוּת: וְהוּא יִפְדֶּה אֶת יִשְׂרָאֵל מִכֹּל עֲוֺנֹתָיו

Let those who question and struggle

Wait quiet like this for you

For with you there is durable kindess

And wholeness in abundance

And you will loose all our bindings

Surely

The word "Yisrael" means those who question and struggle. What allows us strugglers to find peace even in our darkest, most guilt-ridden hours is the knowledge that love is ever-available. Or in Hirsch’s words: “Loving-kindness is ready at all times to redeem.”

Here's Fischer's full translation:

Out of the depths I call to You

Listen to my voice

Be attentive to my supplicating voice

If you tallied errors

Who would survive the count?

But you forgive, you forbear everything

And this is the wonder and the dread

You are my heart’s hope, my daily hope

And my ears long to hear your words

My heart waits quiet in hope for you

More than they who watch for sunrise

Hope for a new morning

Let those who question and struggle

Wait quiet like this for you

For with you there is durable kindess

And wholeness in abundance

And you will loose all our bindings

Surely

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Dying With A Kiss

by Rabbi Misha

Moses died differently. So did Miriam and Aaron, as well as Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. These six all died, according to the Talmud, with a kiss from the shechinah, the gentle presence of God.

Dear friends,

Moses died differently. So did Miriam and Aaron, as well as Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. These six all died, according to the Talmud, with a kiss from the shechinah, the gentle presence of God. Some of us are lucky enough to receive a soft departure, and some less. Dying, I learned this week can, under some circumstances, be a beautiful part of life.

Last Shabbat’s Parashah was Vayechi, “And he lived,” which describes Jacob’s death. The patriarch gathers his children. He blesses his grandchildren. He leaves instructions for his burial. He speaks to each of his sons. Then he lays down and “is gathered to his people.”

This special way of describing death implies a type of reunion with previous generations, possibly with loved ones who have passed. It suggests that dying is an experience that is decidedly not solitary. The word the Torah uses for “people” is actually plural, עמיו, “peoples,” as if to say “when you die you will not be alone.”

The Jewish prayers often associated with death imply a presence that accompanies the dead.

Psalm 121, part of the canon of Psalms in funerals and burials, puts it this way:

יְהוָ֥ה שֹׁמְרֶ֑ךָ יְהוָ֥ה צִ֝לְּךָ֗ עַל־יַ֥ד יְמִינֶֽךָ׃

YHVH is your shomer, your guardian companion, the shadow by your side.

After Jacob breathes his last, we immediately hear about a kiss:

וַיִּפֹּ֥ל יוֹסֵ֖ף עַל־פְּנֵ֣י אָבִ֑יו וַיֵּ֥בְךְּ עָלָ֖יו וַיִּשַּׁק־לֽוֹ׃

“Joseph flung himself upon his father’s face and wept over him and kissed him.”

In our tradition, that kiss is expressed in a variety of physical and spiritual ways. People sit with the body from death until burial, often reciting Psalms. The body is washed and purified, while the washers recite love poetry from the Song of Songs. Some bodies get cleansed in the Mikvah. All of this comes out of a loving concern for the soul, which is imagined to still be present in the vicinity of the body until burial.

Finally, after family and friends express their love and appreciation, the body, now dressed in soft cloth, is laid to rest, and then lovingly covered with the earth from whence it came.

The tradition is signaling to us the importance of a death of beauty. Death is not separate from life, but an integral part of it, and for some it can be a truly wonderful part, if we treat it with the right attention and care.

As I spent the last week with a dear grandparent preparing to pass, I marveled at the sweetness of a blessed departure. Family gathered around her in her final days. She blessed them all and thanked them, and they her. Once she passed, her body received the full treatment that Jews offer their dead. It was as beautiful a death as one could hope for.

This week brought into sharp relief the the brutal deaths of so many Palestinians and Israelis over the last months, many of whom did not even receive proper burial, never mind the unspeakable moment of death itself. This never-ending war in Gaza has robbed so many people of their lives. And it has robbed almost all of those who lost their lives from a loving, dignified death as well.

Let this at least remind us of the glory of a dignified passing, and help us seek the sweetness and blessings in times of transition and loss.Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

Small Moral Acts

by Rabbi Misha

“Never underestimate the power of one small moral act.” This was one of the lines that stuck with me from my father’s talk about the West Bank on Monday.

For those of you who missed it, David Shulman's talk about the situation in the West Bank during the war.

Dear friends,

“Never underestimate the power of one small moral act.” This was one of the lines that stuck with me from my father’s talk about the West Bank on Monday. When contemplating this week’s parashah the following morning, I realized that this is a defining characteristic of Jewishness, or at least of the biblical character after whom Jews are named, Yehudah, or Judah.

The parashah begins with the greatest Hail Mary in the Bible. Joseph and his brothers have been estranged for decades, since they sold him into slavery. Now the brothers come in front of Joseph a second time to beg for food. Joseph responds by angrily imprisoning Benjamin and telling the rest of them to go back to Canaan. The relationship is on the verge of becoming irreparable. If they leave, Jacob will die of sorrow, and the brothers will forever live in animosity. It is at this moment that Judah steps into action. There is no reason for him to think that what he is about to do will help. Joseph has planted stolen goods on them and used it as proof to imprison Benjamin. He sits on his throne surrounded by advisors and guards. He has not shown openness to anything other than deciding things on his own.

However, Judah’s desperation seems to move him toward a simple, crazy act:

ויגש אליו יהודה

"And Judah approached him."

The early translators of Torah into Aramaic translate this: “And Judah came close to him.”

This act, which shouldn’t have helped, only endangering the brothers further, radically changes everything. After decades of separation, anger and guilt, this step toward him brings tears to Jospeh’s eyes, and completely shifts the relationship toward forgiveness and love.

On Tuesday evening I was invited to speak at a protest of Israelis for Peace in Columbus Circle calling for immediately returning the hostages, a bilateral ceasefire and the Netanyahu government to resign. There I described this moment in the Parashah as exactly like the political moment in Israel/Palestine. There are two options on the table: solidifying our mutual relationship of hatred, anger and guilt for another few generations, maybe for good, or attempting a small, Judean act of approach.

The Netanyahu government will not make such an approach. “Never, ever,” as my father put it on Monday. “He will fight it tooth and nail,” he said. Netanyahu’s entire political life has been designed to prevent a Palestinian state. The ethos of separation, expressed in the Joseph story by living for decades with no knowledge of each other’s lives, and on the ground with walls and fences, has failed. Crazy as it might sound to Israelis who are licking their wounds and whose distrust of Palestinians is higher than ever; and crazy as it might sound to Palestinians who are still dying every day, this, now is literally the pivotal moment.

After Judah’s approach, and his soft speaking in Joseph’s ear, Joseph sends out of the room everyone other than the brothers, and weeps loudly. He tells his brothers who he is, and they are so shocked that they move away from him. It’s then that Joseph makes a gesture like his older brother did.

גשו נא אלי

“Come close to me,” he says, and the Torah continues, “And they came close.”

“Don’t be angry at yourselves,” he tells them, and one can hear him speaking to himself too: don’t be angry, Joseph.

It is then that Joseph suggests an end to the physical separation as well:

“Come down to me from Canaan, do not stay standing where you are. Instead, sit in the Land of Goshen and be close to me.”

This is the first of nine mentions of The Land of Goshen in the Parashah. Goshen is a kind of suburb of Cairo. It’s strange to have that many mentions of it in such a short segment. It’s as if I’d tell you to come live in Hoboken, and just keep saying Hoboken over and over and over until you start thinking I’m trying to communicate something else. Goshen comes from the same root of the word Vayigash. It can be understood less as an actual place, and more of a state of mind: It is the place of coming close, the town of pivots, the city of approaches against all odds; the land of small moral acts.

May we inhabit this land this Shabbat. May we fill the world with our small acts. May the Jews act like Judah did in front of Joseph. May the Land of Israel; of battling with humans and gods, become a land of Goshen, where massive acts of cruelty are replaced with small acts of kindness.

Happy Christmas to all of you who celebrate the birth of this true pacifist. And happy Solstice: the darkest days are behind us.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

The Pain of Inflicting Pain

by Rabbi Misha

At our Shabbat/Hanukkah concert last week I described how my father has been making us all nervous by insisting on spending some nights in Palestinian villages in the West Bank that are threatened by extremist Jewish settlers.

Grayson expressing darkness through movement at our Windsor Terrace branch.

Dear friends,

At our Shabbat/Hanukkah concert last week I described how my father has been making us all nervous by insisting on spending some nights in Palestinian villages in the West Bank that are threatened by extremist Jewish settlers. He has been working with Ta’ayush: Jewish Arab Partnership for Peace for decades to work against the settlers’ attempt to ethnically cleanse certain parts of Area C, which makes up much of the Palestinian Authority. Usually this involves simply being there, since a Jewish presence tends to restrain the settlers. As soon as the war began, the settlers upped their antics and as a result several of those villages were abandoned. The activists sprang into action and have been taking shifts sleeping in some of the villages to help them withstand settler violence. Spending time there is not without risk. And yet, during this war, the only times in which my father has been at peace were those nights spent taking a shift in one of the villages.

He doesn’t explain exactly why this sense of peace manifests there, but I suspect that it has to do with what might be called “doing the right thing.” It is a way for the activists to get beyond all of the complicated questions of justice, self-defense, nationality, and touch upon a simpler driving ethic: people should be allowed to live peacefully.

This war has created an internal rift in every Israeli, and in most Jews around the world as well. We want to live by this simpler ethic, and yet virtually all Jewish Israelis and most Jews world-wide support the war to uproot Hamas, which has thus far claimed the lives of 18,787 Gazans, most of whom were not Hamas fighters. Tens of thousands more have been wounded. Hundreds of thousands have lost their homes for good. Millions are traumatized, trying to survive moving from place to place, living in tents that can’t stop the rain, with little to no food or clean water. No matter our reasoning, no matter whose fault we think this is, no matter our position on the war, we are living with the knowledge that we are inflicting tremendous pain on the people of Gaza. We are living the agony of that deep dissonance between who we want to be and what we are doing. This has been the story of the State of Israel from day one.

Receiving pain is worse. But inflicting pain is also incredibly painful.

Israeli media is incredibly sparse on news about Gazans. One of the reasons for this is that it is too painful to them to take that information in. They’re still processing the trauma of October 7th, and everyone has friends or family in the army, and they keep having to run to the bomb shelter, so taking in the details of a massive civilian catastrophe is beyond their capacities.

When I was at synagogue in Jerusalem two weeks ago, the rabbi spoke about Jacob’s great fear before returning to the land of Israel to meet his brother Esau, whom he had wronged two decades earlier. The Torah tells us twice that Jacob was afraid: one, says Rashi, denotes his fear of being killed. The other his fear of killing. He’s equally terrified of receiving and of inflicting harm, perhaps because he knows that when you inflict harm you have two options: acknowledge what you’ve done and suffer through a painful Teshuvah, or, more likely, deny it and live a compromised, angrier life.

This anger, fueled by the denial of harm you caused is one of the final things Jacob speaks to before he dies. On his deathbed he addresses each of his children. When he comes to Shimon and Levi, we learn that of his entire life, the one thing Jacob is most ashamed of is his sons’ “honor killing” of the sons of Shechem, when the two brothers brutally murdered an entire village in response to their sister’s rape. When explaining Jacob’s words at his deathbed, Rashi ties that vengeful act with the terrible deed of selling their brother Joseph into slavery.

“Shimon and Levi are brothers,” says Jacob, and Rashi explains: “brothers in the plot against Shechem and against Joseph.”

Rashi’s suggestion is that Shimon and Levi’s role in getting rid of Joseph led them, through denial and escaping accountability to an anger that drove them to commit murder.

אָר֤וּר אַפָּם֙ כִּ֣י עָ֔ז וְעֶבְרָתָ֖ם כִּ֣י קָשָׁ֑תָה

"Cursed be their anger so fierce,

And their wrath so relentless,"

Says their dying father.

On Monday evening my father will be giving a talk in New York about the situation in the West Bank, and the work of Israeli-Palestinian activist groups like Ta’ayush there. You’re all invited, sign up HERE. His work there is the work of seeing with your own eyes the suffering inflicted by Jews, and acting to prevent and repair it. It is the work of beginning to address the harm that Israel is causing to Palestinians, and to our aching Jewish hearts. If we stand a chance at making it all work over there, it might begin on Monday evening.

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Misha

A lion Has Roared

by Rabbi Misha

Norman Lear passed away this week after 101 years of working to bring light and love to this world. I had the good fortune to know Norman and have occasional conversations with him, often expanding on the first thing he ever told me: “We have to take religion back in this country.”

The interview I conducted last year with Norman Lear and his daughter Maggie in honor of his reception of the Kumah; Rise Up Award for a life in the intersection of faith, art and politics.

Dear friends,

Norman Lear passed away this week after 101 years of working to bring light and love to this world. I had the good fortune to know Norman and have occasional conversations with him, often expanding on the first thing he ever told me: “We have to take religion back in this country.” The last time we spoke he was trying to remember an old Yiddish lullaby he used to hear as a child. It felt as though he was stretching back in time to a point in his life when religion represented goodness and love, before it was taken away from him, from us, before it soured.

His death reminded me of the greater context in which this war is taking place. It is part and parcel of the battle over the soul of Jewishness, the spirit of faith, the underlying demands, purpose and meaning of this word human beings use sometimes, God.

On the first night of Hanukkah yesterday there were two events that portray opposing attitudes toward this question. In the Old City of Jerusalem, the Maccabees March was an ultra-nationalist display of religious superiority and hate. Religious Jews likened themselves to the freedom fighters of old as they took over the Muslim quarter in that delightful way of theirs.

When evening landed on New York a different type of Jewish gathering took place in Columbus Circle, where a few Jewish organizations partnered with Arab and Muslim friends to light candles for a ceasefire. They stressed solidarity and friendship that extends beyond the tribes. They asked people to display “ceasefire now” signs on their windows in the way that a Hannukkah Menorah is displayed on the window. In doing that, they likened themselves not to the Maccabees, but to the rabbis who molded Hanukkah into what it is today. Those rabbis, who lived a generation or two after the Maccabees made a conscious choice to change the focus of the holiday from military victory to light and miracles.

One of the reasons the rabbis chose to do that was because the Maccabees really were not all that different from the religious fundamentalists in our world today. The Book of Maccabees describes them at war with the moderate Jews, and with any expression of solidarity with the people of the world at large, even before the cruel Greek ruler, Antiochus came into the picture.

One fun activity is to take the Hanukkah story and suggest who in that story is the equivalent in today’s conflict. We could say that Netanyahu is Antiochus, the evil ruler who won’t allow the locals self-expression. That would put Hamas as the Maccabees, which despite the similarities doesn’t land right. We could say that Sinwar is Antiochus, refusing the Jews their right to exist as free people and the IDF are the Maccabees. But the power dynamic there seems way off.

Instead, I’d offer the following: The Jews in the story are those who are not free. Taken hostage by the forces of division and extremism, the moderate majority are being forced to act in ways that are antithetical to who they are. Hamas and the Israeli extreme right have swept over the land with their ideology of separation, which has led us to this point. The entire world seems teetering on the verge of being engulfed in this self-centered world view.

I believe the miracle will come. I believe the forces of dark division will be uprooted, or weakened enough that we will be able to rededicate our broken temple, to again live authentically within our vision of a shared humanity. But we will have to speak our vision loud and clear in order to succeed.